The 1952 Egyptian Revolution: A Turning Point in Modern Arab History

By: Rania Basria / Arab America Contributing Writer

The 1952 Egyptian Revolution, often known as the “23 July Revolution,” was a watershed point in Egyptian and Arab history. This revolution not only ended decades of British rule, but it also established the modern Egyptian state, changing the region’s socio-political environment. Arab America contributing writer, Rania Basria, delves into the revolution, led by the Free Officers Movement, a group of nationalist military officers, that ended British dominance in Egypt and marked the beginning of profound political, social, and economic reforms.

The 1952 revolt stemmed from widespread unhappiness with the governing monarchy and its ties to British colonial interests. King Farouk I, who seized the throne in 1936, was regarded as a symbol of corruption and ineptitude. His lavish lifestyle and failure to meet the demands of the Egyptian people fueled widespread resentment. Social and economic inequities, along with high unemployment rates and poor living circumstances, fostered Egyptian unrest.

Furthermore, the 1948 Arab-Israeli War harmed the Egyptian government and military. The Arab troops, notably Egypt’s, were defeated by the newly founded State of Israel, resulting in national humiliation. The conflict highlighted the Egyptian military and government’s flaws and corruption, escalating the clamor for reform among both the Egyptian people and military personnel.

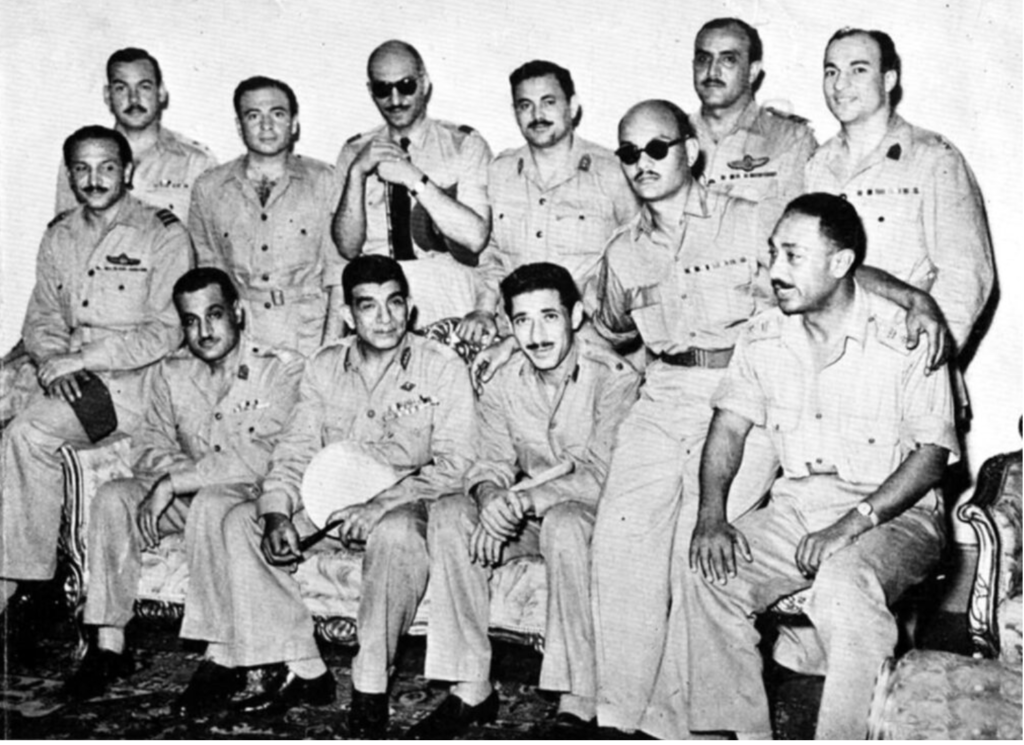

The foundation of the Free Officers Movement, a covert group inside the Egyptian military created in 1949, served as the spark for the revolution. Gamal Abdel Nasser, a youthful and charismatic commander, spearheaded the campaign alongside other officers who shared his views, notably Anwar Sadat. Their major objective was to topple the monarchy and establish a government that would meet the Egyptian people’s demands and ambitions.

