Pathbreakers of Arab America--Kamal Boullata

By: John Mason / Arab America Contributing Writer

This is the thirty-fifth of Arab America’s series on American pathbreakers of Arab descent. The series includes personalities from entertainment, business, sports, science, academia, journalism, and politics, among other areas. Our thirty-fifth pathbreaker is Kamal Boulatta, a Jerusalem-born Palestinian American visual artist and art historian. Boulatta, born in 1942 and passed away on August 6, 2019, has left a magnificent collection of mostly abstract art for all to see. Kamal’s art reflects deep feelings about Palestinian identity as an occupied people in their homeland and, for himself, as someone separated from his homeland – in exile.

An amazing artist even at a young age, Kamal Boulatta became a renowned Palestinian abstract painter

As a small boy in Jerusalem, Boullata recalls, according to Wikipedia, “sitting for hours on end … in front of the Dome of the Rock, engrossed in sketching its innumerable and unfathomable geometric patterns and calligraphic engravings.” As an adult, Kamal still valued those patterns, which reveal themselves plainly in his later work. He remembered, during an interview, “I keep reminding myself that Jerusalem is not behind me; it is constantly ahead of me.” Though Kamal’s family belonged to the Greek Orthodox Church, his religious sentiments seemed to range from trans-Islamic to universalist and later included references to Sufism.

Clear from the beginning that he was already a budding artist, Boulatta enrolled at the Fine Arts Academy in Rome, followed by a stint at the Corcoran School of the Arts and Design, Washington, D.C. Given his interest in Middle Eastern art history, he was awarded a Fulbright Senior Scholarship in 1993-94 to conduct research on Islamic art in Morocco.

Kamal’s prolific work has been exhibited throughout Europe, the United States, and the Middle East and is permanently displayed in several prominent museums. He and his wife, Lily Farhoud, lived and worked in Menton, southern France, and later in Berlin, Germany, where he was a resident fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study. Berlin is where he died.

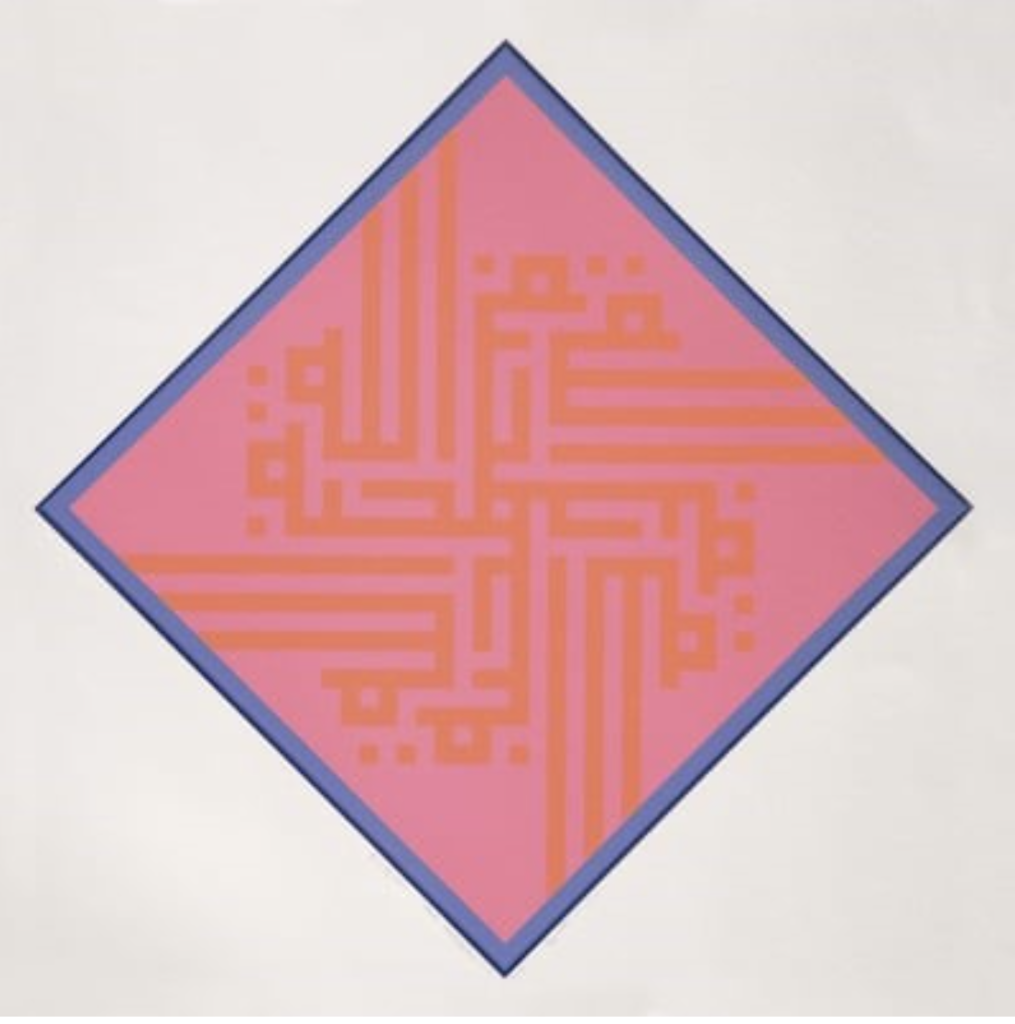

Boullata’s work was mainly done in acrylic paint on silkscreen, though he is also known for some watercolors. He used the angular Arabic script, known as Kufic, as the foundation for his paintings. His compositions are thus based on geometric designs, serving as a representative form of art. The theme of Kamal’s paintings revolves around Palestinian identity, embracing Palestinians living under occupation and exile.

