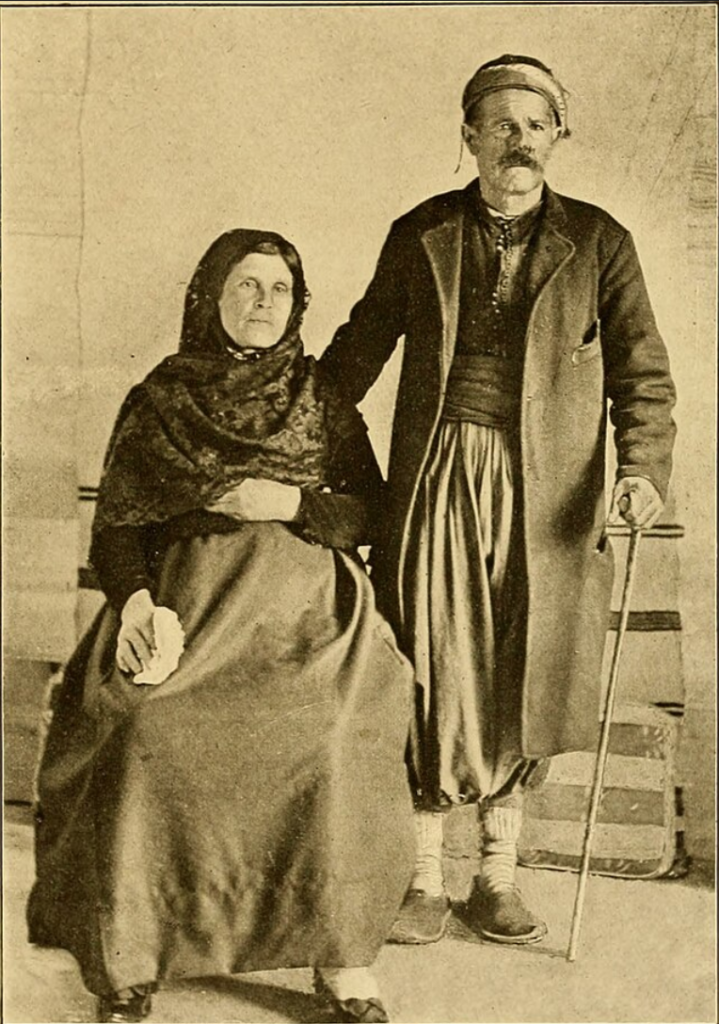

Portrait of 19th-Century Villages in Greater Syria in Rihbany’s Autobiography

By: Arwa Almasaari / Arab America Contributing Writer

In a world where visual records of daily life in 19th Century Greater Syria (or Bilad al-Sham) are scarce, autobiographical accounts become indispensable for understanding the period. Abraham Mitrie Rihbany’s A Far Journey stands out as a pioneering work in this context, being the first Arab American autobiography. Born in Ottoman Syria (now Lebanon) in 1869 and emigrating to the United States in 1891, Rihbany’s narrative offers a rare and intimate glimpse into village life through his personal experiences.

Written initially as a serialized story for The Atlantic Monthly in 1912 and later published as a book in 1914, Rihbany’s work provides a vivid portrayal of his hometown of El Shweir and the more diverse Betater. His observations not only document daily activities and community interactions but also reflect the complexities of the religious and cultural dynamics of his time. As we delve into his story, we gain invaluable insights into the social and cultural fabric of a bygone era, enriched by Rihbany’s unique perspective as both a local resident and an immigrant.

As a minister, Rihbany is keenly interested in observing the interactions between different religious groups and the dynamics within each community’s sects. His book includes detailed passages about daily life in his birthplace, El Shweir (Dhour El Choueir/Dhour Shweir) and Betater (Btater). Through his anecdotal account, readers gain a glimpse into village life from the perspective of a local resident.

Life in El Shweir

Rihbany’s narrative begins in the Christian town of El Shweir, where he notes that all residents are Christians, predominantly Greek Orthodox, with a minority of Maronites and Greek Catholics.

He vividly captures the social life of his hometown, highlighting pastimes such as:

- “Lifting the Mortar”: A strength contest where participants lift a large stone mortar with a wooden handle to shoulder height or higher with one arm.

- “Two-Steps-and-a-Jump”: An exciting game where players would run, jump, and mark their landing spot, striving to outdistance each other.

- Other activities included tossing the ball, debkah dance, card games, riddles, and storytelling about ghosts, saints, and heroes (43-4, 46-7).

Moving to Betater

When Rihbany’s family moves from the Christian village of El Shweir to the more religiously diverse town of Betater, they encounter the Druze community for the first time.

