SOURCE: THE ECONOMIST

BY: A.V.

THE END of January marks the start of the Cairo International Book Fair, the largest gathering of its kind in the Arab world. Writers and readers from all over the region meet to swap tomes and discuss this year’s theme: “soft power, how?” A good question, especially for Egyptians. After all, the country’s distinctive dialect once ruled across the region. Its decline speaks to the restless state of the modern Middle East, and the decline in Egypt’s influence over it today.

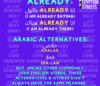

Arabic is sometimes considered a language family, rather than a single language. Education and writing is in “modern standard” Arabic, but each region has its own distinct spoken variety, and those dialects separated by enough distance are not mutually comprehensible. They differ at every level from grammar to vocabulary to pronunciation. (Egyptian is perhaps most easily distinguished by its use of a g-sound where most other dialects have a j.) Like all of the Arabic vernaculars, Egypt’s is richly infused with local history. Sit down at a Cairo café and the waiter might greet you as basha, borrowed from Turkish pasha and the Ottoman conquest. Ask for a fattura (invoice), or buy a pair of guanti (gloves), and you are using Italian, left behind by a large community that lived in Egypt for over a century. Greek words like tarabeza (table, from trapeza) are common for similar reasons.

From the 1940s, people all over the Arab world grew used to Egyptian. Generously funded by the state, the Egyptian cinema industry was the third biggest on earth in the 1950s. Stars like Faten Hamama and Hend Rostom made crowds from Tripoli to Damascus laugh and cry. Egyptian music was just as popular. Umm Kulthum (picture below) was so famous her monthly radio concerts prompted shopkeepers to close their stores and tune in. It helped that many songs touched on themes like anti-colonialism that struck a chord across the Arab world.

This is no accident: pan-Arab nationalism helped push Egyptian dialect. Flush from victory in the 1956 Suez crisis, and keen to promote Egyptian leadership, Gamal Abdel Nasser (pictured, top), then president, sent hundreds of teachers to Algeria, hoping the locals would dump French and its imperialist overtones (they would have taught standard Arabic, but spoken Egyptian). Nasser himself became known throughout the Middle East for his magnetic speeches on Voice of the Arabs, a Cairo radio station. Though he led the pan-Arab movement, supposedly dedicated to bashing down the differences between Arabs, Nasser used Egyptian dialect to explain highfalutin ideas more simply. When he died in 1970, Egyptian speech was easily the most widely understood across the Arab world, from the Atlantic to the Persian Gulf.

Egyptians are still proud of their dialect, and it enjoys more exposure than its cousins elsewhere in the Arab world. While news bulletins are typically in formal Arabic, raucous commentators bicker about politics in Egyptian. This can partly be explained by education. With dismal schools, and illiteracy stuck at 24% , many Cairenes struggle to use formal Arabic. Some linguists even suggest teaching children dialect in school to improve flagging standards.

This is not the whole story, though. After all, even educated Egyptian politicians happily sprinkle debates with more dialect than their counterparts in the Gulf or Morocco. Writers do too. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Ahmed Fouad Negm, a poet, was famous for using dialect in his pithy putdowns of Egyptian politicians. Contemporary writers are following in their path. Tamim Al-Barghouti, another poet, is famous for his biting Egyptian verse. Enas Haleem, a novelist, recently used Egyptian dialect in “Under The Bed”, a short story collection. For its part, this year’s Cairo International Book Fair is honouring Magdy Abdel Rahim, who died last year, and his wide contribution to colloquial Egyptian poetry.

The internet offers yet more chances for Egyptians to explore their vernacular. Ghada Abdel Aal, a pharmacist and writer, started blogging about her love life in colloquial Arabic. She went on to turn her stories into a book, and then a television sitcom. YouTube is another powerful tool. One of the funniest channels is Egyptoon, a show featuring Sawsan and Hamada, her long-suffering boyfriend. “You are everything in my life!” Hamada cries, using the classic Egyptian phrase kula haga (everything). Egyptian Arabic even has its own Wikipedia. This is unique for an Arabic dialect, and controversial for those who think that playing up the dialects is a way of intentionally or unintentionally dividing the Arabs.

But if the internet offers a new home for Egyptian, it does the same for other dialects. Their parents may have been stuck with Voice of the Arabs, but young Palestinians and Jordanians can blog or podcast in their own words. A broader collapse in pan-Arabism, alongside that of Egyptian power, hardly helps. “The Arab world is very fractured now,” notes Jonathan Featherstone, a specialist in Egyptian Arabic at the University of Edinburgh. “You don’t have the same unity that you had before.”

This is reflected in Arab culture. Syrian soaps like “Bab Al-Hara” (“The Neighbourhood Gate”) are hugely successful. Blockbuster Turkish shows are being dubbed into Syrian Arabic, too. Arab music has gone the same way. A recent Arab top-ten list featured just one Egyptian song, by Mahmoud El Esseily and Mahmoud Ellithy. The top spot went to Noor Alzien, who sang using the guttural q of his native Iraq. Satellite television helps shoot different dialects to fame, as well. Mohammed Assaf went from a Gaza refugee camp to mega-stardom by winning Arab Idol, a talent show. He sang in his Palestinian colloquial Arabic, proudly telling his audience to “raise the kufiyah!”

Though Egyptian cultural exports have not disappeared—it is still easily the largest Arab country by population—they have certainly slumped. In 2013, the Dubai International Film Festival made a list of the top 100 Arabic films. Thirty-five Egyptian films from the pre-1970s “golden age” made the cut, but only three modern Egyptian movies managed. Some cinemagoers grumble that today’s Egyptian cinema emphasises glamour and women over plot.

Egyptians who could get more exposure overseas are not helped by their government. Ramy Essam, a singer, became famous throughout the Arab world for his revolutionary anthems (notably “Bread, Freedom, Social Justice”). But after getting tortured by police, he fled to Sweden. Bassem Youssef, a comedian, suffered a similar fate. Despite gaining massive audiences with his satirical rants in Egyptian slang, he ended up in Los Angeles following pressure from the Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi regime. Amr Jamal, a translator from Cairo, despairs at these struggles: “Now we are swimming in mud,” he says. A pity—and a mark of how far Egypt has slipped from the rich optimism of Umm Kulthum and Voice of the Arabs.