The Unsung Heroes of the Titanic –"Abtaal Majhuuluun"

By: Leila Salloum Elias / Arab America Contributing Writer

For the Syrians who set sail on the Titanic, the promise of economic prosperity and a secure future lay beyond the Atlantic. Hailing from various villages, towns, and cities of what was then Syria, they held onto the hope that what lay ahead would offer something better. Economic improvement—that ubiquitous motivation for any immigrant to leave the land of their birth—was the same pull factor for the Syrian émigrés. For the majority who boarded, it was Amrika that beckoned. In April of 1912, the Titanic was meant to take them there.

Among these passengers were four newlywed couples. Four young men—three living in the United States and one in Canada—had returned to their hometowns in Syria to marry. For these newlyweds, the Titanic would serve as part of their honeymoon, or an extended one. They left Syria and traveled to Marseille, where they learned about the Titanic.

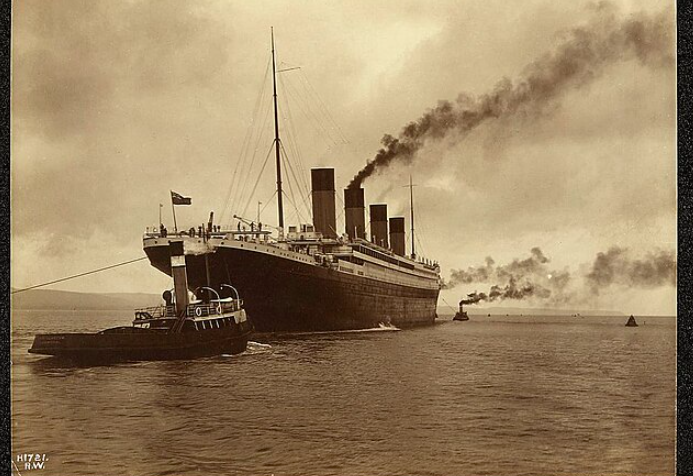

It had been billed as the most luxurious, largest, and finest steamer afloat—the queen of the ocean, the unsinkable Titanic. The couples took a train to Cherbourg, where they boarded the ship. This was the Titanic’s maiden voyage, and for the four brides, it would also be their first time crossing the waters of the Atlantic Ocean.

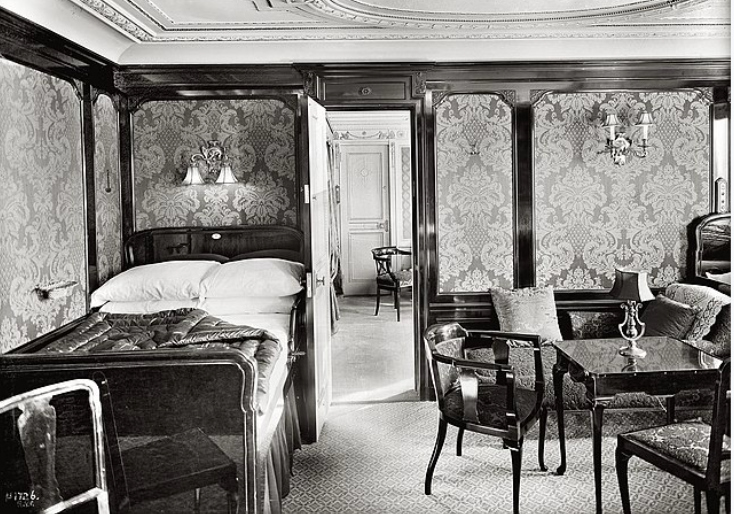

Niqula Khalil Naṣr Allah and Adal Ḥabib Ḥakim had married in Zahle, after Niqula returned to his hometown and was introduced to Adal. She was 14, and he was about 30. They were the only Syrians on board the ship traveling in second class.

Nicholas Nasser, his Americanized name, had established a successful wholesale confection and candy business in San Francisco. His uncles, Abraham and Albert, were already living there. They had immigrated earlier, around the turn of the century, and were known for establishing the first nickelodeon theater in the city. It was back to San Francisco that Niqula would be taking his young wife.

Niqula and Adal travelled to Brazil and then, as an extended honeymoon, took a tour of Europe before sailing to the U.S. The Titanic had not been their first choice, according to Niqula’s nephew, Philip. They had booked passage on another White Star ship but were told that the ship had ‘broken down’. Until today, the family contends that the White Star Lines most famous ship did not have all tickets for its maiden voyage sold. It was suggested then, to take the Titanic.

Two other newlywed couples were among the seventeen passengers from the village of Hardin. Anṭun Musa Yazbak and Silana Iskandar Abi Daghir had been married for just over a month. Antun, who had established a shoe repair business in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, had returned to his hometown in hopes of finding a wife.

His good friend in Wilkes-Barre, Jirjis Mubarik (George Moubarek), asked Antun for a favor. Upon hearing of Antun’s plans to return to Hardin, he requested that Antun accompany his wife, Amina, and their two sons, Jirjis and Halim, on the journey back to the United States. Amina had a sister, and it was suggested that Antun be introduced to her.