As a devout Christian, Rihbany proudly notes that his father was known as the “Master” (builder), and he himself was referred to as “Abraham, the Master’s son,” akin to how Joshua was known as “the son of Nun.” Additionally, their family was called “Shweiriah” after their hometown, in keeping with the ancient Syrian custom of identifying people by their place of origin, similar to “David, son of Jesse, the Bethlehemite” (76).

Welcoming of Minorities

Rihbany warmly remembers their early years in Betater, where the Christian and Druze residents, regardless of social status, generously supported his family. They made the newcomers feel welcome by bringing an abundance of produce during the fruit and vegetable season. In their first two years, they received enough golden grapes to produce a year’s supply of raisins, wine, and vinegar. (78). This generosity and welcoming spirit in Betater left a lasting impression on Rihbany. By highlighting the harmonious coexistence and support among diverse religious communities, Rihbany underscores the importance of welcoming immigrants like himself to the US.

Part of the Community

One particularly memorable event for Rihbany was the awe-inspiring manifestation of sympathy from the people of Betater when his five-year-old brother died. Because the family had no relatives in the town “to comfort [them],” and even though the deceased was only a child, his funeral equaled in dignity that of an influential citizen.

The “comforters” who came seemed to Rihbany like a multitude that no man could number. Although, according to custom, only a few of the young Sheikhs represented the noble clan at such a funeral, nearly the entire clan attended in this case. They came up to the family’s house with their attendants of the Druze commoners, assuring Rihbany’s sorrowing father that his affliction was theirs also. They insisted that he should not consider himself “ghareeb” or a stranger in their midst because they thought of him as one of them and that their homes and all they possessed were at his disposal. (78-9).

This poignant experience exemplifies the profound sense of community and compassion that transcended religious and social boundaries in Betater, offering Rihbany’s family solace and a deep sense of belonging amidst their grief.

Rumors of the “Other”

Despite Rihbany’s family being warmly welcomed as a religious minority, receiving generous gifts, and being comforted during difficult times, the fear of the “Other” persists in the big city. On their way to Beirut, his father gave young Rihbany detailed instructions on how to behave. He was advised not to stare at “Mohammedans” (i.e., Muslims), identifiable by their white turbans, as they viewed Christians as “kuffar (infidels) and enemies,” ready to harm them at any provocation.

In their presence, Rihbany was to adopt a reverential and humble demeanor. He was also cautioned to stay close to his guardians, as there were fears that Jews might kidnap and kill him, with tales suggesting that “the sons of Abraham feasted on the blood of Christian children.” (80-81). Western myths about Jews had reached the Middle East. One reader asked al-Bayan editors about the Wandering Jew, but the editors dismissed it as a foolish ancient myth.[i]

This stark contrast between lived experience and persistent rumors underscores the ongoing fears in the broader societal context despite the personal kindness and acceptance encountered in smaller communities. Both in the mahjar and the East, authors recognized Jews as integral to their society, with Jewish communities in cities like Beirut, Damascus, Jerusalem, and Cairo being protected by Ottoman and Islamic law (Matar 21). Indeed, many mahjar authors, particularly those in the early Arab American diaspora, viewed being Syrian as encompassing a society with diverse religious identities (Womack 42).

Significance of Rihbany’s Narrative

In summary, A Far Journey by Abraham Mitrie Rihbany offers a rare and detailed look into life in 1800s Greater Syria through the eyes of a local resident. Rihbany’s first-hand account captures the rich social fabric of his hometown, El Shweir, and his experiences in the more diverse Betater. His observations on daily life, community interactions, and the warmth of his new neighbors provide invaluable insights into the era. Yet, despite the hospitality and generosity he received, Rihbany’s narrative also highlights the enduring presence of fear and prejudice towards the “Other” in broader societal contexts. This dual perspective enriches our understanding of historical and cultural dynamics, making Rihbany’s autobiography a significant contribution to the historical record.

[i] Al-Bayan 1 (1897–8), 55–7.

References:

Rihbany, Abraham Mitrie. A Far Journey. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914.

Matar, Nabil. United States Through Arab Eyes: An Anthology of Writings (1876-1914). Edinburgh University Press, 2018.

Womack, Deanna Ferree. “Syrian Christians and Arab-Islamic Identity: Expressions of Belonging in the Ottoman Empire and America.” Studies in World Christianity, vol. 25, no. 1, pp. 29–49.

Arwa Almasaari is a scholar, writer, and editor with a Ph.D. in English, specializing in Arab American studies. She often writes about inspirational figures, children’s literature, and celebrating diversity. You can contact her at arwa_phd@outlook.com

Check out our blog here!