Essaouira: The Picture Postcard Moroccan City

By: Habeeb Salloum/Arab America Contributing Writer

A few centuries ago, Portuguese men of war pounding the Moroccan coast with their thundering guns while men stormed ashore to build seacoast citadels in the name of the cross was a common occurrence. Yet, as history proved, conversion to Christianity was not the invaders’ primary purpose. They came to gather bounty and slaves and, at the same time, control the trade flowing to the coast from the rich hinterland.

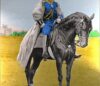

Moroccan armies led by illustrious sultans tried year after year to dislodge them until they gradually succeeded. One by one the Portuguese strongholds fell until these invaders were driven out from all the Moroccan coastlines.

Such is the history of Essaouira, one of Morocco’s loveliest towns. On the site where the Phoenicians had built a trading station, the Portuguese in the 16th century built a fortress city they called Mogador – a name derived from the Arabic amogdul, meaning safe harbour. The Moroccans tried a number of times to evict them, but they did not succeed until the powerful Sultan Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdallah in the 18th century captured the citadel. He then rased it to the ground to erase the memory of the Portuguese aggressors. ON its ruins, and according to plans drawn up by the captive French engineer Théodore Cornut, he built a town which he called Essaouira. The mosques, madrasas (Islamic schools) and ramparts one sees today almost all date from his era.

Historians do not agree as to what Essaouira means. Come indicate that the name is derived from the Arabic al-suwayra (small walled fortress). Others claim it is the Arabic al-soora (the picture). Probably, the latter is the correct derivation since coming in from the sea, the white town surrounded by reddish walls seems to rise out of the water – a jewel of enchantment, justifying the name, “a picture”.

The most attractive place on the Moroccan coast, it is well designed and architecturally beautiful. With its white-washed walls and bright blue shutters encased in a frame of medieval bastions and impressive pin-red ramparts, it is a charming and enticing town.

In the past dozen years, I had travelled a number of times through Essaouira on my way to Agadir from Casablanca. On each occasion, when I saw its blue-tinged white houses sparkling in the sunlight, I would resolve to return and explore the city. However, for years fate had decreed otherwise, until one day while enjoying the pleasures of Agadir, Morocco’s queen of resorts, I decided the time had come to make my long-delayed journey.

The January morning air was cool as our bus made its way northward form Agadir. Hugging the Atlantic coast and edged by shrub covered hills, the highway gave us a fine view of the beaches being pounded by the ocean waves. We passed the road leading up to Immouzer which is noted for its waterfalls, then on through Tarhazout choked with trailer camps. Here, many Europeans have come for years to spend their winters in southern Morocco’s mild, pleasant climate

As we drove further on, the countryside appeared to be very poor. The inhabitants of the few villages along the way eked out their living from tiny stone-filled plots of land. The only income-giving crops we could see were the odd field of bananas – a fruit only cultivated in this part of southern Morocco.

Beyond Tamri, a banana growing town, the foothills of the High Atlas became progressively more prosperous. The further north we travelled the more trees, mainly argan, we saw. A forest of argan 25 miles wide and 94 miles long, runs parallel to the ocean between Essaouira and Agadir. It is the largest argan forest in the world. This tree for some unknown reason only grows in Morocco and Mexico.

In Morocco, goats thrive on its foliage and the fruit is pressed for its oil. On the other hand, in Mexico, only the wood is utilized. No one has yet discovered that its fruit produces a fine cooking oil.

At Tamanar, about 44 miles before reaching Essaouira, we stopped for coffee. Unable to converse with any of my fellow passengers who spoke only French and German, I sought the guide who was having his breakfast. With true Arab hospitality, he offered to share his meal with me. Although I was intrigued with what he was eating, I politely refused. Nevertheless, after some persuading, I agreed, anxious to discuss the dish he was having for breakfast.

During my two and a half months stay in Morocco, I often wondered what the inhabitants had for breakfast before the French occupied their land. Rarely could I find anything to eat for the first meal of the day except croissants. Now as I dipped a piece of bread into a mixture of honey, pulverized almonds, and oil, I found that the Moroccans, indeed, have their own breakfast dishes. According to our knowledgeable guide, Hafid Souili, this was only one of the traditional tasty early morning foods. However, he had no answer as to why croissants in their various forms were the only breakfast food served in the public eating places.

It is apparent the Moroccans do not know that this pastry was invented in Vienna in the 17th century after the Austrians had defeated the Turks. The eating of the croissant represented a symbolic gesture of consuming the Muslim crescent. Though often denied, the tentacles of colonialism come in more ways than one.

About a dozen miles before reaching Essaouira, the land flattened and the argan trees thickened into a dense forest. Ahead we could clearly see the towering unfished minaret of a mosque and school which is to become the Institute of Islamic Law. A few miles further on, Essaouira loomed before us, its white structures glittering in the sunlight – a postcard picture of beauty.

