Karimeh Abbud: The First Palestinian Lady Photographer

By Arwa Almasaari / Arab America Contributing Writer

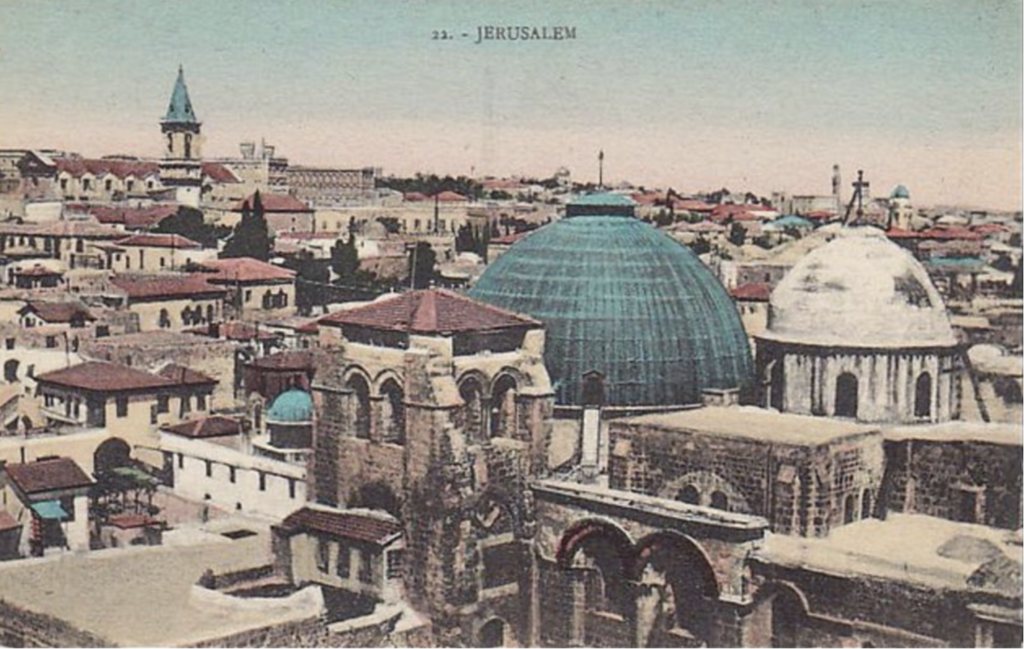

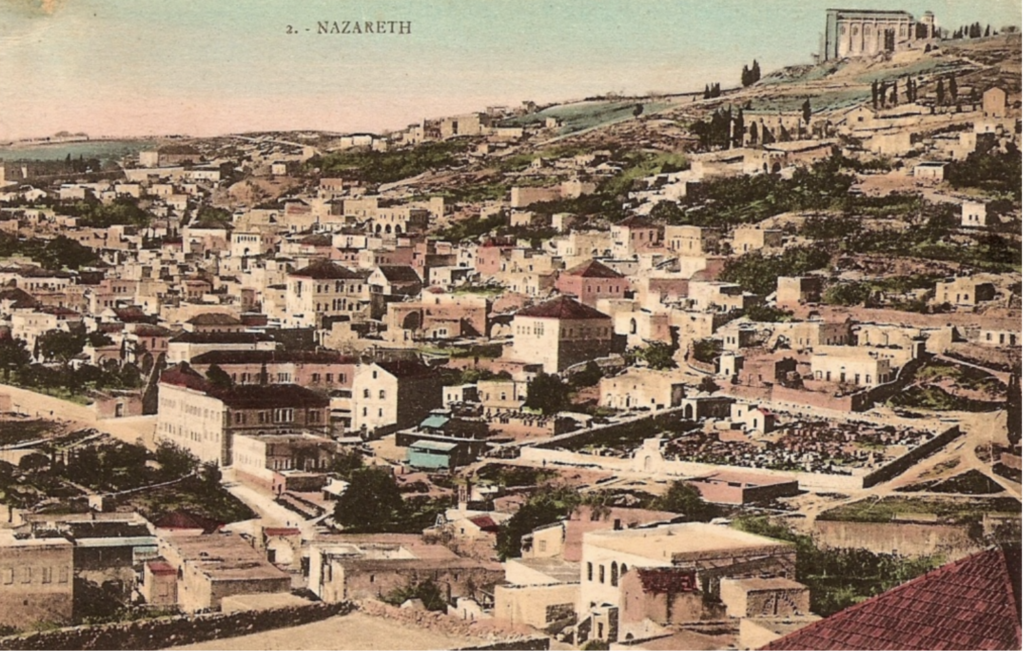

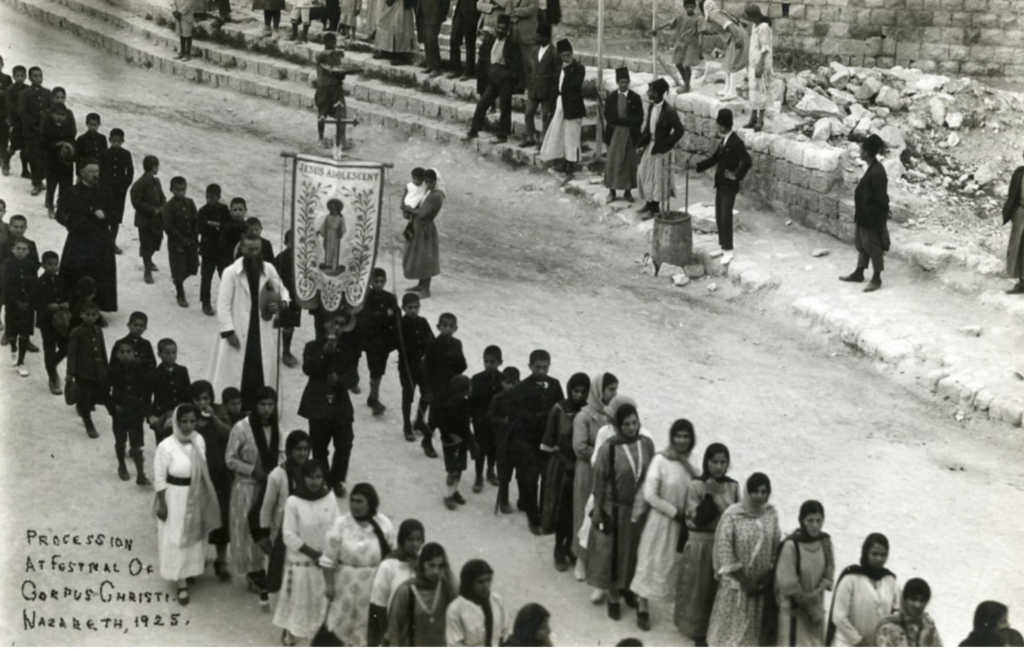

Karimeh Abbud, born in Bethlehem in 1893, made history as Palestine’s first professional female photographer. Her work, encompassing personal portraits and stunning landscapes, offers a rare visual record of daily life and prominent landmarks in early twentieth-century Palestine. Decades later, her recently discovered photographs inadvertently challenge the “land without people” claim, serving as compelling evidence of Palestine’s thriving communities.

