Lebanon before Independence

By Liam Nagle / Arab America Contributing Writer

Lebanon is one of the smallest, yet one of the most diverse, states in the Middle East and North Africa region. Encompassing a wide variety of ethnic groups and religions, the country finds itself treading a delicate balance between them, as well as its hostile neighbors. But it wasn’t always this way – the country was only formed as a result of the French colonization of the region. To truly understand how Lebanon came to be, we have to look back to this time period.

Ottoman Rule

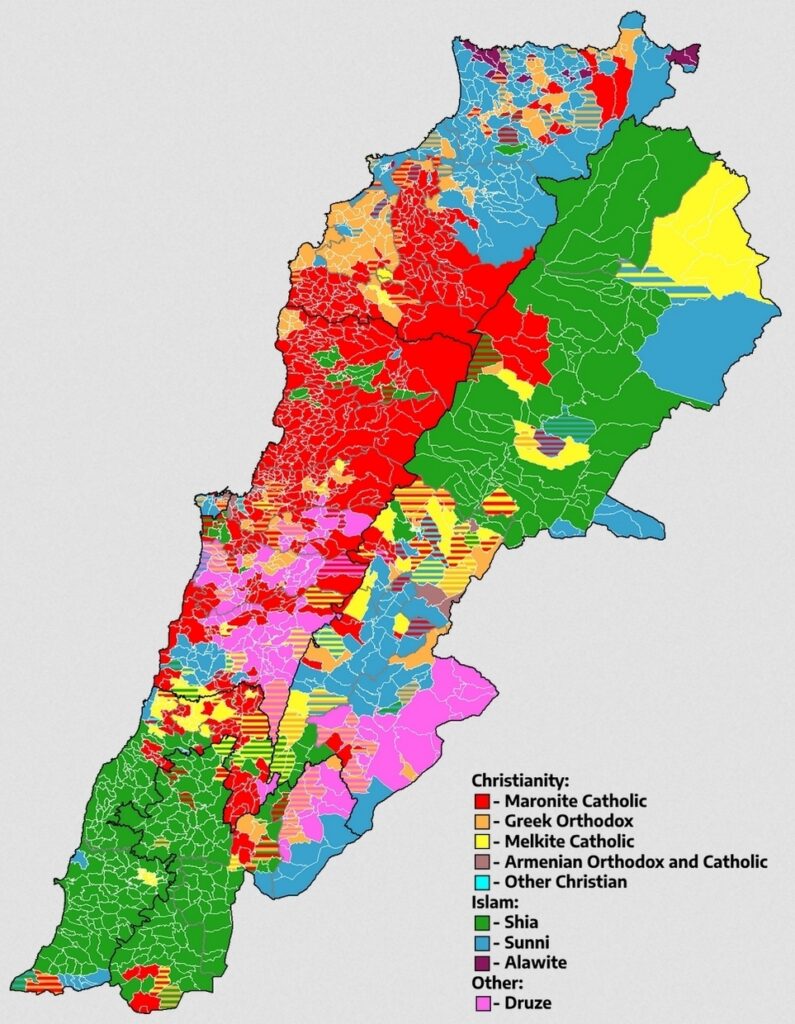

Lebanon consists of three major ethno-religious groups, whose numbers varied across time. In the early 1900s, the largest of these groups were the Maronites. The Maronites are a Syriac Christian group who adhere to the Maronite Church, an autonomous Eastern Catholic church. They are primarily located in the western parts of the country. Another group are the Sunni Arabs, who are located in several large pockets in northern and eastern Lebanon. Finally, the last major group are the Shia Arabs, who live in areas of northeastern and southern Lebanon. There are a variety of smaller ethno-religious groups as well, including Druze, Alawites, as well as both Greek and Armenian Orthodox and Catholics. However, while there are large pockets of each ethnic group, it is worth mentioning that many of these communities live amongst each other. Up into the early 1900s, there weren’t necessarily clear boundaries between many of these groups, and conflict between them was more limited.

