Egyptian Life Reveals Itself on Cairo’s Metro

By: Habeeb Salloum/Arab America Contributing Writer

On my first day in Cairo, Adel, my taxi driver, was taking me to the heart of the city through what must be one of the most congested traffic in the world. Noting that the autos would squeeze into any empty space yet still not make much headway, I asked, “How can you drive in this city?” He smiled, “It’s a way of life for us. For a visitor like you, I suggest the Metro.” In the ensuing days, I was to regret that only belatedly did I remember his advice.

For a week, I explored both the new and the historic sections of the city, but it was a nerve-wracking affair. Autos did not follow any traffic rules, darting back and forth across lanes and inches in front of other vehicles. In between, buses, always loaded to the hilt, made their way with great difficulty.

In this chaotic traffic, taxis in the thousands competed for space. The drivers, veterans of this turbulent daily spectacle, were always on the lookout for European and North American tourists or, second best, Arabs from the Gulf. Only lastly would they consider their fellow Egyptians as potential customers. The taxis all had metres but these are never used. From what I could make out, the foreigners, especially if they do not bargain, are charged four times the going price; Arabs half; and, of course, the inhabitants are familiar with the rates.

One day I surprised myself when, amid this world of pandemonium and bargaining, I remembered Adel’s suggestion that I should move about the city by Metro.

After paying a fare of a few cents, I placed my ticket in a modern turnstile, then walked into an up-to-date subway station, leaving behind the noise and nightmarish traffic jams of the city above. For virtually the same price as squeezing into a bus, I would travel in peace and quiet – so I hoped as I stood waiting on the platform.

In a few seconds, a train stopped and the coach doors opened. After entering, I looked around. All the passengers were muhajjabeen (dressed in Islamic fashion) women and some children. “Where were the men?” I thought to myself. Momentarily, I had a feeling of panic as I watched the women staring at me.

Looking down, I noted a boy of perhaps six watching me with a faint smile on his face. I am sure I was blushing when I asked, “Why am I the only man in this coach?” “It’s for women only. Get off at the next station.” The boy had a devilish grin, no doubt enjoying my predicament.

For the next few minutes I felt the discomfort blacks must have experienced in America’s south, earlier in the last century, when they found themselves in a ‘whites only’ section of a bus.

Quickly stepping out of the coach at the next stop, I felt a sense of relief. I never would have thought that some 50 staring women would make me so uncomfortable.

When reality returned, I asked a well-dressed young man, “How does one know which are the women’s coaches?” He looked at me inquisitively with a twinkle in his eye. “Don’t you know? You must be a stranger! It’s always the first two coaches.” Having learnt my morning lesson, I waited for the next train.

Unlike those of the women, the men’s coaches – women in western dress also ride them – were crowded with many passengers standing. A teenager seeing me squeezed in a corner offered me his seat. I smiled and politely refused. However, he insisted and stood up, motioning me to sit down.

Like this youth, most Egyptians are very courteous and helpful to their elders and strangers. Even though the vast majority are very poor by western standards, with the exception of the few who hang around tourist establishments, they do not seem to resent affluent western visitors. The people with whom I talked attribute this lack of envy to Islam and its teachings.

This could be very well the case. I do not know if it was my speaking in Arabic or the devoutness of the people, but during my month’s stay in Egypt the ordinary people always treated me with kindness and respect. Never seemingly upset, they always quote the phrases: insh’a Allah (if God wills); ma’aleesh (it dosen’t matter); and bukra (tomorrow).

No sooner had I settled down then a middle-aged man sitting beside me began to recite verses from the Koran, looking straight ahead as if in a trance. On and on he went until I reached my destination, Sadat Station, in the heart of Cairo.

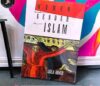

In my travels throughout the Arab world, I have never seen people so devoutly religious as the Egyptians. More than once, I noted that taxi drivers, when passing historic mosques, would bless the name of their builders. To a stranger, it appears that the whole country is living in religious fervour.

It is said that, for the people of the Nile Valley, nothing has changed since the pharaohs built the pyramids. The ancient Egyptians spent half their lives building temples and tombs dedicated to the gods; after Christianity, masses of men spent their lives praying in desert monasteries; and when Islam came, for some 1000 years, Al-Azhar, the world’s first university, has continually sent men all over the world to teach the tenets of Islam.

A minute after I stepped out of the coach at Sadat Station, I stopped an older man dressed in a galabiya (traditional Egyptian dress), asking him how to get to Tahrir Square. “It’s here! Overhead!” He pointed upwards then continued, “You must be a visitor! Welcome to our country, as we Egyptians say, ‘the mother of the world’.”

A few days later, on the plane returning to Canada, I met a U.S. couple that had travelled for a month on a shoe-string budget throughout the country, enjoying Egyptian hospitality. Gail, the young lady, expressed it all when she commented, “The people of Egypt are very kind and gracious. They made our vacation a joyful event.”

Back on the street, I was again in the world of pollution and bargaining above nerve-shattering noises. It was the timeless Cairo of Egypt that one can explore by riding the tranquil Metro – still being expanded.