Opinion// By Degrading Arabic, Israel has Degraded Arabs

A banner supporting the creation of a single state for Israelis and Palestinians which reads in Arabic: “If I had to choose between one state and two states, I would choose the one state”AP Photo/Nasser NasserIronically, amid the discussion of Israel’s ‘Jewish and democratic values,’ a section of the law that might have called for preserving Arabic’s official status would have been the only part of it to be both Jewish and democratic

SOURCE: HAARETZ

BY: YONATAN MANDEL

The nation-state law is stirring fierce debate among both Jews and Arabs in Israel, about whether such legislation was needed, and about its various clauses. But a majority of MKs cast an unhesitating vote in favor.

As someone who studies the status of the Arabic language, I feel compelled to address the section of the law that removes Arabic’s standing as an official language. Beyond the practical implications of this, there is another aspect: It signals that Israel seeks to be a foreign implant among its neighbors and to eliminate the connection between Arabic and the Jews.

Here are nine points to consider, now that Arabic has been erased as an official language:

1. Lowering the status of Arabic, and of Arabs: This is what the law is trying to put over on us. It states that Arabic will no longer be an official language but in the same line says that its status “will not be harmed.” The semantics won’t fool anyone: If Arabic was an official yesterday but isn’t one today, then its status – and that of Arabic-speakers – has been harmed. Essentially, Israel is saying to its Arab citizens: From now on, we do not officially recognize your language and your culture.

2. Protest and language: The link between language and identity is a Gordian knot that is at the forefront of the latest research on the subject. For instance, the first “war” of the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine is called “the war of the languages” and had to do with opposition to the decision of the Ezra company to teach at the Technion and the Reali School in German. The big anti-apartheid protests in South Africa also marked a major milestone in wake of a decision related to language: In June 1976, the Soweto riots erupted after the authorities announced that Afrikaans and English would be the languages of instruction in the schools. It’s hard to understand why the Israeli government felt it was so urgent just now to press on this sensitive spot.

3. Arabic and the 29th of November: Israel is always pointing out that the basis for the state’s establishment was the Zionist movement’s acceptance of the 1947 UN Partition Plan. Regardless of the nature of the plan, it must be recalled that the basis for Israel’s establishment, its consent to the Partition Plan, rests on a promise at the heart of that plan: a pledge by the Jewish state not to harm the rights of minorities, with an explicit mention of “preserving linguistic rights.” Erasing the status of a language that was an official language of the country for many decades would be a blatant violation of the commitment upon which Israel’s establishment was based.

4. Jewish-Arab relations and the government’s recommendations: Demoting Arabic’s status is not just opposed by human rights organizations; it also goes against the recommendations of a governmental commission of inquiry. It’s astounding to go back to the report of the Or Commission, which investigated the events of October 2000 in regard to Jewish-Arab relations in Israel. The commission, headed by Judge Theodor Or, found that “the government must act to erase the stain of discrimination against its Arab citizens.” It’s not surprising that the government-appointed commission also discussed linguistic rights, noting that the recognition of Arabic as an official language was one of the few collective rights that Arab citizens enjoyed and that should be preserved. Precisely the opposite of the aim of the nation-state law.

5. Arabic and the Arab world: Israel is located in a region where Arabic is the lingua franca. Israel does not have warm peaceful relations with any Middle Eastern countries despite having its hand “outstretched in peace.” Will eliminating Arabic’s status help Israel convey a message of peace to its neighbors? Had Arabic never been an official language here it would be one thing, but by the act of officially erasing the language of the Middle East, Israel is sending an unfortunate message to all its neighbors: The official status of Arabic may have been a slight show of respect for the local language, but now that is being taken away too.

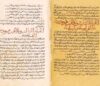

6. Arabic and Jews, Arabic and Hebrew: Arabic is not only the language of Muslims, Christians and Druze in the Middle East. Arabic was the most common language of a majority of Jews until the 12th century, and continued to be a language of creativity and communication and philosophy for most of the Jews who lived in the countries of the East. Some of the most important Jewish religious and philosophical writing, from Musa ibn Maimun to Said ibn Yusef al-Fayumi (Maimonides and Saadia Gaon), was written in Arabic and Judeo-Arabic. Moreover, of all the world’s widely spoken languages today, Arabic is the closest to Hebrew. They are “Semitic sisters,” as Jewish scholars referred to them, “and every root that exists in Hebrew also exists in Arabic,” as Eliezer Ben-Yehuda noted. Thus, the erasure of Arabic also means the erasure of part of the Jewish past, and of the Jewish connection to the Arabic language, the Middle East and the local peoples.

7. Knowledge of Arabic among Jewish Israelis: The most recent survey about Jewish Israelis’ knowledge of Arabic had disturbing findings. Conducted by a Tel Aviv University polling institute in 2015, the survey found that less than 10 percent of Jewish Israelis said they “understand Arabic”; only 6.8 percent of Jewish Israelis said they “understand Arabic letters”; 2.4 percent said “they could read a short text in Arabic”; 1.4 percent said they could compose a brief email in Arabic and just 0.4 percent said they could “read a novel in Arabic.” The situation has never been worse. The generation that knew Arabic as a mother tongue is disappearing. For the first time in the last 1,500 years there is no Jewish composition in Arabic in this country. And erasing Arabic’s official status is the farthest thing from a solution to this problem.

8. Opposition of the professional organizations: Scholarly professional organizations opposed the elimination of Arabic’s official status in Israel. The Israeli Association for the Study of Language and Society, the lone professional association concerned with the connection between languages and populations in Israel, issued an opinion saying that its members “adamantly oppose the language section of the bill, as any erasure of language could have dire consequences.” The same goes for the Academy of the Arabic Language in Israel, founded as the result of a government law, which said “In light of the steep retreat in Arabic’s standing, considered action should be taken to improve its status.” And most scholars of Arabic studies feel the removal of Arabic’s official status is bad and foolish. Only the MKs thought differently.

9. Arabic as an official language – whom does it hurt?: “Official language” is a general status given to a language and every country chooses how to interpret that. One may require knowledge of the official languages for a government job; others may choose to make the official language visible on its currency. South Africa has 11 official languages. Does this mean that every lecture at every public university is given in 11 languages? Of course not. But it is a way for the state to say to its citizens: You are part of us. In Israel, since 1948, there have been two official languages, just as there are two peoples who live in the country. Preserving Arabic’s official status is also important on the level of principle, and eliminating that status will have much harsher repercussions than maintaining the status quo ante would have had.

The Knesset has had its say and the nation-state law has been enacted. Ironically, amid the discussion of Israel’s “Jewish and democratic values,” a section of the law that might have called for preserving Arabic’s official status and promoting knowledge of the language would have been the only part of it, in the deepest sense, to be both Jewish and democratic.