The Arab Revolt and the European Colonization of the Arab World

By Liam Nagle / Arab America Contributing Writer

The Arabs in the Middle East and North Africa were largely under the dominion of the Ottoman Empire up until 1914. However, when the Ottomans went to war with powers in Europe, the Arabs rose in revolt. But while the war was won, and Ottoman domination was reduced, the Arabs were now ruled by new masters.

The Arab Revolt

In June of 1914, Europe erupted into a war of enormous proportions. With the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, a complicated system of alliances drew nearly every country on the continent into the conflict. However, it wouldn’t be called a “World War” if it just took place in Europe. When the Ottoman Empire joined the war in October of 1914, they found themselves pitted against the United Kingdom and France, resulting in the war’s expansion to the Middle East and Northern Africa.

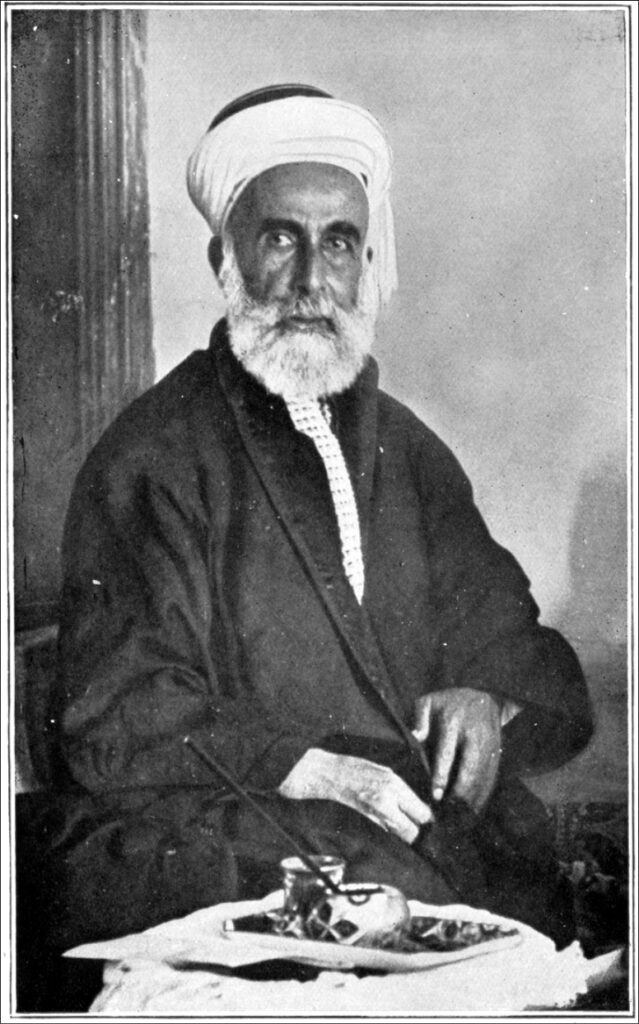

The Ottoman Empire was already very weak during this period, having already suffered from political turmoil, military defeats in previous wars, and ethnic/nationalist uprisings. Given this, the UK and France sought to exploit these vulnerabilities in the “sick man of Europe”. The UK, in particular, began talks with Hussein bin Ali, the Sharif of Mecca within the Ottoman Empire. Called the McMahon-Hussein correspondence, the British and Hussein bin Ali agreed that, in exchange for Hussein’s rebellion against the Ottomans, the British would lend military assistance, as well as allow for the creation of a new, independent Arab state in the Middle East.

