The Hammams of Damascus - A World of Cleanliness and Relaxation

By: Habeeb Salloum/Arab America Contributing Writer

It is said that to visit a hammam (traditional bathhouse) in Damascus will not only make you cleanse your body but will also give you an elated feeling of comfort and relaxation. For many of the uninitiated, once tried is rarely forgotten. The medieval hammams, especially in Damascus, are institutions which have stood the test of ages.

In this oldest continuously inhabitant city on earth, their history goes back to Canaanite times, if not before. They have remained the mainstay of society through the Greek, Roman, Byzantine and Islamic times. Even in our modern age, they are still very much alive.

In the early eras, especially during Greek and Roman centuries, the hammams were places of pleasure and revelry. However, at the dawn of Islam, the hammams, adapted from the Roman and Greek predecessors, became locales in which to instill in the people a love of cleanliness and, at the same time, a place to socialize. Despite early warnings in the Islamic world that hammams were places for the dangerous indulgence of the pleasures of the flesh, they subsequently become an important social center in much of the Islamic world.

Unlike the Romans, who bathed in pools of water, Muslims preferred the cleaner method of splashing themselves from basins. A hammam was frequently located near a khan where weary travellers would have a chance to cleanse themselves, or near a mosque as part of the commercial complex provided by a wealthy patron to generate income for the mosque’s upkeep.

Every city in the Islamic world had its hammams. In some large urban centres like Damascus and Baghdad, they were to be found in the hundreds. Even in small villages throughout the far-flung Muslim lands there was to be found at least one hamman. People rarely ever had baths in their own homes. Hammams were, especially for women, a place for cleanliness and their social centre.

For women whose freedom was very restricted, hammams became a passion. The bathhouses were their only contact with the outside world – a type of medieval woman’s private club. They were the places where many affairs, gossip and rumors would start. In affluent households, visiting women friends would be taken to the hammam where they would be washed, massaged, and dressed in the most luxurious outfits provided by their hostess. For all women, a trip to the hammam was in itself a real treat.

Today in the larger towns, even though rarer than in the past, hammams continue to exist. Even though, unlike in the past, most homes have up-to-date bath facilities, to go to a hammam is still considered by many residents of large cities like Damascus as a chance, not only to cleanse oneself, but also as a time to relax, have a massage, sip coffee, converse with friends and, at times, have a meal with family and friends – a light meal of mujaddara (lentil pottage) is favoured for these occasions. The hammam remains a social club par excellence where often customers will spend up to six hours socializing.

The ritual of taking a bath in the hammam is a set procedure as old as time. During my first visit to Damascus, with a friend, I decided to go through this ritual to experience the art of common bathing, practiced since the beginning of Middle Eastern civilizations. I was excited but at the same time apprehensive.

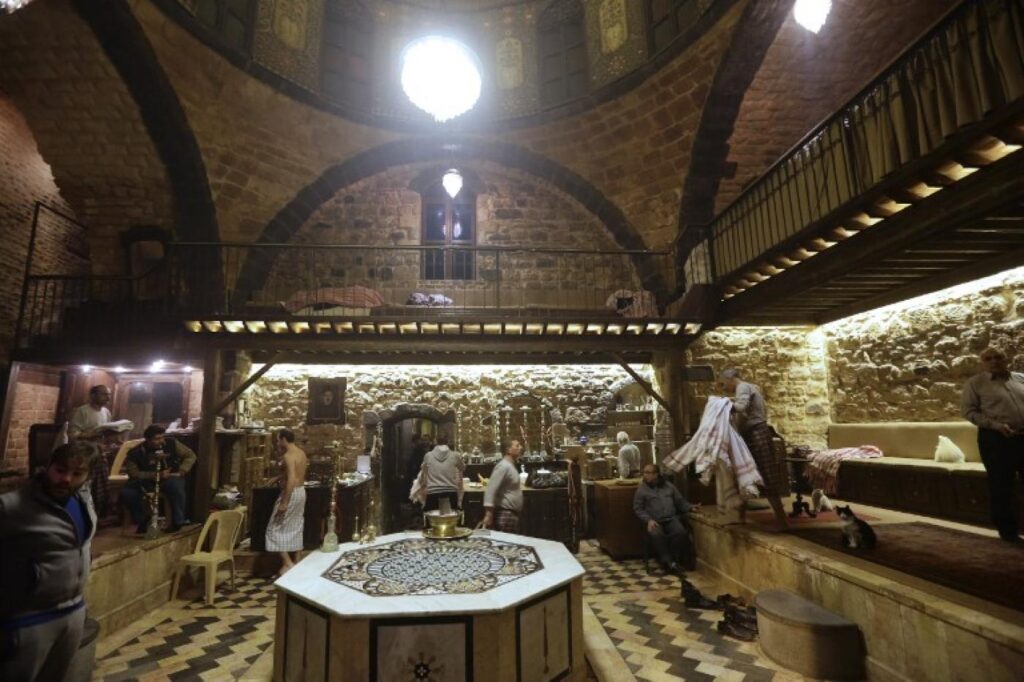

Making our way through the narrow streets of old Damascus, we came to an ornamented small stone doorway – hammams have a small entrance with the purpose of keeping in the heat which is supplied by ducts running under the floors. We first entered the Maslakh (disrobing/change room) where our clothing and valuables were safely stored.

We were then given a cloth wrap and qabqabs (wooden clogs) and an attendant led us to bayt al-hara (heat or sweat room), heated by burning crushed olive pits or garbage. The boiling water is then carried by pipes in the wall with steam vents. The smaller hammams have only one sweat room, but the larger ones, like the one we had entered, have a series of sweat rooms where each room becomes progressively hotter as one moves along.

Next, we moved into the warm room and I felt a great relief from the searing heat in the sweat room. Here, I had paid a small fee for a huge muscular attendant with large hands to give me a scrubbing. Using a coarse camel-hair mitten, he almost rubbed my skin off as he scrubbed the hidden dirt under my skin. I thought that I was skinless, but after he washed my body clean, I felt a sense of enjoyable relaxation. This was crowned by a massage for which I had paid a little extra. Expertly, he seemed to destroy every nasty little knot lurking in the muscles between my neck and shoulders. XI felt now that I had been reborn.

After we returned to the disrobing area, this feeling of satisfaction stayed with me as I sat down on a bench and relaxed, swathed in towels enjoying a hot cup of tea. I suddenly realized that I could not remember when I had felt so good. Every muscle in my body seemed to be content and my skin had a deep feeling of cleanliness. A pleasant warmth crept over me and I could have easily fallen asleep.

I felt contentment as I conversed with several similarly swathed fellow bathers. They were amazed that one who lived in North America was bathing with them in an Arab hammam. I soon became the star of their conversation, but I was hardly listening, as I thought about rushing back to my hotel room and crawling into bed.

From the hundreds that dotted Damascus in the Middle Ages today there are only 12 bathhouses still working while the rest have been transformed into restaurants and coffee shops. No doubt all these places of cleanliness will soon disappear except those left as tourist attractions.