The Free Officers were driven by a combination of nationalism, anti-colonial indignation, and a desire for societal fairness. They were influenced by the worldwide movement of decolonization and anti-imperialism that swept over Asia and Africa in the mid-20th century. The movement’s philosophy was also influenced by socialist concepts, which sought to decrease social injustice and encourage economic development through land reforms and the nationalization of important enterprises.

On the night of July 22-23, 1952, the Free Officers carried out their plot to take control. They staged a coup, seizing control of important government buildings, military sites, and communication hubs in Cairo. The coup was quick and mostly bloodless, with the royal army offering minimal resistance. On the morning of July 23, General Muhammad Naguib, the revolution’s figurehead commander, declared the coup’s success and the end of the monarchy.

King Farouk was compelled to abdicate and go into exile in Italy. The Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) was formed to administer Egypt, with Naguib as president and Nasser as vice-president. However, it quickly became apparent that Nasser was the true driving force behind the revolution.

The new government swiftly proceeded to solidify control and carry out its reform plan. One of their first measures was to abolish all political parties and outlaw the Muslim Brotherhood, a well-known Islamist group. The Free Officers also implemented a series of land reforms to redistribute agricultural land from the rich elite to the poor peasants. These measures were intended to alleviate long-standing imbalances in the rural economy and gain popular support for the new administration.

The revolutionary government also took substantial steps, such as nationalizing vital sectors and expanding the public sector. This was part of a larger attempt to eliminate foreign influence and guarantee that Egypt’s riches were used to benefit its people. Education and healthcare were also addressed, with measures underway to boost literacy rates and enhance access to medical services.

While General Naguib first served as president, Gamal Abdel Nasser emerged as the new government’s dominating figure. Nasser, a charismatic and ambitious leader, progressively marginalized Naguib and took full power in 1954. Under Nasser’s leadership, Egypt’s internal and foreign policies became increasingly radical and forceful.

Nasser’s vision for Egypt was based on Arab nationalism and socialism. He aimed to make Egypt a dominant force in the Arab world while also advocating for anti-imperialism and pan-Arab unity. Nasser’s domestic policies included further nationalization of industries, land redistribution, and the development of social welfare programs.

Nasser’s foreign policy was defined by a dedication to non-alignment and anti-colonialism. He was a key figure in the formation of the Non-Aligned Movement, which attempted to place countries outside the influence of the primary Cold War powers, the United States and Soviet Union. Nasser also took a strong stance against Western imperialism, particularly during the 1956 Suez Crisis.

The Suez Crisis began with Nasser’s desire to nationalize the Suez Canal, which had previously been managed by British and French interests. This move was interpreted as a strong assertion of Egyptian sovereignty, prompting a military response from Britain, France, and Israel. However, international pressure, mainly from the United States and the Soviet Union, compelled the invaders to leave, cementing Nasser’s reputation as an anti-imperialist and increasing his support in the Arab world.

The 1952 Egyptian Revolution had a deep and long-lasting influence on Egypt and the greater Middle East. It marked the end of centuries of monarchy and foreign rule, creating the framework for the modern Egyptian state. The revolution also sparked kindred nationalist movements throughout the Arab world, helping to fuel the wave of decolonization that swept over Africa and Asia in the mid-20th century.

Under Nasser’s leadership, Egypt pursued a path of modernization, social reform, and regional leadership, but not without substantial difficulties and failures. The revolution’s legacy is multifaceted, with both triumphs and problems. While it was successful in toppling a corrupt and ineffective monarchy, the years that followed were marked by authoritarianism, economic hardships, and social unrest.

Nonetheless, the 1952 Revolution remains a watershed point in Egyptian history, representing the Egyptian people’s aspirations for independence, social fairness, and national pride. Its influence may still be felt today, as Egypt navigates a difficult and ever-changing regional and global context.

Check out our Blog here!