SOURCE: THE GUARDIAN

BY: IAN BLACK

Ben-Gurion Boulevard climbs from the bustling port on Haifa’s Mediterranean shore up Mount Carmel towards the famous Bahai shrine, its gleaming golden dome surrounded by lush terraced gardens. On the south side of the palm-lined road, on a spring lunchtime, the Fattoush restaurant is packed with customers chatting noisily in Arabic and Hebrew over Levantine and fusion salads, cardamom-flavoured coffee and exquisite Palestinian knafeh desserts.

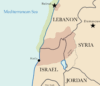

Fashionable eateries like Fattoush are one reason why Israel’s third largest city and its biggest “mixed” one, as officially classified, is held up as a model of Jewish-Arab coexistence. Not everyone agrees with the concept, of course, and the “c” word is often qualified, placed in inverted commas, or simply dismissed as propaganda. Official figures say Arabs make up 14% of Haifa’s 280,000-strong population; unofficial estimates are closer to 18%, swelled by students and commuters from nearby Galilee. Public spaces, at least, are open to all. And the ever-present Israeli-Palestinian conflict is, usually, softer-edged than elsewhere in the country.

“I prefer to talk of shared existence rather than coexistence,” says Yona Yahav, the veteran Jewish mayor. “Haifa’s Jews and Arabs are the same Jews and Arabs as in Jerusalem, but here things work in a stable way.”

Yahav’s office is lined with portraits of his predecessors, the first two wearing Ottoman tarbooshes. The street outside bears the name of one of them, Hassan Bey Shukri. Yahav flourishes a copy of a Hebrew newspaper notice mourning Shukri’s death in 1940. “I can promise you that this won’t happen if I die,” he jokes. He is also keen to point out that his secretary, Reem, is an Arab. “I can’t tell you that all Jews love Arabs and vice versa, but people do feel safe here.”

No one questions that the city is special. “If all of Israel and Palestine could be like Haifa, I’d be happy,” muses Amjad Iraqi, a twentysomething Palestinian intellectual. “It’s not lovey-dovey. Life is essentially segregated but every community accepts that you can do your own thing. It’s not perfect, but it’s still better than everywhere else.” Asaf Ron, who runs the municipally funded Beit Ha’Gefen cultural centre, argues that it is all about promoting empathy. “Many Israeli Jews don’t know any Arabs. We need to break down stereotyping and fear.”

Ayman Odeh, Israel’s most prominent Arab politician, lives in the Kababir neighbourhood, with its handsome mosque and stunning views over an azure sea. He also believes his home town is different. He served on the city council before being elected to the Knesset in 2015. “The situation between Jews and Arabs has always been better in Haifa than anywhere else in Israel, but it is far from equal,” he insists. “The mood is good and there is a sense of sanity. But it is not an island.”

The local HQ of Odeh’s party, the Democratic Front for Peace and Equality, is on Ben-Gurion Boulevard opposite Fattoush. It is ironic that the street is named after David Ben-Gurion, the Jewish state’s founder and first prime minister. But there are many similar examples: the Istiqlal (“Independence”) mosque is at the junction of Shavei Zion (“Returnees to Zion”) and Kibbutz Galuyot (“the Ingathering of the Exiles”) streets. Zionism Avenue snakes across the Carmel to the downtown Arab quarter of Wadi Nisnas.

Identity issues will be in the air in Haifa this month and next when Israel celebrates the 70th anniversary of its independence and Palestinians mourn the Nakba, or “catastrophe”, that the 1948 war represented for them. “Arabs don’t take part in Independence Day celebrations,” says Yahav. “They don’t feel it is their holiday.” Johnny Mansour, a historian from the Greek Catholic community, will be joining a “march of return” to some of the hundreds of Arab villages destroyed after the war – the same symbolic commemoration that has triggered the recent deadly upsurge of violence on the border between Israel and the Gaza Strip. Fattoush, proudly flaunting its Palestinian nationalist credentials, will be closed to mark the occasion.

1948: a fateful year

Haifa once represented modernity and progress but feels less dynamic these days. In the twilight years of the Ottoman empire it was the terminus for a branch line of the Damascus-Hejaz railway. Allenby Street is named for the British general who freed the town in 1918, soon after the Balfour declaration backed the establishment of a “Jewish national home” in Palestine. The port opened in 1933, followed by an oil pipeline starting in Iraq. At that time, explains historian Motti Golani, half the Jewish population spoke Arabic. During the second world war, when Italian aircraft bombed the city, Jews and Arabs huddled together in basements.

