Music is Magic in Uniting Arab Americans – How Arab Music Pulls at the Heartstrings, Stirring Nostalgia for the ‘Homeland’

By: John Mason / Arab America Contributing Writer

This past weekend’s celebration by the Arab America Foundation of Arab music, art, and film reinforced the already strong Arab identity with over 1200 in attendance. Here we look at the magical place Arab music plays in the lives of Arabs generally and Arab Americans in particular. Arab music is difficult to untangle because it is played in quarter-tones – notes between notes and due to its uncommon rhythms. To capture the spirit of Arab music, we review the National Arab Orchestra’s finale, Abdel Halim’s song, ‘Sawwah’(سواح) or Wanderer.

Music at Center Stage as Arab America Festival in Washington D.C. brings together Members from 25 U.S. States and numerous Arab Origins

This past Friday-Sunday, the Arab America Foundation brought together at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Arabs from all over the U.S. to give them an exotic, fulsome dose of their own culture. Namely, through music, art and film, the event reinforced the already strong Arab identity of hundreds of attendees. Here we look at the magical place Arab music plays in the lives of Arabs generally and Arab Americans in particular.

While American identity is a defining label for Arabs living in the U.S., the cultural tag of their ancestral place is at least of second-most importance. So, while attendees came from far and wide across the U.S., including the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico, their homelands aren’t far behind in who they believe they are. Thus, we can say the attendees have their origins in Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and Tunisia, as well as Middle Eastern countries, Turkey and Iran.

On Friday evening, it was the cherished National Arab Orchestra (NAO), under Michael Ibrahim’s magical wand, that was the focal point of the audience’s rapt attention. The orchestra enveloped attendees in the mesmerizing songs of Nai Barghouti, Lubana Al-Quntar, and Usama Baalbaki. Millennials, middle-agers and seniors alike were all raptly involved, singing along, clapping, and foot-tapping. Although time seemed to fly by, it was three full hours later that attendees finally had to depart from the packed Kennedy Center Eisenhower Theater.

A Brief Look at How Arab Music Differs from Western Music

A Brief Look at How Arab Music Differs from Western Music

Arab music is difficult to untangle in a way that makes sense to Westerners. To Arabs worldwide, the music just makes sense on a personal and cultural level. It is based on the ‘maqam system,’ according to NAO’s Hasan Habib Touma. This is what gives the music its specific tone, whose intervals are different from the western or occidental tonal system. For first-listeners, Arab music may sound discordant—sounds that may seem as if they don’t belong together.

That is because Arab music is played in quarter tones – these are the notes between notes. They comprise the maqam scale of quarter-tones and three quarter-tone intervals. These are simply not found in occidental music. An example is Lebanese trumpet player Ibrahim Maalouf’s adaptation of his instrument so it would play the quarter tones not possible on the normal trumpet. What did he do? He added a fourth valve to the normal three-valve instrument. That allowed him to play all the quarter-tone notes of Arab music, in addition to western-style music.

Another way of putting this is that the western music scale divides into 12 notes. Because of its use of quarter tones, the Arab scale divides the octave into 24 notes. Another significant difference between the two systems is that Arab music rhythms are more varied than western music. The rhythmic cycle in Arab music is called ‘iqa’at.’ The rhythm is based on patterns of beats that repeat every measure. But it can switch back and forth—the two basic sounds comprising the rhythm have been characterized as a ‘dum‘ or “baselike, sustained” contrasted to the ‘tak‘ sound, which is “dry and sharp.” Drums is what Arab music is all about, some might say.

A final aspect of Arab music is captured by the Arabic work ‘tarab.’ This may not translate easily into English. NAO’s Hasan defines it as “a musical mentality” that creates a certain aesthetic based on the tonal scale and the rhythms. More specifically, tarab has been defined as “the ecstatic feeling that the music produces” or “a heightened sense of emotion or excitement.” Friday’s audience could easily identify with those feelings. A westerner might define the feeling as ‘sounds that are far away, a notion of something foreign, something ‘oriental’—from the exotic east.’