His art is part of the Hurufiyya Art Movement, named after the Arabic term ‘harf’ or alphabetic letter. Here, it refers to Kamal’s use of calligraphy as a graphic element in his artwork, more typically in his abstract work. In addition to his art, Boulatta is the author of perhaps the “most important book on the subject of Modern and contemporary art from Palestine, titled: ‘Palestinian Art: from 1850 to the Present.’”

Painter and historian Boulatta “channeled the anguish of living in exile through his works”

Fellow Palestinian from Jerusalem, Steve Sabella, shared several important thoughts on his good friend, Kamal, following Kamal’s death. His commentary appeared in the magazine, ‘Palestine Art Middle East.’ Sabella referred to Boulatta as “the most forward-thinking person I knew,” noting that his friend often repeated the phrase, “look forward.” This phrase was a metaphor for “the pain of him losing Palestine, his homeland,” whose anguish he channeled into his art and writing. Sabella claimed that everything Kamal produced “was about light and transcendence.” Both artists agreed that, ultimately, “Jerusalem is the capital of [their] imagination[s].”

In a ‘Middle East Report’ tribute to Boulatta, its editors spoke of how, on Kamal’s death, “It took a miracle, and intensive efforts by his family and Jerusalem lawyers to convince the Israeli Ministry of Interior to allow the family to repatriate his body from Berlin to his birthplace. Around a thousand relatives, friends, diplomats, and Jerusalemites from all walks of life, including his neighbors from the Old City, squeezed into the small Orthodox Church at the foothill of the cemetery.” Kamal was buried in the Orthodox Cemetery at Mt Zion on August 19.

The priest officiating Boulatta’s funeral, the Archbishop of Sebastia, Father Hanna Atallah, spoke in fiery language about the deceased. “Kamal has come back, over the bayonets and barbed wires set up by the occupiers to block the sons and daughters of this country from being reunited with their homeland…. His dead body has arrived, but his soul will live forever in his beloved Jerusalem.”

At the church’s door, a printed placard was placed by a Palestinian news agency over a candle and a bowl of incense: “Kamal Boullata was born in Jerusalem in 1942 and grew up in the Old City. According to the records of the Orthodox Church of Jerusalem, his family traces its history in the Old City for over 600 years. For half a century, since 1967, he was barred from Jerusalem because he happened to be out of the country for an exhibit in Beirut in 1967 when the Israeli occupation started. All his efforts to return to Jerusalem failed, except for a brief visit in 1984, memorialized in the film ‘Stranger at Home.’ However, Jerusalem always stayed in his heart and in his art.”

Kamal was only a young man when he was refused the right to return to Jerusalem by the Israeli government following the 1967 Arab-Israel war. He had been in Beirut at the time, exhibiting his work, according to “Middle East Eye” (MEE), and he spent the next 50 years living between the United States, Morocco, and France before moving to Berlin in 2012. Seven years later, when Boullata was working towards the exhibition, ‘Jerusalem in Exile,’ in 2019, he died. He was collaborating with his wife, Lily Farhoud, on that exhibit.

Though a Christian by birth, Kamal “worked very much through the tradition of the icon, and more of his work is overtly Islamic in terms of its use of geometry and the spiritual inspiration behind it.” His insistence on Jerusalem as a shared space among Jews, Muslims, and Christians shows up readily in his art in its themes and titles. According to MEE, Boulatta rejected the idea that his art could “be pigeonholed as a single identity … [it is] very, very important for Arab art, for Islamic art, we are seeing increasingly that we are talking about universal accessibility, not narrow identities, and he resisted that all his life.”

Finally, Kamal is defined as “not simply a Palestinian artist. He is Palestinian, and he is a Jerusalemite. That’s how he would describe himself. His work was always universal.”

Sources:

–“Kamal Boulatta,” Wikipedia Biographies of Arab Americans, 2024

–“Remembering Palestinian artist Kamal Boullata: ‘the most forward-thinking person I knew’,” Palestine Art Middle East, 8/22/2021

–“Kamal Boulatta, Meem Gallery, Munich, (no date)

–“A Tribute to the Palestinian Artist Kamal Boullata,” Middle East Report Online, November 11, 2019.

–“Medieval to modernist: Palestinian artist inspired by Jerusalem’s melting pot,” Middle East Eye, by Tim Cornwell, 2/14/2020

John Mason, Ph.D, focuses on Arab culture, society, and history, is the author of LEFT-HANDED IN AN ISLAMIC WORLD: An Anthropologist’s Journey into the Middle East, New Academia Publishing, 2017. He has taught at the University of Libya, Benghazi, Rennselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, and the American University in Cairo; John served with the United Nations in Tripoli, Libya, and consulted extensively on socioeconomic and political development for USAID and the World Bank in 65 countries.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of Arab America.

Check out our Blog here!