Prior to French colonization, the region was controlled by the Ottoman Empire. The region had come under their dominion after defeat of the Mamluks in the early 1500s, and had remained in their control ever since. During the reign of the Ottomans, the authorities were largely only able to control the urban centers, while the rural areas were mostly under the control of local tribal leaders. Nevertheless, religious and ethnic autonomy was granted through the millet and iqta systems. However, problems began to arise in the 1800s. Increasing class and sectarian tensions saw animosity grow between the ethnoreligious groups that would inhabit Lebanon. For example, a partitioning of Maronites and Druze populations by the Ottomans resulted in a civil conflict between them, as well as massacres being perpetrated primarily against the Christians. It was during this time period where France increasingly allied itself with the Maronites of the region, who even militarily intervened in the country following Ottoman approval. Tensions calmed following this, and the Ottomans remained in control of the region.

But entering the 1900s, the Ottoman Empire was viewed as becoming increasingly weak. A variety of reasons are posited as to why the Ottomans were in a decline, varying from economic difficulties, rebellions, rivalries with European powers, and military defeats. Whatever the case, Europeans were now referring to the once-great empire as “the sick man of Europe” and eyeing it for potential colonial prospects. When World War One broke out, the Ottomans opted to side against the French and British. But this proved to be a fatal mistake for the empire – the French and British forces decimated Ottoman forces in the Middle East and North Africa, making it from the Arabian Peninsula to as far as Aleppo in modern-day Syria, before the war came to an end.

