Gustavo Said: Syrian-Lebanese Immigrant Identification in Piauí, Brazil

Date/Time

Date(s) - 04/19/2023

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Location

The Lourdes Casal Project

Categories

Cost:

Free USD

Contact Person:

Email:

lourdescasalproject@gmail.com

Website:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/gustavo-said-syrian-lebanese-immigrant-identification-in-piaui-brazil-tickets-576143469627

Phone:

Organization:

The Lourdes Casal Project

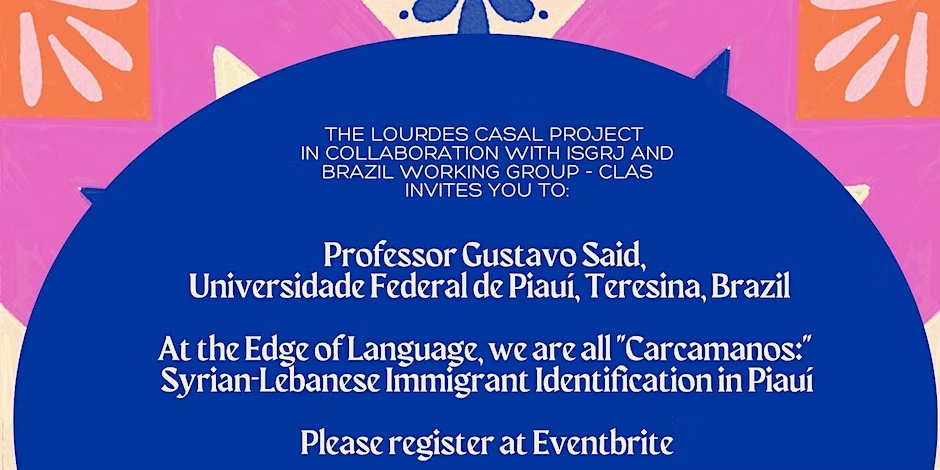

The Lourdes Casal Project, the Center for Latin American Studies – Brazil Working Group, the Chancellor’s Office, and Institute for the Study of Global Racial Justice invites you to a lecture by:

Prof. Gustavo Fortes Said: At the Edge of Language, we are all “Carcamanos:” Syrian-Lebanese Immigrant Identification in Piauí, Brazil.

Humanitarian Aid donations accepted for Earthquake victims in Syria and Turkey, 100% to be donated to UK-based not-for-profit, Action for Humanity.

Facing repression in the aftermath of the First World War, many Syrian and Lebanese minorities (in 1914, an estimated 300,000) left their homelands within the former Turkish Ottoman Empire in search of a ‘new world’. This lecture reflects on the immigration of Syrian and Lebanese to Piauí, Brazil, in the first decades of the 20th century, by highlighting the difficult process whereby Arabic-speakers inserted themselves into a New World cultural context.

In this violent reconfiguration, the linguistic matrix is the key to understand the modes of cultural integration. The Brazilian host culture both denied these migrants from Syria and Lebanon the right to speak the native language and, at the same time, required these Syrian-Lebanese migrants to express themselves nevertheless in Portuguese. Based on the life stories of his grandparents, both Syrian immigrants who left their homeland in the prelude to the First World War, Said demonstrates how, through the loss of their own language and the insertion into foreign languages, Syrian and Lebanese migrants came to be stereotyped and racialized with the Italian vernacular phrase (carca la mano). The resulting neologism in Portuguese (carcamano) denotes Arabic speakers pejoratively. This phonetic connection separated the Syrian-Lebanese community from its language and traditions and, at the same time, created a cultural reference that defined mutual recognition through the use of a discriminatory stigma: not Italians, not Brazilians, not really Arabs, Syrians or Lebanese, but Carcamanos. As a result, Arabic speakers, ironically, came to be identified, only in Piauí and nowhere else, by a referent linked to another immigrant group. The language, the speech of this group, despite pretentious literality, expresses a paradoxical situation: Syrians and Lebanese, who were mistaken for Turks because of the passport issued by the Ottoman authority, became ‘another foreigner’, the italian “carca la mano.” Since then, a subtle rhetorical operation promoted a spurious identification, and created a negative stereotype, that bears the weight of the genetic and racial determinisms prevalent at the dawn of the 20th century. From their anger at being confused with their (Turkish) oppressors, these Syrian-Lebanese migrants in Brazil began to live, by dint of a phonetic suggestion, with the general idea that every Arab trader was dishonest, a stigma they had to carry as a cursed family heritage, passed on for generations. Between smiles, they said, about the Syrians and Lebanese: “carca la mano, figlio” (from Italian to Portuguese, that means, in the language of the trade balance: “weigh your hand, son; stretch the measuring tape, son,” which is to say, “adulterate weight and length, son”. Based on this local analysis, Said measures the complex fabric of language that organizes his own identity and cultural inheritance. But this same “material” suggests that he will reach the end of the text without knowing who he really is. Alluding to the separation and distance he had from his grandparents since childhood, the essay ends by describing the experience of Arab otherness as crystallizing as a sign of an absence–the absence of the grandparents, and the lack of knowledge of their mother tongue. The essay adumbrates the gap in each personal history, the empty sign to be filled. Said asks: what ‘presences’ must we abandon? What ‘absences’ must we assimilate? To what extent does this history of Syrian-Lebanese migration to South America figure how arrivants more generally to this hemisphere are children of an ‘other carcamano’?

Gustavo Fortes Said (PhD in Communication Sciences from University of Vale of Rio dos Sinos) (2006) is Professor – at the undergraduate and graduate levels – at the Federal University of Piauí and sub-coordinator of the Master’s Program in Media Processes. Said was general coordinator of postgraduate studies at UFPI and the Interinstitutional Doctorate in Communication Sciences (UFPI/Unisinos). He has experience in the field of Communications and Media Studies, working mainly on the following subjects: imaginary, subjectivity, psychoanalysis, journalism, cultural studies, Arabic immigration to Brazil, media studies, and history of media in Piaui. He was a visiting professor at the Universities of Nebraska-Lincoln and Mississippi (Old Miss), in the United States. He won the Donald Brenner Best Paper Award, given by the ISSSS – International Society for the Scientific Study of Subjectivity, for research presented in 2013 in Amsterdam. Said is also the author of several books.