In Hardin, Antun met Silana, and according to the family, it was love at first sight. An engagement soon followed, and then the wedding. The five of them boarded the Titanic in steerage—Antun and Silana bound for Wilkes-Barre, and Amina with her two children heading to Houtzdale, Pennsylvania.

Butrus Sarkis Khalīl al-Khuri, a native of Hardin, had returned home after spending about five years in Wilkes-Barre, where he worked as a huckster. Just before boarding the Titanic, he married Zahiya Badr Khalil. The two had fallen in love, but financial hardship had delayed their wedding.

They decided to elope and join the group departing for the United States. However, Zahiya’s parents refused to let their daughter leave with Butrus without a proper religious wedding ceremony. That ceremony took place just hours before they set off with the others from Hardin.

Aboard ship, fellow Hardinites ensured the couple did not go without wedding festivities. In steerage, they celebrated the newlyweds’ marriage with traditional dabka and songs. It was their honeymoon, and they had the Syrian passengers there to celebrate with them.

From the village of Kfar Mishki came the newly married couple Karam Yusuf Karam and Mariya Ilyas. Karam was returning to his business in Gowganda, Canada, and traveling with them was Mariya’s father, Ilyas Yusuf Shahin.

Karam was a well-known individual in Ottawa’s Syrian community. He had returned to his hometown to marry the woman with whom he was in love. The Syrian community in Ottawa awaited their arrival ready to congratulate them on their marriage.

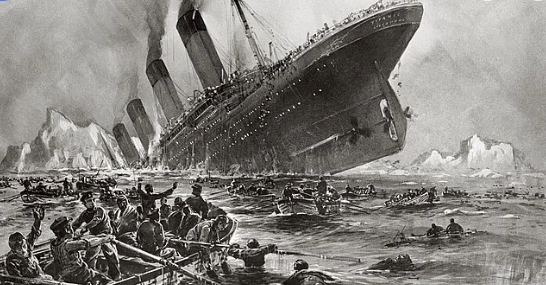

No newlywed Syrian couple survived. Of them, only two young brides would arrive in New York and disembark as, in the terms of many American newspapers, child brides, child wives or child widows.

For the Arabic newspapers and Syrian community, their grooms were the unsung heroes of the Titanic. In the face of death, they too, like the more widely recognized men who went down with the ship, upheld the law of the sea. They stood back and allowed women and children to board the lifeboats, just as their counterparts in first and second class had done.

Their heroism deserves to be remembered.

When the Carpathia arrived in New York on April 18th, American newspapers began reporting the survivors’ stories—many of which included the heartbreaking accounts of the two young widows, Silana Yazbak and Adal Nasrallah.

Their situation was described as dire: homeless in a foreign land, separated from their spouses for the first time, unable to speak English, and with no one to turn to but strangers who had known their husbands.

The cruel paradox was that the dream of a new beginning had ended in the nightmare of an unknown future, in an unfamiliar land, far from everything they had ever known.

Silana, a child widow, was described as a black-eyed beauty, her fingernails still stained with the red ink (henna) painted on her wedding night in keeping with Syrian custom.

It wasn’t just her striking appearance that drew the attention of reporters—it was the quiet, heartbreaking hope she held onto. Despite the tragedy, this young bride, now a widow, believed her husband might still be alive, perhaps aboard another rescue ship.

She didn’t want to accept the loss of the man she had just married, the man she loved. After all, the last words she had heard from him were: “I’ll be following you shortly. Don’t be afraid.”

As for Adal Nasrallah, American newspapers described her as a young and pretty Syrian girl—brokenhearted and a forlorn victim of fate.

The New York Times on April 19, 1912, reported that her husband was bringing her to live with some of his cousins in the United States. But now, the addresses were lost, and “Mrs. Nussa” (sic), the paper noted, “doesn’t know where to go” (8).

The following day, on April 20, 1912, The Denver Post called her the “most pathetic bride widow”—married for only a few short weeks (1).

Adal was taken to a hospital in New York for rest and recovery, but her grief only deepened. On April 20th, the New York Times reported that the distraught young widow, Adal, was being solaced by a Syrian priest and that the little Syrian bride of six months whose husband had died in the sinking was pitiably in need of comfort (7).

After placing her on a lifeboat, the last word she heard from him was simply: “Goodbye.” She clung to the hope that he had been rescued by another ship.

Arabic newspapers in New York mourned the tragedy and the loss of hundreds of lives claimed by the dark waters of the Atlantic. They reported on the deaths of the rich and famous—Astor, Stead, Hays, Guggenheim, and Strauss—as well as the heroics of the men who sacrificed their lives for others.

But among these men of honor, readers were reminded of their own Syrian brethren—men who, like the others, surrendered their lives to ensure the survival of others. In Arabic, the community read about the courage of these men and their gallant efforts to save those around them. They, too, were heroes.

On May 10th, al-Bashir reminded readers that it was not only the British and American male passengers, as reported in the American newspapers, who had stood back to allow women and children into the lifeboats—but also the Syrian men (2). They met death with the same chivalry and courage.