Early Life and Education

Source: Mrowat, Ahmed. “Karimeh Abbud Early Woman Photographer”

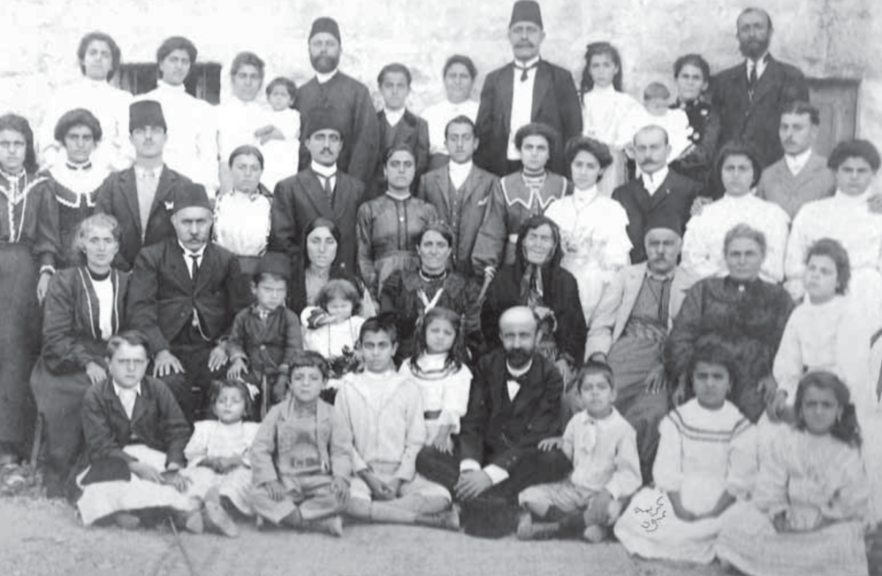

Karimeh Abbud was born in Bethlehem on November 13, 1893, to a Lutheran family. Her ancestors were from Khiyam, South Lebanon, but her family settled in Nazareth in the mid-nineteenth century, where her grandfather worked as a pharmacist. Her mother, Barbara Badr, was a teacher, and her father, Said Abbud, was a pastor. Karimeh and her three brothers and two sisters were nurtured in an environment that valued education and creativity. Later in life, she married Faris Tayeh, and they had a son named Samir, who was born during their brief stay in Brazil.

