The Mystery of Fátima de Madrid

By Liam Nagle / Arab America Contributing Writer

We have all heard about the various astronomers, philosophers, and masters of the sciences in the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. One such figure from this period was Maslama al-Majriti, also known in Latin as Methilem, a scholar from Madrid during the time of Muslim rule. While he himself is the subject of some debate—due to works published long after his death that are either attributed to him or suspected to be the work of someone capitalizing on his name—there is another mystery surrounding him. This mystery involves his supposed daughter, Fátima de Madrid, who may not have existed at all. Allegedly an astronomer in her own right, if her story is true, she would be one of the earliest known female astronomers, standing out in a career dominated by men.

Her Life, Supposedly

Fátima de Madrid was an Arab Muslim astronomer and mathematician who supposedly lived during the 10th and 11th centuries in Al-Andalus, or Muslim-ruled Spain. Her father, Maslama al-Majriti, was, among other things, an astronomer who lived from 950 to 1007 CE. Little is known about Fátima’s personal life; most of what we know comes from accounts of her career and achievements. She is said to have lived in Córdoba when it was the capital of the Caliphate of Córdoba, which ruled much of the Iberian Peninsula. She was also reportedly fluent in multiple languages, including Arabic, Spanish, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin.

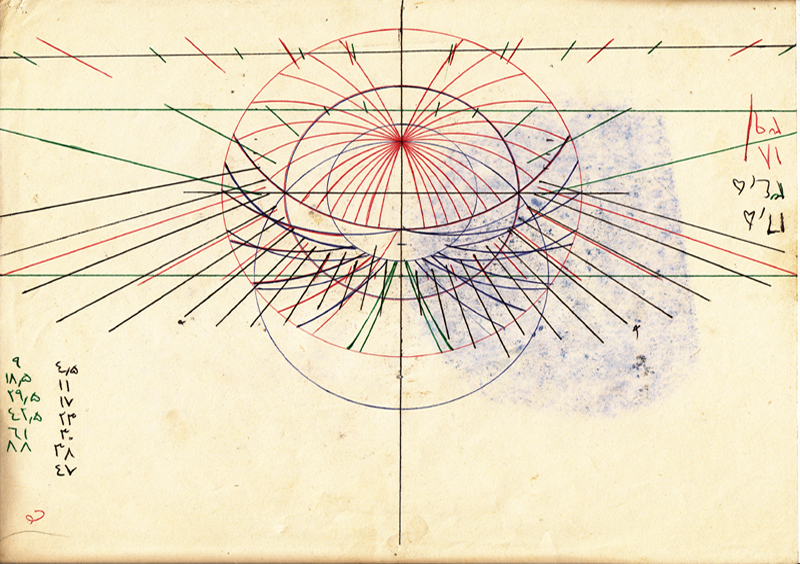

During her career as an astronomer, Fátima de Madrid accomplished a variety of significant feats. She collaborated with her father on several of his works, including editing al-Khwarizmi’s astronomical tables. Together, they adapted the tables by replacing the Persian solar calendar with the Islamic lunar calendar, making them applicable outside of Persia. She also co-authored A Treatise on the Astrolabe with her father and assisted in correcting Ptolemy’s Almagest, the former of which is reportedly held in the monastery of El Escorial.

Fátima’s most influential work, however, was a project she undertook independently. Titled Corrections from Fátima, this was a compilation of astronomical treatises, though no copies of it have been found to date. She also authored several other treatises covering topics such as calendars, ephemerides, and eclipses. Fátima’s career was remarkable—she not only collaborated with her father on important projects but also established her own legacy as a scholar and astronomer.

Controversy over her Existence

Historians are skeptical about Fátima de Madrid’s existence primarily because she went unmentioned for several centuries. While the male-dominated society of her time might have dismissed or overlooked her achievements, the complete lack of any historical reference raises significant doubts. The first known mention of her is in 1924, in a Spanish encyclopedia called the Enciclopedia universal ilustrada europeo-americana, commonly referred to as the Enciclopedia Espasa. This extensive work, spanning over 100,000 pages, delves deeply into numerous people, places, and subjects, but its late mention of Fátima has led to questions about her authenticity.

Although Fátima de Madrid’s name appears in the 1924 encyclopedia, historians remain skeptical of the accounts. Historian Ángel Requena Fraile notes that such an ambitious encyclopedia is bound to contain errors, potentially introduced by “unscrupulous or careless copyists,” leading to the creation of myths. He cites another questionable figure, Luciniano, the Bishop of Calahorra, who appears in the encyclopedia but is absent from all other historical records. Similarly, historian Manuela Marín argues that Fátima de Madrid is likely a fabrication, widely accepted as truth despite a lack of supporting evidence. To these historians, her inclusion in the encyclopedia, without corroboration from other sources, strongly suggests she never existed.

Conclusion

Fátima de Madrid’s career allegedly ranged from collaborating with her father to publishing her own works—though these works have either never been found or are rumored to be hidden in a monastery in Spain. Did her existence stem from a writer’s inaccurate 1924 encyclopedia entry, or did she actually exist? For now, contemporary historians largely agree that she did not, but perhaps time will reveal a definitive answer.

Check out our Blog here!