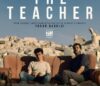

Small farmers struggle worldwide, but Palestinian farmers really have it rough

Fawzi Ibrahim, a Palestinian farmer, waited two months for the Israeli army to give him access to his wheat fields this year. He had only two days to try to plow and plant 50 acres of wheat, under the guard of Israeli army soldiers. The Israeli settlement of Esh Kodesh is behind him on the hill, and settlers watch from the road. (Anne-Marie O’Connor/For The Washington Post)By Anne-Marie O’Connor

The Washington Post

Palestinian farmer Fawzi Ibrahim is proud of his heirloom corn, whose kernels ripen in iridescent shades of red, blue and gold like jewels.

But what makes it priceless are the obstacles he faces to grow his crops.

Small farmers struggle worldwide. But international experts say Palestinian farmers face disabling odds in the 60 percent of the West Bank that is under full Israeli control and is home to some 400,000 Jewish settlers.

As settler agricultural start-ups get prioritized access to water, export markets and development rights, the Israeli occupation is roiling the centuries-old pastoral life of Palestinian farmers, experts say, adding fuel to a conflict in which land is a trigger.

For years, Israeli settlers have chased Ibrahim’s tractor, threatened him, yelled at his Israeli soldier escorts, tried to burn his fields and warned that letting him farm would risk bloodshed, according to the Israeli group Rabbis for Human Rights.

Ibrahim must coordinate with the Israeli army because his land is in a security zone abutting Israeli outposts, the group said. But he and his lawyer waited eight weeks for permission to plant 50 acres of winter wheat in just two days, under the guard of two jeeploads of Israeli soldiers. A human rights worker and Israeli settlers looked on.

Ibrahim said he fears he will suffer thousands of dollars in farming losses again this year.

“They’re making us poor,” he said.

A recent U.N. report said the Israeli occupation has set off a “continuous process of de-agriculturization” in the Israeli-controlled West Bank, depriving the Palestinian economy of potential agriculture revenue of $700 million, by World Bank estimates, as Israeli settlers bar Palestinians from crops, grazing lands and springs.

The World Food Program is providing food assistance to 75,000 Palestinians in Area C, according to local spokesman Raphael du Boispean.

A December report by the Israeli human rights group B’Tselem said Israeli settlements have overtaken a half-million acres of former Palestinian lands in Israel-controlled Area C, which was placed under full Israeli control in 1990s accords. B’Tselem said 200,000 to 300,000 Palestinians live in Area C.

“What the Israeli settlers are doing in those areas is a disaster,” said Avshalom Vilan, executive director of Israel’s powerful Farmers Federation, a mainstream private farmers group. “They’re stealing from the lives of their Palestinian neighbors, and making their lives impossible.

“It’s in Israel’s interest for Palestinian farmers to work their land peacefully,” Vilan said. “We will all pay for this.”

Yishai Fleisher, the international spokesman of the Jewish settlement in Hebron, said that “life will be much easier for Palestinian farmers under a one-state solution, in which minorities are incorporated into the state of Israel.”

“Jews live in the settlements because they are the heartlands of the Bible and Jewish history,” Fleisher said. “Many of us are also in the settlements to thwart the two-state solution, because we think it’s wrong, unjust and dangerous.”

Spokesmen for the Israeli settlers’ Yesha Council, the Agriculture Ministry and the office of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declined to comment.

Israel’s Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories Unit, or COGAT, said 5 percent of Palestinian fields “adjacent to Israeli villages” in the West Bank require Israeli permission and escorts “to ensure that their work goes undisturbed . . . while implementing their right to cultivate their land.”

COGAT said it provided 600 such escorts in 2016 for the Palestinian olive harvest, a target of Israeli settler attacks.

The Rand Corp. said settler attacks quadrupled from 2006 to 2014 and are “an important trigger of Palestinian retribution.”

A 2013 World Bank report said the agriculture contribution to the Palestinian economy declined by more than half in Area C in the past two decades, with Palestinians losing access to water and land, and less than 1 percent of land designated for Palestinian construction.

Meanwhile, Israeli settlement agriculture rose 35 percent, by World Bank estimates, with growing exports to Europe and Russia.

COGAT said Israelis provide training to Palestinian farmers and operators of a German-financed wastewater treatment plant, and oversaw the shipping of 113,000 tons of Palestinian produce outside the West Bank in 2016 — a tiny fraction, said Palestinian Authority official Marwan Durzi, of the export potential of 2.6 million tons of Palestinian agriculture.

Durzi said settler appropriation of springs forces Palestinian villagers to drastically reduce village herds, while Israeli authorities deny Palestinians permits for wells and cisterns and demolish nonpermitted irrigation.

Since most Palestinian families in Area C live partly on farming, “it’s crippling,” Durzi said.

Ibrahim was a scion of a prosperous family in the 1980s, when Israelis took 2,000 acres of family farmland and olive groves in the West Bank, ending his agronomy studies at Texas A&M University.

Israeli rights groups helped him recover 100 acres.

Ibrahim watches subsidized Israeli agriculture start-ups flourish on land he claims at Shvut Rachel, a Jewish outpost founded in the name of Rachela Druck, a settler killed in a 1991 Palestinian attack on a bus. Shvut Rachel’s most famous onetime resident, Jack Teitel, was convicted in 2013 for killing two Palestinians.

Alleged Hamas militants shot Israeli student Malachy Rosenfeld on the highway as he traveled through the area in 2015 — just a few miles from Ibrahim’s land.

In January, Israeli authorities indicted four Israeli settlers who lived on a hilltop near Ibrahim’s fields in Geulat Zion — once home to an Israeli accused of the 2015 firebomb killing of a Palestinian mother, father and baby in nearby Duma — after Israeli undercover police allegedly caught them going after Palestinian farmers with stones and truncheons.

Settlers “do what their government wants them to do,” Ibrahim said. “They want them to take the land.”

Ibrahim said his family once farmed alfalfa and barley on land seized for vineyards by the Esh Kodesh outpost, which has Israeli-supplied water.

But Aaron Katsof, an Esh Kodesh vintner, insisted that “there was nothing here.”

An Israeli court ordered a settler to clear his vineyards off a parcel of Ibrahim’s land by December 2015, and though the settler finally moved this year, he was convicted of kidnapping and beating a Palestinian shepherd, and Ibrahim says he is still afraid to reclaim the land.

Ibrahim remembers the days when younger Palestinians waited for the harvest to marry, and patriarchs lived well from the land.

To Ibrahim’s generation, he said, “land is life.”

Diabetes has forced him to rely on a cane, but Ibrahim said he is determined to end his days as a farmer.

“If I leave, they’ll take the land,” he said. “Then I’ll have nothing.”