While British and American newspapers proudly lauded their own citizens, the Syrian community had every right to carry the same pride. Their men, too, went to their deaths for the sake of others. One example of this bravery was Antun Yazbak. His wife, Silana, spoke of how he, along with the other Syrian men, gallantly helped women and children put on their life belts and led them to the upper deck.

Antun and his wife were asleep in steerage when they were suddenly awakened by a violent bump. Instantly, Antun knew something was wrong. He quickly grabbed one of Silana’s nephews and handed her the other, then called for his sister-in-law to follow him.

On deck, an officer placed Amina into a lifeboat that was about to be launched. Antun handed her the child he was carrying, then placed Silana and the other boy into the boat as well. A frightened, shivering Silana clung to his hand and begged him not to send her away alone. There was room in the lifeboat, so he stepped in beside her, sat down, and put his arm around her.

But an officer approached, drew a pistol, and ordered him out of the lifeboat. Without hesitation and without argument, Antun complied. As he stepped away, his widow recalled his final words to her from the deck: “I’ll be following you shortly. Don’t be afraid.”

When Niqula Nasrallah placed his wife, Adal, into the lifeboat, she refused to go without him. Crying and hysterical, she pleaded with him to stay—there was, after all, a seat beside her. But he did not board. He made no attempt to jump in as the lifeboat was lowered.

Instead, survivors later recounted how Niqula leapt into the icy water, trying to save as many children as he could, guiding them toward the lifeboats.

When Adal was able to meet his California family years later, she spoke of Niqula’s courage and tenacity to fight death until the end and his efforts to help others survive. On February 16, 1913, the Pensacola Journal reported that “Nasrallah went to his death as uncomplainingly as did Smith or Astor or Marvin” knowing that “when he was gone there would be no one to care for her – his beloved Adele” (12).

According to both oral testimonies and written correspondence with families in Hardin, survivors recounted the poignant story of Butrus and Zahiya—inseparable from the very beginning until the end.

Despite Butrus’s repeated efforts to convince his bride to board a lifeboat, she refused to leave him. She was forcibly placed in the lifeboat, but each time, she jumped back onto the deck, unwilling to be saved without him.

In the end, the two were last seen on deck, locked in an embrace, choosing to meet death together. They died in each other’s arms.

As for Karam Yusuf Karam and Mariya Ilyas, both Kfar Mishki and the Syrian community in Ottawa mourned their loss deeply. The newlyweds, still on their honeymoon, had boarded the Titanic with others from their village. On April 24, 1912, the Quebec Daily Telegraph reported the death of “Joseph Kareem” under the headline “Syrian Man and Bride Victim.” The article noted that this prosperous merchant of Gowganda had returned to his birthplace, Kfar Mishki, to marry Maria Elias, and aptly described their ill-fated voyage as “their honeymoon and their passage to eternity” (1).

It was Zad Nasrallah (Marian Assaf), the sole survivor among the twelve passengers from Kfar Mishki, who would later confirm the death of the young couple.

Assaf’s account of the sinking, reported in American and Canadian newspapers, confirmed that not all the women who wanted to get into a lifeboat were rescued, explaining that three of her cousins had pleaded for a seat but were refused. These three women included the young bride Mariya Elias. It was also Marian Assaf who confirmed that when the gates were finally opened for steerage to reach the upper deck, in the rush to reach a lifeboat, many were shot dead by officers of the ship.

It was the eyewitness accounts from Syrian survivors and their letters sent back home to their families that provided the stories of the last hours of many of these passengers on the Titanic. We learn that there were those who knelt in prayer as they succumbed to the fate that lay ahead. Others held hands in a line of dabka as one Syrian passenger, al-Amir Faris Shihab, strummed his ‘ud to the song “shiddu al-himmah ya shabab, cayb namut bi-dun dabka wa aghani!”

Honor and respect were bestowed upon the Syrian male passengers of the Titanic by members of their community—both in their new homes and in the towns and villages they had left behind. For Syrians, the widely shared story of first-class passenger Ida Straus refusing to leave her husband, Isidor, echoed the same devotion seen in steerage passengers Butrus and Zahiya. Likewise, the heroic acts of John Jacob Astor, William Stead, and Archibald Butt—who helped women and children into lifeboats—found a parallel in the selfless actions of Niqula Nasrallah and other Syrian men who stepped back so that others might live.

Beirut’s Lisan al-Hal, on May 10th, asserted that there was no difference between the heroism of the prominent men aboard the Titanic and that of the Syrian male passengers (2). They, too, embodied noble values and upright character in their steadfast and courageous efforts to ensure the safety of women and children.

The story of the Titanic is part of the immigration story of both America and Syria. As the years pass and time takes its toll on living memories, recording the events of the disaster and the effects of it serves as a timeless record of the experiences of both victims and survivors, their families and the story of their immigration. It also serves as witness to the heroics of the prominent and famous male passengers of the time and that of the courageous and valiant acts of the Syrian male passengers whose names and actions may otherwise be lost in vicissitudes of history.

From Leila Salloum’s book, The Dream and then the Nightmare: The Syrians Who Boarded the Titanic – the story of the Arabic-speaking passengers (Atlas for Publishing and Distribution, 2011)

Want more articles like this? Sign up for our e-newsletter!

Check out our blog here!