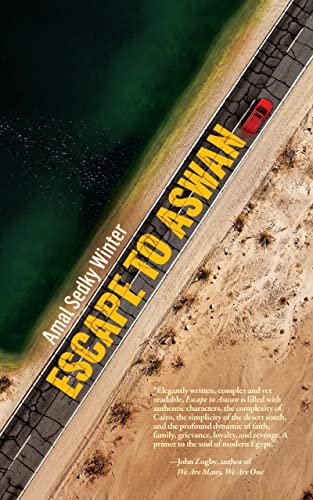

Escape to Aswan - A Review

By Alison Norquist / Arab America Contributing Writer

Following the events over a five-day trip to Cairo, Egypt, Amal Sedky Winter weaves a gripping tale of political intrigue and human emotion that is impossible to put down. Set throughout the country of Egypt in the fall of 2014, the world that surrounds the story is inescapably real. As three people, put in an extraordinary position, must make choices that will forever change the course of the other’s lives, the continuing unrest of Egypt roils around them.

A Synopsis

Coming Home

Anyone who has ever had to deal with changes in plans, airports, and international visas will be well acquainted with the opening to Sedky Winter’s debut novel. Salma, a nearly 40-something single mother of two, travels to Cairo for a conference. While she is a dual citizen, there is a stark contrast in her ability to move about the country compared to the others who must go through the various lanes of international travel. While she is a citizen, a well-connected one at that, she does not have the proper documents to enter the country without a hiccup. While she is normally escorted out of the airport by her cousin, he is inexplicably nowhere to be found. What’s worse, the country is on high alert following riots and continued political upheaval.

The Stories

After being detained by “idiotic bureaucrats,” Salma is rescued by her father, Hani Hamdi, the Department of Military Medicine’s head. A cold man, who has grown colder with age and distance from his daughter, he berates her for her lack of Egyptian documents, being divorced, and not living in her home country. As they travel several hours to their home, which is only across the city of Cairo, a third attempt is made on Salma’s father’s life. A truck drives into the procession of limos escorting the family from the airport, resulting in a shootout between Hani’s men and the unarmed driver. Once they resume their journey, Salma learns of the fictional, but realistic Taj al Islam, a radical Islamist militant group that is vying for power.

Meanwhile, Salma’s fiance and colleague, Paul Hays, is covering a protest that is turning violent in Tahrir Square. A Jewish-American journalist on assignment for Harper’s, Paul is one of the industry’s foremost journalists for covering politically turbulent countries, having already worked in Egypt and Iraq during wartime. But as he is covering the protest, a masked man attacks, trying to kidnap him. Paul escapes the attempt battered and bruised, but misses his meeting arranged by Israel’s Mossad to retrieve an important package regarding the little-known Taj.

The third string of the narrative is Murad, a young man who has been working for the Taj since a former lover jilted him during his time at school in America. The woman, a then-graduate student, rejected his proposal of marriage after their brief affair, which clashed with his deep-seated sense of traditional values. Since then, he has been the right-hand man for Nabulsi, Taj’s head. But when the woman he still deeply loves turns out to be a target for kidnapping by the Taj, a plan begins for Murad that will test his love for her.

Fight and Flight

As Nabulsi’s sworn enemy, Hani is frightened for his daughter’s safety while she is in the country. Her attendance at a conference is halted when she is kidnapped by the Taj. Her captor, a merciless man named Amin, forces her into a car. The driver, a man whose voice Salma once knew so well, puzzles her as she is driven through the city, being battered by the rough roads and cluttered floor of the back seat upon which she is laying.

After arriving at a safe house, Amin is told by the driver to go inside to tell Nabulsi that Salma is here and bring out a rug to smuggle her into the building with. As soon as Amin is inside, Murad speeds off into the night with Salma. He informs her of his plan to leave the Taj, with her as his bargaining chip hoping that Hani will be able to save him once he returns Salma to him. Taking her out of Cairo, Murad brings her from the safe, upper-class world that she has always known in Egypt to the rural communities of the Upper Nile. Here, she is cared for by his family in a rural medical clinic and shown what true Egyptian life is like: full of starvation, poverty, and desperation.

Meanwhile, Paul is doing everything he can to get the love of his life back. He travels around the city trying to find a way to connect with the Taj, hoping to find a way to bargain the special package he intercepted from them when he arrives in the city. Brought to the edge of sanity in a war between Hani’s forces, Taj’s merciless men, and Israel’s Mossad agent, Paul must make an impossible decision to save Salma.

The Women of Egypt

In this incredible debut, Amal Sedky Winter creates a brilliant tale focusing not just on the prolific corruption and poverty of Egypt, but also on the resilience and kindness that the women of Egypt embody. Throughout Salma’s journey along the Nile, she encounters stunning women who are making the best of what little they have been afforded in life.

The woman of rural communities, who Salma expresses later to her father, would sooner feed her as a guest than save what precious little they have for themselves. This rings true as Salma arrives in Sidi Osman with Murad’s mother, an elderly woman who has had a hard life and has even harder soles on her feet. The women there, visibly malnourished and starving, offer Salma dates during their brief encounter, hoping in return that she will give their village valuable medicine like aspirin and antibiotics.

Om Mohamed, a woman who defines herself only as a mother, carries the name of her dead first son despite the fact that she has her own name to go by. It is her love for her children that ultimately saves Salma. Murad’s sister, the village doctor, is faced with not only the typical daily problems of medicine but also tries to educate the women of the area about how dangerous circumcision is for their daughters. When a young girl, no older than 12, is brought in with a severe infection from the banned ritual, instead of giving a gentle bedside manner to the mother, she berates her in a way that is only too similar to the ferocity a mother would scold her child for doing something that would hurt them. But still, she sits with the child overnight, tending to her around the clock.

The novel also does an excellent job of portraying the duality of the patriarchy in Egypt. During her hiding in various places during her journey, it is the abaya and burqa that save her from being found by Nabulsi’s men and the strict religious laws that prevent men from being with women in a mosque that allows for her safety in a village whose nearly entire young male population is involved in the Taj. The women, removed from safety just by being near her, are ultimately the ones that provide her the safety and strength to carry on.

Best of all, the women are not depicted in a way that would be a caricature or exacerbated depiction of their grueling lives. Instead, they are portrayed with grace, love, and honesty that is rarely afforded to deeply religious women. They exist alongside their religion, not as a portrait of it. This is true even of Mariam, a Coptic Christian woman who takes Salma in despite her burqa signaling that she is a devout Muslim. Escape to Aswan is ultimately a love letter to the women of Egypt, portraying their diversity and resilience but in a way that does not fetishize their pain as so much Western media does to women in similar circumstances.

Escape to Aswan will be released on April 18th, 2023.

About the Author

Like the protagonist in The Second Veil, Amal Sedky Winter is a strong, bi-cultural, Egyptian American woman with a foot in both worlds. Her life experience and training and work as a psychologist enable her to compare and contrast them from both inside and outside both cultures.

Sedky Winter’s professional experience includes being a clinical psychologist in private practice, a court appointed evaluator, mediator and special master, and a professor in three graduate programs that she helped establish—the last being at the American University in Cairo to which she bi-located from Seattle for seven years.