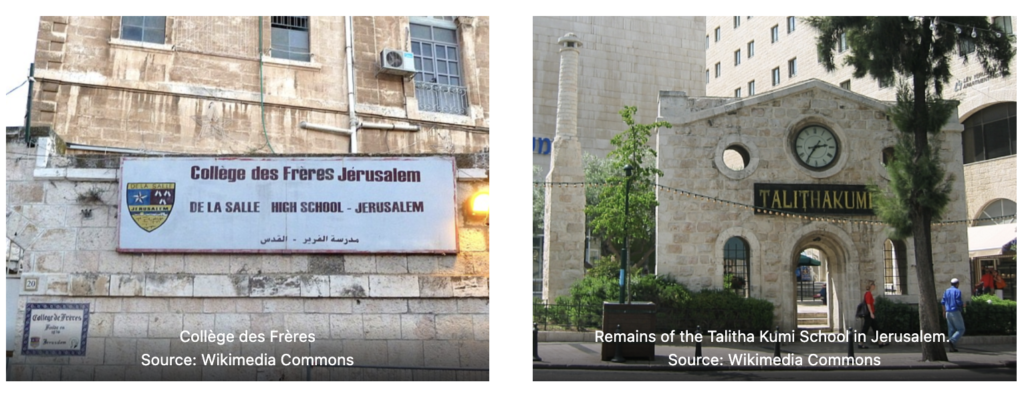

Abbud’s education began in Bethlehem, where she attended primary school. For secondary education, she attended Talitha Kumi School and Collège des Frères in Jerusalem. She then pursued Arabic literature at the American University of Beirut. Her family’s Protestant background fostered close relationships with English missionaries in the area, which contributed to her proficiency in English.

Photography Career

Her photography journey began in 1913 when her father gave her a camera for her seventeenth birthday. With this gift, Abbud started exploring the world through her lens, often accompanying her father on his work trips. She captured the beauty of places like Bethlehem, Tiberias, Nazareth, Haifa, and Caesarea. Some scholars speculate that she learned the art of photography from an Armenian photographer.

After completing her studies in Beirut, Abbud returned to Palestine with a clear vision for her future. She set up a home studio in Bethlehem, where she took portraits of women, children, and weddings. This marked the beginning of her professional career. The earliest signed photograph we have of hers is dated October 1919.

By the early 1930s, Abbud had established herself as a respected photographer known for her stunning color prints. She imported photographic paper from Egypt and developed her prints herself, earning a reputation for quality and artistry. Being a female photographer made her especially popular with women who sought her out for portraits. This increased demand for her services in various cities across Palestine, including Gaza, Jaffa, Haifa, and Jerusalem.

With a car at her disposal, Abbud traveled extensively, documenting landmarks across Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan while also visiting clients who requested her services. Given her husband’s financial struggles, Abbud likely became the primary breadwinner for her family.

As her business flourished, Abbud expanded her operations, opening photography studios in Nazareth, Bethlehem, Haifa, and Jaffa. Her work beautifully depicted the daily lives of Palestinians, capturing a diverse range of subjects from peasants to the middle class.

Sadly, Karimeh Abbud’s life was cut short when she passed away on April 27, 1940, after battling tuberculosis. She was buried in the cemetery of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bethlehem, leaving behind a legacy that would only gain recognition decades later.

It is important to note, however, that scholars are divided on the date of her death. While some sources state 1940, others suggest 1955. I base my information on the birth and baptism records that mark 1940 as the year of her passing.

Legacy and Rediscovery

In 2005, historian Issam Nassar highlighted Abbud’s contributions in his book Laqtat Mughayira [Different Snapshots]. The following year, her work resurfaced when Israeli antique collector Yoki Boaz discovered a collection of her signed photographs in an abandoned house in Jerusalem’s Qatamon neighborhood. Researcher Ahmed Mrowat soon acquired these photographs, expanding his collection with more albums from the Abbud family in Nazareth. Many of these photographs bore Abbud’s stamp, proudly displaying her name in Arabic, “Karimeh Abbud musawwirat shams [sun photographer],” and in English, “Karimeh Abbud lady photographer.

Karimeh Abbud’s legacy received a tribute in 2016 when Google honored her with a Doodle featuring her holding a camera. That same year, Dar al-Kalima University College for Arts and Culture in Bethlehem launched the Karimeh Abbud Photography Competition Prize. This initiative aims to inspire young Palestinian photographers to follow in her footsteps and pursue their passion for photography.

Her Work

Bibliography:

“Karimeh Abbud – Artists (1893 – 1940).” Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question – Palquest, https://www.palquest.org/en/biography/29763/karimeh-abbud. Accessed 23 Aug. 2024.

Karimeh Abbud: The First Palestinian Female Photographer. Directed by Taawon, 2016. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XfyIJmh-jVo.

Mrowat, Ahmad. “Karimeh Abbud: Early Woman Photographer (1896-1955).” Institute for Palestine Studies, https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/77884. Accessed 23 Aug. 2024.

Mrowat, Ahmed. “Karimeh Abbud Early Woman Photographer (1896-1955).” Jerusalem Quarterly, no. 31, 2007, pp. 72–78.

Arwa Almasaari is a scholar, writer, and editor with a Ph.D. in English, specializing in Arab American studies. She often writes about inspirational figures, children’s literature, and celebrating diversity. You can contact her at arwa_phd@outlook.com

Check out our blog here!