French Rule

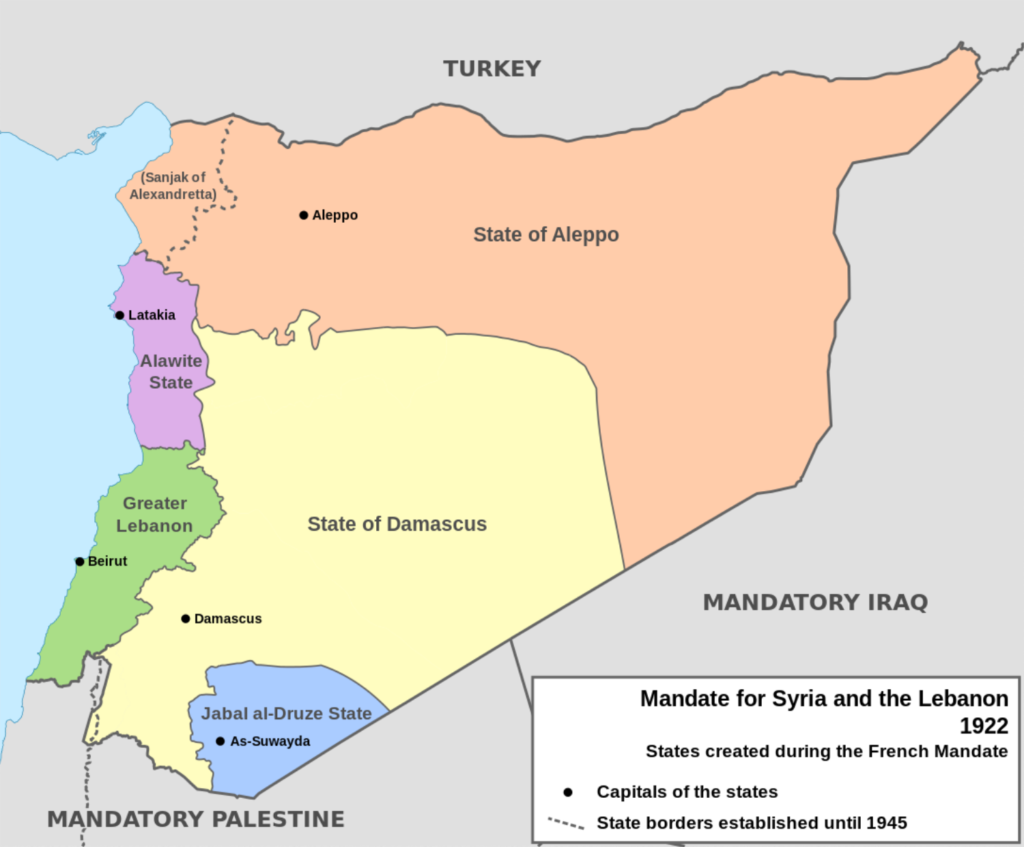

In accordance with the Sykes-Picot Agreement and the Treaty of Sèvres, France took control of Lebanon and merged it with Syria, creating the new Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon. Lebanon was granted a smaller state within this mandate, which would be called Greater Lebanon. The territory of Lebanon was expanded from its previous Ottoman-ruled subdivision, incorporating a wider population of Shia and Sunni Arabs. A census conducted in 1932 showed that the 51.2% of the population was Christian (made up of Maronites, Greek Orthodox/Catholics, etc.), while 48.8% of the population was “Muslim” (made up of Sunni and Shia Arabs, but also including Druze which are definitively not Muslim). As a result, the French adopted a policy of dividing powers between these groups. The president of Greater Lebanon would be Maronite, the prime minister would be Sunni Muslim, and the speaker of the legislation a Shia Muslim. In spite of this, the already strongly pro-French Maronites would generally be favored by French authorities. For example, the Maronite president of Greater Lebanon would select the Sunni prime minister. Another example was in a political deadlock in 1932, which although could have resulted in a Muslim president, ended with France suspending the constitution and expanded the preexisting Greek Orthodox president.

At the outbreak of World War Two, the entire French Mandate was briefly under the control of the Nazi-controlled Vichy French government. But with Britain fearing the security of its own colonies, they invaded the mandate and effectively granted control to the Free French government. In 1940, Free France pledged that Lebanon would become fully independent. However, in November of 1943, elections in Lebanon saw a pro-independence government elected. They unilaterally declared independence from France, and the French ended up reneging on its word by arresting these government officials. A new Lebanese government was quickly formed, but this government also refused to consult the French government – instead stating that the French must consult the imprisoned officials. With this, as well as increasing pressure from both the Lebanese people and abroad, the French opted to release their prisoners and allow them to return to governing office. After having been ruled by the French, as well as the Ottomans before them, Lebanon’s independence was now guaranteed.

Independence

The immediate post-independence period in Lebanon saw the creation of the controversial National Pact. Using the 1932 census as a basis, a new government structure formed that tried to tread the delicate ethnoreligious balance. This National Pact had several principles, but two became extremely important in the years to come. The first one detailed Lebanon’s future relationships with other countries – Lebanon would not pick sides in foreign affairs, choosing not to become western-aligned or Arab-aligned. The second one detailed how the new government would be structured, ensuring different political offices would be controlled by different ethnoreligious groups. Many of the same structures from the French mandate would remain – the president would remain Maronite, the prime minister would be Sunni Arab, and the speaker would be Shia Arab. The legislature would also have a ratio of six Christians to five Muslims. Although this system would be restructured over subsequent decades, the National Pact would remain the defining governing system of Lebanon.

Lebanon’s increasing sectarianism can be rooted in the 1800s and 1900s under Ottoman and French rule. Lebanon emerged as a governing body under the Ottomans, but further expanded under the French mandate, and finally became independent in 1943. Although many of these communities had lived amongst eachother for centuries before, sectarian tensions came to a head in the 1800s and 1900s – the worst iterations of which would come in the years after independence. Nevertheless, the National Pact remains a contentious topic in Lebanon; some see it as maintaining stability and order, while others see it as an outdated and unjust system that needs to be abolished. Maybe we will see where it takes us in the decades to come.

Check out our Blog here!