Islamic Art in the Metropolitan Museum

By: Souria Dabbousi / Arab America Contributing Writer

The Islamic art in the Met’s collection dates from the seventh through the twenty-first century. With pieces from as far east as Central Asia and Indonesia and as far west as Spain and Morocco, it has more than 15,000 artifacts that represent the immense diversity and breadth of Islamic cultural traditions. In addition to some Turkish textiles in 1879 and some seals and jewelry from Islamic nations in 1874, the Museum also obtained its first sizable collection of Islamic artifacts in 1891 through a gift from Edward C. Moore. Since then, the collection has expanded thanks to donations, bequests, and acquisitions as well as excavations that the Museum supported at Nishapur, Iran, in 1935–1939 and 1947.

The Damascus Room

The Damascus Room is divided into two sections: a raised, square seating space (tazar) and a tiny antechamber (‘ataba), accessed by a doorway from a courtyard. Originally, there used to be a wall with a cabinet where guests may enter the room through.

Rich Damascene homes would occasionally renovate reception areas to reflect changing fashions and interests in home décor. As a result, homes in Damascus’s ancient city, as well as their interiors, seldom belong to a single building period.

The relief design on the woodwork is created with vivid egg tempera paint, tin leaf with colored glazes, and gesso coated in gold leaf. The distinctive Ottoman-Syrian technique and style known as “ajami” produces a rich texture with different surfaces that respond to variations in light.

The ‘ajami decoration’s color scheme was once far more vibrant and diverse than it is now. In order to maintain the surfaces, a varnish coating was applied on occasion. The Damascus Room’s brilliant surfaces have become muted over time as a result of additional varnish layers darkening.