By 1948, the population was 70,000 Jews and 65,000 Arabs. But war changed that. In April, as fighting raged and the British prepared to leave, all but 3,000 Arabs were expelled or fled to Lebanon or the West Bank. The history of that fateful year remains bitterly contested: the Jewish mayor – unaware of military planning – urged Arab leaders to stay but they felt unable to comply with the terms for a truce. Newly arrived Jewish immigrants moved into abandoned homes in Wadi Salib. Many houses, defined as “absentee property”, are now in a state of advanced decline. The city’s flea market is held in the shadow of a crumbling Turkish bathhouse, Hammam al-Pasha. Impressive new glass and steel towers, housing the city’s courts, loom over the ruin

Haifa occupies an important place in Palestinian collective memory thanks to local luminaries such as Emile Habibi and Toufik Toubi. Habibi wrote the best-known novel by a Palestinian in Israel: The Secret Life of Saeed: The Pessoptimist. Etched on his grave are the words: “I remain in Haifa.” Acre-born Ghassan Kanafani, assassinated by the Mossad, captured the essence of the conflict in his novella Return to Haifa, in which a visiting Palestinian refugee encounters an Israeli woman who survived Auschwitz. Palmer Gate, the entrance to the port, is where Holocaust survivors came ashore and terrified Palestinians fled by boat to Acre or Beirut, mostly never to return.

‘Coexistence is not equality’

Emile’s shawarma restaurant – Haifa’s legendary best – is always crowded. Abu Shaker, near the port, serves superb hummus. Both are no-frills Arab-run establishments with large Hebrew signs outside and a majority of Jewish customers. But the city’s reputation for inter-communal harmony can be illustrated by even more impressive – if non-culinary – achievements: 32% of the doctors at the Rambam hospital are Arabs. Arabic is heard in Haifa’s shops and on its streets and buses in a way that it rarely is in West Jerusalem or Tel Aviv. The offices and clinics of Arab lawyers and dentists line the streets of overwhelmingly Jewish and upmarket residential areas. In other “mixed” Israeli cities like Jaffa, Ramle and Lod, Arabs are poorer and less socially mobile.

Hadar HaCarmel, up the hill from Wadi Salib, is Haifa’s most diverse neighbourhood. In its western quarter, 60% of the population is Arab. On Masada Street, a hipster cafe culture has blurred ethnic differences that are normally easy to spot. “Coexistence!” shrugs Arik, a Jewish antiques dealer. “In Haifa there’s no choice.” Yossi, who runs a nearby record shop, lives in Kababir; Walid, an Arab architect, in the largely Jewish area of Merkaz HaCarmel.

Haifa’s tolerance is tested at regular intervals. In October 2000, at the start of the second intifada, 13 Arab citizens were shot dead by police while demonstrating in solidarity with their kinfolk in the occupied West Bank and Gaza. Yahav’s predecessor ensured the city remained calm. It was harder three years later when a woman suicide bomber from Jenin blew herself up and killed 21 others in Maxim’s restaurant – jointly owned by Jews and Arabs. In the Lebanon war of 2006, a missile fired by Hezbollah killed two elderly Arabs. Successive Israeli wars against Hamas in Gaza – in 2008-9, 2012 and again in 2014 – saw anger flare. “In Haifa, Arabs and Jews live alongside each other, but when there is tension they move apart,” argues Amjad Shbita of Sikkuy, the Association for the Advancement of Civic Equality. “Haifa’s coexistence is the best in Israel, but it can still be easily damaged.”

Palestinians in Haifa and across Israel have grown closer to relatives and friends beyond the pre-1967 “green line” border with the West Bank, but their lives are very different and they have their own issues close to home. In 2013, protests erupted over a government plan to demolish the homes of“unrecognised” Bedouin communities in the Negev and build a Jewish town. Two years ago, after an unusually hot autumn, fires consumed large areas of the Carmel, triggering accusations by rightwing Jewish politicians of an “arson intifada” – though no one was ever charged.