The city built on a low-sandy-narrow peninsula is a pleasant bright beach and fishing town. Its main attraction is its lively Madina which includes the old Jewish Mellah, the section where 2,500 Jews once lived. Today, only 20 remain. The remainder left for Israel after the creation of the Jewish state.

This older part of Essaouira is full of arched souk (market) stalls, indigo tiled fountains, and flowerbeds, making for colourful streets. These narrow alleyways are overshadowed by the picturesque white buildings dotted with blue – a type of structure introduced by the fleeing Spanish Muslims and to be found in many parts of North Africa. Unlike the majority of towns in Morocco these streets are rectilinear and always kept clean.

The most important landmarks in the city are its two bastions. One of the fortresses, Port Scala, an 18th century crenelated stronghold, with its old bronze Spanish cannons, overlooks the fishing port. From its walled fortifications there is a magnificent view of the harbour, beach, and offshore islands. In its tower, Orson Wells filmed his famous Othello. The other fortress, Kasba Scala with its crenelated façade looking seaward, is a raised platform almost 656 feet long with a battery of Catalan bronze cannons. As if to protect it further, around its ocean sides, volcanic rock poke jaggedly out of the foaming waves.

Along the sea front are charming gardens of mimosas and palms and a two-mile-long beach – a crescent of white sand. The gentle breezes and warm waters washing its edges makes possible year-round swimming.

We started our tour by passing through the Marine Gate erected in 769 during the reign of Sidi Mohammed Ben Abdallah. The fish auction was our first stop. We watched dozens of types of fish being sold, then lingered on the outside to sample at the cost of a few cents, the mouth-watering fresh fish being barbecued.

Like all tourists, we visited the two fortresses, then plunged on Rue Mohammed Ben Abdallah into the heart of the Median. A mass of humanity seemed to be everywhere. Men and women dressed in traditional clothing were intermixed with others decked in the most modern costumes of the 20th century. Surprisingly, scattered among them were a fair number of foreign tourists. It was a colourful mixture of the past and modern worlds.

From this dense movement of humanity, we strolled through enticing aromas of barbecued meat to the carpenters’ quarters below Kasba Scala. In tiny, vaulted caverns lining the inside of the ramparts, skilled woodworkers were carrying on centuries-old traditions. In their sem-dark shops they were polishing the hard thuya wood to a satin finish, then inlaying it with cedar, lemon wood, ebony, mother-of-pearl, and silver in exquisite floral and geometric patterns. Superb tables, trays, chess sets, and boxes of all kinds were in the process of being inlaid or lined the shelves of their tiny workshops.

The craftsmen bring out the subtleties of the thuya wood by using the veneers of the same wood in a checkered design, or with chevrons, stars and other forms in mother-of-pearl, ebony, and silver. It is said that the wood artisans of Essaouira combine and harmonize their inlaying to sing a song of beauty.

Nearby we stopped to watch craftsmen fashioning silver jewellery and daggers. Their well-made products are to be found not only in Essaouira but in many other towns in Morocco. Also, in this glittering city some of the finest worked gold jewellery in Morocco is manufactured. Two skilled master goldsmiths: Abdallah Assfaouine and Nissim Loeub have preserved the secrets of the ancient traditions of Essaouira’s handmade gold products. With hands inheriting the skills of centuries, they fashion delicate gold ornaments, much sought after by the affluent of Morocco.

We left the artisans at their tasks and walked a few hundred feet to Moulay Hassan Square to rest and have a cup of delightful Moroccan mint tea. Refreshed, we walked on the outside of the ramparts to photograph the Portuguese clock tower set in the walls.

From the clock, it was only a few hundred feet to the Hotel des Iles where we were to dine. The most luxurious lodging place in the city, it edges the beach and has a fine view of the ocean beyond.

Resting around the swimming pool after lunch, I though of enchanting Essaouira, a tiny resort counting no more than 40,000 souls. With its soft sandy beaches, handsome buildings, and romantic historic fortifications, it is an ideal place to rest after the nerve-taxing Moroccan metropoles of the north. Unlike industrial towns, there is no pollution to mar its clear air. Almost all the inhabitants make their living by fishing, handicrafts and, of course, tourism.

For a few years in the late sixties and early seventies, the city became known as a hippie town. A mass of young people from all over the world came and settled for a while in this dream town. The sunshine, sandy beaches, beauty of the city and cheap prices drew them like a magnet. However, with the demise of the hippie movement in the West, their numbers in Essaouira gradually faded away until they became only a memory.

The hippies have left but other tourists still come and are enthralled with this resort which to Moroccans is a small insignificant town. they have a saying that ‘five francs of incense is enough to perfume the whole city’.

Notwithstanding this belittlement, for travellers it is a different story. Tourists who yean for a restful holiday can do no better than spend a few days in this splendid Moroccan resort. Here, they will come to know the meaning of relaxation.