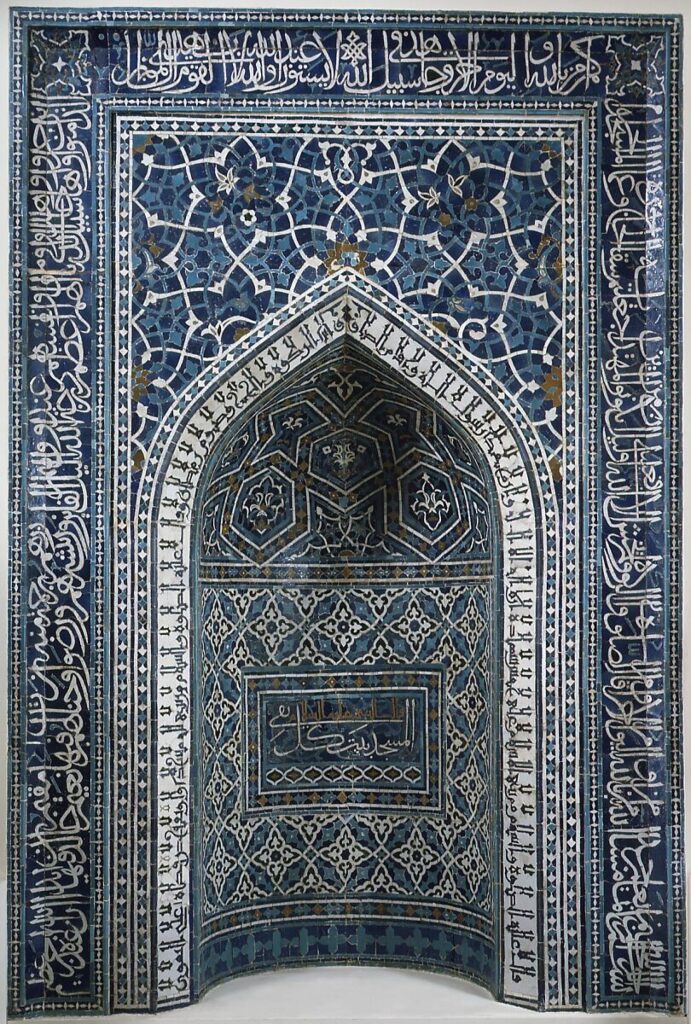

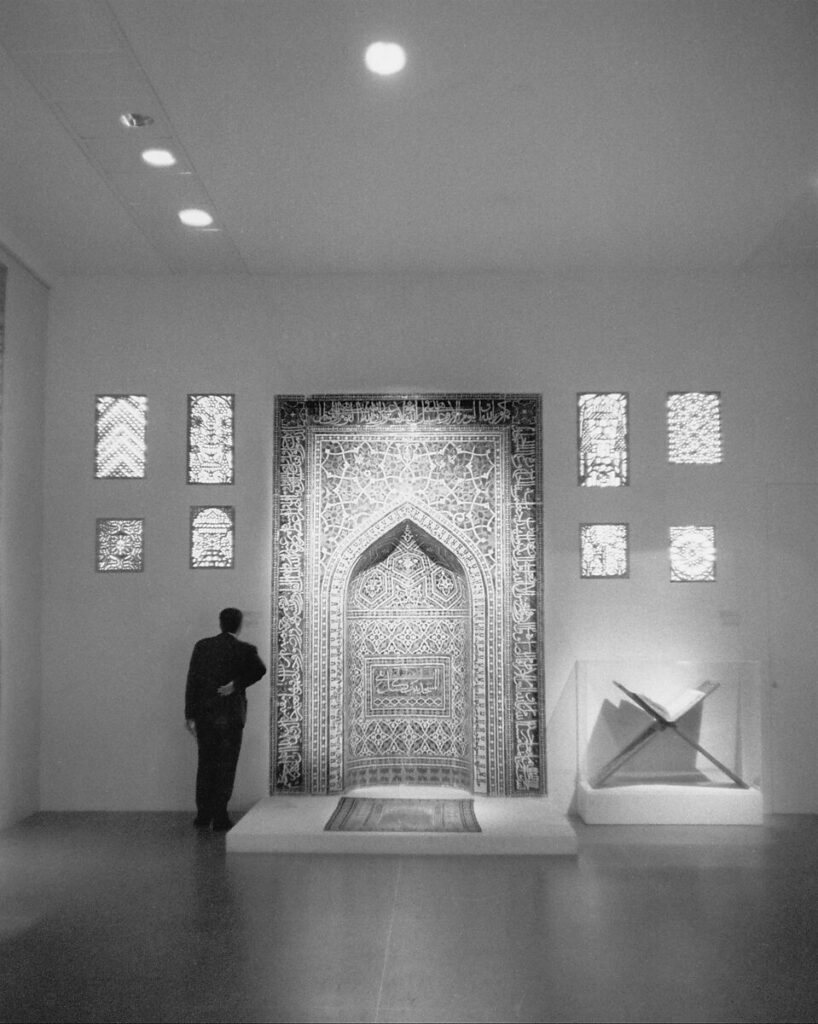

The Mihrab (Prayer Niche)

The mihrab, a niche that points toward Mecca, the Muslim holy city in Saudi Arabia, in which muslims face when praying, is the most crucial component of every Mosque. This illustration is from the Madrasa Imami in Isfahan and is made of a mosaic of tiny glazed tiles that have been pieced together to create a variety of designs and inscriptions. Verses from the Holy Qur’an span the outside frame from bottom right to bottom left.

Minbar Doors

One of the Museum’s first gifts was given by Edward C. Moore, a Tiffany and Co. designer who drew inspiration from Islamic art to create the minbar door. A minbar, or pulpit, is a podium that is accessible by steps and has doors similar to these at the bottom. Imams, or prayer leaders, utilize it at mosques when leading the Friday prayer, which is a sermon during the weekly gathering at noon on Friday. These doors, which include the elaborate geometric inlay typical of the Mamluk era, are believed to have originated from the Saif al-Din Qawsun Mosque in Cairo, which was built in the fourteenth century.

Tasbih Beads or Masbaha

These beads were discovered together but were later re-strung in a contemporary context, suggesting that they formerly belonged to a string of prayer beads. In Islam, prayer beads are strung with either thirty-three or ninety-nine beads to make it easier to recite the ninety-nine names of God. Three sets of beads, divided by two different beads (referred to as imams), as well as one bigger piece (referred to as the yad) that serves as the handle, make up a standard masbaha.

Check out Arab America’s blog here!