Haifa-based NGOs have their work cut out tackling discrimination in social services and budget allocations. The worst poverty is in Halissa, a mainly Arab neighbourhood where violence is blamed on rivalry between Bedouin clans and relocated collaborators from the West Bank. “The Israeli idea of coexistence is about a majority and a minority – the strong and the weak,” observes Tom Mehager of Adalah (Justice), which is devoted to securing the rights of Israel’s Arab citizens – and has vocally condemned the army’s killing of Palestinians in Gaza. “Coexistence is not equality. Speaking the same language and eating hummus together doesn’t mean Jews and Arabs are equal.” Jafar Farah, who runs the Mossawa (Equality) centre, compares the relationship between the two peoples to one between “a rider and a horse”. And that, he insists, “is how Yona Yahav deals with the Arab community in Haifa.”

‘In Haifa it’s not hate, but not love either’

Education provides important insights. In Haifa, as elsewhere, Jewish and Arab children mostly attend separate schools. Many Arab children (the majority are Christians), study in fee-paying church schools, and a few dozen in Jewish ones. There are no Jews in Arab public schools, where standards are poor. The curricula are different too. “People want to stay within their own communities to speak in their native languages, have days off on their own holidays, and learn about their own history, culture and religion,” says Asaf Ron. “Assimilation through attending the other community’s schools is a free choice that almost no one chooses.”

The Yad beyad (“Hand in Hand”) private network of bilingual schools complains about long waiting lists and a struggle to secure municipal support. In its kindergarten in Hadar, Arab and Jewish six-year-olds sing songs and are captivated by nursery rhymes that interchange Hebrew and Arabic – a heartwarming but highly unusual sight. “The whole country is based on separation in a very profound way,” says Merav Ben-Nun, its community organiser.

Higher education is a different story. Haifa University is 40% Arab, and the Technion, the Israeli Institute of Technology, 23%, though Arab graduates are unlikely to find jobs in security-related industries. Arab students are younger than Jewish ones, who mostly spend up to three years from the age of 18 doing the compulsory military service from which the vast majority of Arabs are exempt. “Arab and Jewish students sit in the same classes but barely speak to each other,” notes Golani. National holidays – Holocaust Day, Memorial Day and Independence Day – feel especially awkward on campus.

Independence Day is celebrated in Haifa with concerts, folk-dancing and firework displays, but the highly polished jewel in the crown of the city’s coexistence narrative is the annual “Festival of Festivals”, held in December to mark Hanukah, Christmas and the Muslim holiday of Eid al-Adha. Tens of thousands of Jewish visitors throng the narrow streets of Wadi Nisnas, marvelling at the feeling that they have gone abroad for the weekend. Yahav is especially keen to promote the month-long event.

Older Palestinians tend to be relaxed about this, but younger activists can be contemptuous about condescension or racism towards “colourful” natives. Many are keen to assert their growing self-confidence in the face of what they condemn as Israeli “apartheid and settler colonialism” – in the words of a strategy paper that was drawn up in the cafe Fattoush last December.

The closure of Haifa’s Arab theatre, al-Midan (“The Square”), is cited as an example: state funding was withdrawn after it staged a play about a Palestinian security prisoner. The defiant response was to create an autonomous crowdfunded alternative – al-Khashabi (“The Stage”). Its Arabic-language performances are translated into English, but conspicuously not into Hebrew. “Independent Palestinian institutions do not believe in coexistence,” explains Al-Khashabi’s director, Bashar Murkus. “We believe in dialogue from a position of strength and independence.” His colleague Khoulood Tannous flatly refuses even to use the “c” word. “No one is shelling us here,” she adds. “It’s no Gaza, nor the West Bank. It’s mind games.”

Politician Ayman Odeh’s disapproving view is that influence should matter more than identity to Israel’s Palestinian minority, in Haifa and beyond, and that joint struggle is the key to a more equal future. “Arabs are developing autonomy at the expense of Arab-Jewish cooperation,” warns Sikkuy’s Shbita. Neither side harbours illusions about the other. “In Haifa it’s not hate, but there’s not too much love either,” is the stark conclusion of Omer Shaffer, a Jewish Technion postgraduate who was both moved and surprised when an Arab colleague told him to “take care” when he went off to do a stint of reserve army duty at a checkpoint in the West Bank. “It’s pretty indifferent. We’ve found a way to ignore each other without killing each other.”