Capturing the Spirit of Arab Music—the Orchestra’s Finale, Abdel Halim’s ‘Sawwah’(سواح) or Wanderer

“And the one step that separates me from my lover is ever so vast”—from Abdel Halim Hafiz’ ‘Sawwah’

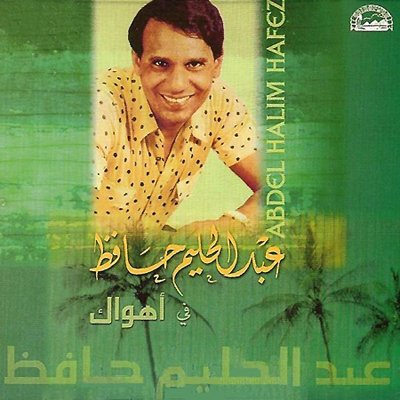

The grand finale of the symphonic event was the NAO and singer Usama Baalbaki’s version of super star Adbel Halim Hafiz’s song, Sawwah—or the wander. Sawwah rates high among many of Abdel Halim’s songs. These include “Ahwak” (I adore you), “Ala Ad El Sho'” (As much as the longing), “Ala Hesb Wedad” (Wherever my heart leads me), and “Betlomooni Leih” (Why do you blame me).

Abdel Halim is one of the most well-known Arab songsters, alongside Umm al-Kulthum and Fairuz. He is known in the Middle East as “the Frank Sinatra of the Middle East.” Let’s try it the other way around—How about, ”Frank Sinatra as the Abdel Halim of the West”? Turnabout is fair play.

Abdel Halim’s rise to prominence did not come quickly. He was initially rejected for his new style of singing. However, according to Wikipedia, he persisted and was able to gain accolades later on. Eventually, he became a singer enjoyed by all generations. He also became Egypt’s first romantic male singer. Abdel Halim played various instruments, including the oboe, drums, piano, oud, and clarinet, among others. He sang in many countries around the Arab World as well as outside, including patriotic songs supporting Egypt’s president Gamal Abdel Nasser.

On a more personal level, at age 11 Abdel Halim contracted schistosomiasis, a rare parasitic water-borne disease—and was afflicted by it for most of his career. Despite this, he remained positive and continued composing and performing his songs. In 1969 Halim built a hospital in Egypt. He purportedly treated the poor, the rich, and the presidents equally. On a personal note, the author was living in Cairo on the date of Abdel Halim’s premature death at age 47 on March 30, 1977. He participated in the outpouring of millions of Egyptians at his funeral. “Overwhelming sadness” does not begin to capture the sorrowful mood of that day.

Singer Baalbaki’s version of Abdel Halim’s “Sawwah’ rocked the house. It was hard to leave the theater as the National Arab Orchestra and Baalbaki brought the proud crowd to their feet. Just for posterity, here’s one person’s translation (translations may differ considerably since the song is basically a love poem) of a portion of ‘Sawwah’ – ‘Wanderer.’

Wandering,

And walking through the lands, wandering.

And the distance between me

And my beloved is vast.

It’s a long journey,

And in it, I’m a stranger.

And the night draws near,

And the sun has returned to its home.

If you find my love,

Greet her for me.

Reassure me about my love,

What has the separation done to the brunette?

Sources:

–“Taking Back our Narrative: Honoring Arab Heritage Culture and Identity through Music, Art and Film,” Arab America Foundation in cooperation with The Kennedy Center and Mellon Foundation, Washington D.C., 2/17-19 2023

–“Overview of Arab Music—Hasan Habib Touma has described Arab music in five components,” National Arab Orchestra (no date)

–Bridging Arabic And Western Music With An Unusual Instrument, NPR, 3/31/2013

–“Sawwah,” Abdel Halim Hafiz, lyrics translate

John Mason, PhD., who focuses on Arab culture, society, and history, is the author of LEFT-HANDED IN AN ISLAMIC WORLD: An Anthropologist’s Journey into the Middle East, New Academia Publishing, 2017. He has taught at the University of Libya, Benghazi, Rennselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, and the American University in Cairo; John served with the United Nations in Tripoli, Libya, and consulted extensively on socioeconomic and political development for USAID and the World Bank in 65 countries.

Check out our Blog here!