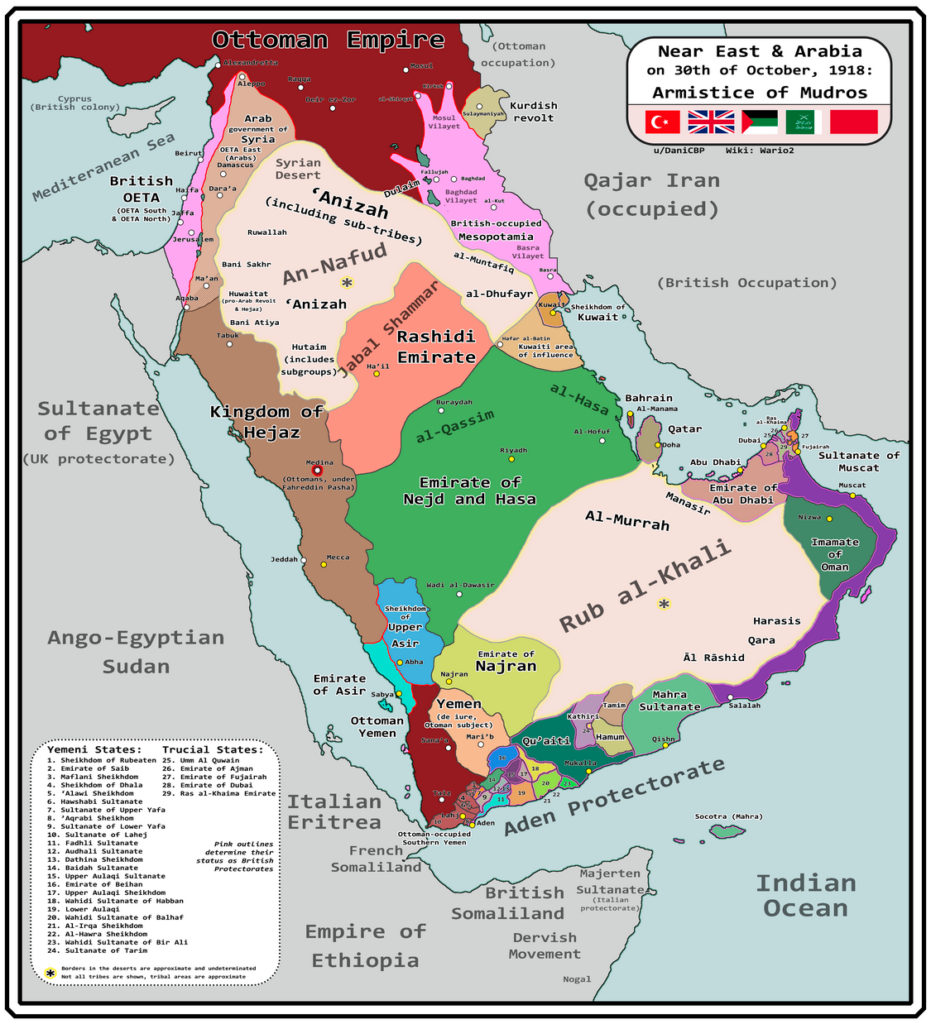

The rebellion, now known as the “Arab Revolt” or the “Great Arab Revolt”, officially started on June 10th, 1916. Hussein bin Ali proclaimed himself king of the new Arab state, known as the Kingdom of Hejaz. Encompassing around 30,000 troops, including British and French military forces, the revolt succeeded in taking much of the western Arabian peninsula from the Ottomans, who were spread thin across several other fronts. The Arabs and British expanded further north over the next two years; first moving for the Transjordan region in 1917, they reached as far as Damascus, which they captured in October of 1918.

Despite this, the Arab Revolt’s relationship with the British and French was not absolute. In November of 1917, the UK’s Balfour Declaration announced its support for a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, many of the details of which (including what a “national home” meant, or how much of Palestine the “national home” would take up) were left vague. Just one month after this in December 1917, the Bolsheviks in Russia leaked the Sykes-Picot Agreement made between the UK and France, which revealed both countries’ intentions to divide the Middle East into spheres of influence at the end of the war.

The leaders of the Arab Revolt were outraged by both of these propositions, believing them to violate the McMahon-Hussein correspondence, and causing a great rift between the two sides. Britain attempted to rectify the situation, stating that the Balfour Declaration’s “national home” did not threaten the “political and economic freedom” of the Arab Palestinians. Concerning the Sykes-Picot agreement, the British outright lied to King Hussein. Britain sent two letters stating that the Sykes-Picot Agreement was a fabrication – made by the Ottomans to sew distrust between the Arabs and the British. Upon receiving these letters, King Hussein believed the British. Despite both of these British blunders, the Arab Revolt continued to cooperate with the British Empire.

The End of the War

At the end of the war in November of 1918, the Arab Revolt had stretched from Mecca to Aleppo. The Ottoman Empire had lost almost all of its lands outside of Anatolia, with much of the control going to Britain, France, and the Arab Revolt. Britain, seeking to establish friendly, pro-British Arab states, embraced the “Sharifian Solution”. Through this, four different states would be created by installing King Hussein and his sons to power: Hejaz, in Syria (including Transjordan), Upper Mesopotamia, and Lower Mesopotamia. However, future events would complicate these plans resulting in the creation of four states elsewhere: Syria, Iraq, Transjordan, and Hejaz.

In Syria, the Arab Kingdom of Syria would be ruled by King Faisal, the third son of Hussein. However, this kingdom would not last long. The British, despite helping the creation of the Arab Kingdom of Syria, withdrew their support in 1919 at the Paris Peace Conference, opting to support the French claim over Syria. France initially attempted to uphold the existence of the Syrian kingdom in exchange for being the sole supplier of advisors to its government, but the anti-French and independence-minded government in Syria rejected these conditions. Given this, France opted to invade Syria instead. King Faisal, wishing to avoid bloodshed, surrendered to French forces. The Arab Kingdom of Syria would be disbanded, in favor of the new French Mandate for Syria and Lebanon, in July of 1920.

In Iraq, Britain instead unified both Upper and Lower Mesopotamia into a single mandate officially called the Kingdom of Iraq in 1920. Abdullah bin Hussein, the second son, was offered the position of king but he declined. Instead, the position went to Faisal after he had fled from the French in Syria. The Kingdom of Iraq, although technically ruled by the Arabs under King Faisal I, would de facto remain under British control until independence in 1932.

In Transjordan, after the French invasion of Syria, the area fell into a sort of “no man’s land”, where Britain refused to control the territory to avoid “any definite connection between it and Palestine”. Instead, Abdullah bin Hussein entered the territory in 1921 where, after a conference with the British, it was agreed that he would administer the territories under the auspices of the British Mandate for Palestine. King Abdullah I would continue to rule Jordan up to its independence from Britain in 1946.

King Hussein ruled the Kingdom of Hejaz after the war. However, his relationship with the British would remain strained. King Hussein refused to ratify the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, as well as a 1921 British proposal that supported French dominion over Syria. Further negotiations between Hejaz and Britain were attempted over the next three years, but ultimately proved fruitless. Eventually, Britain would withdraw their support for the Kingdom of Hejaz, instead opting to support of Ibn Saud, who controlled another nearby state. In 1924-1925, Ibn Saud would conquer the Kingdom of Hejaz and depose King Hussein, eventually resulting in the creation of Saudi Arabia.

In spite of British promises to grant the creation of a single Arab nation-state, conflicting goals between the French, Zionists, and Britain’s own imperial ambitions complicated their agreements. As such, only two of these four states, ruled by the descendants of Hussein bin Ali, would remain past the 1930s: Iraq and Jordan – and they would remain under heavy British influence for years to come.

Check out our Blog here!