By Ali Gharib

The Nation

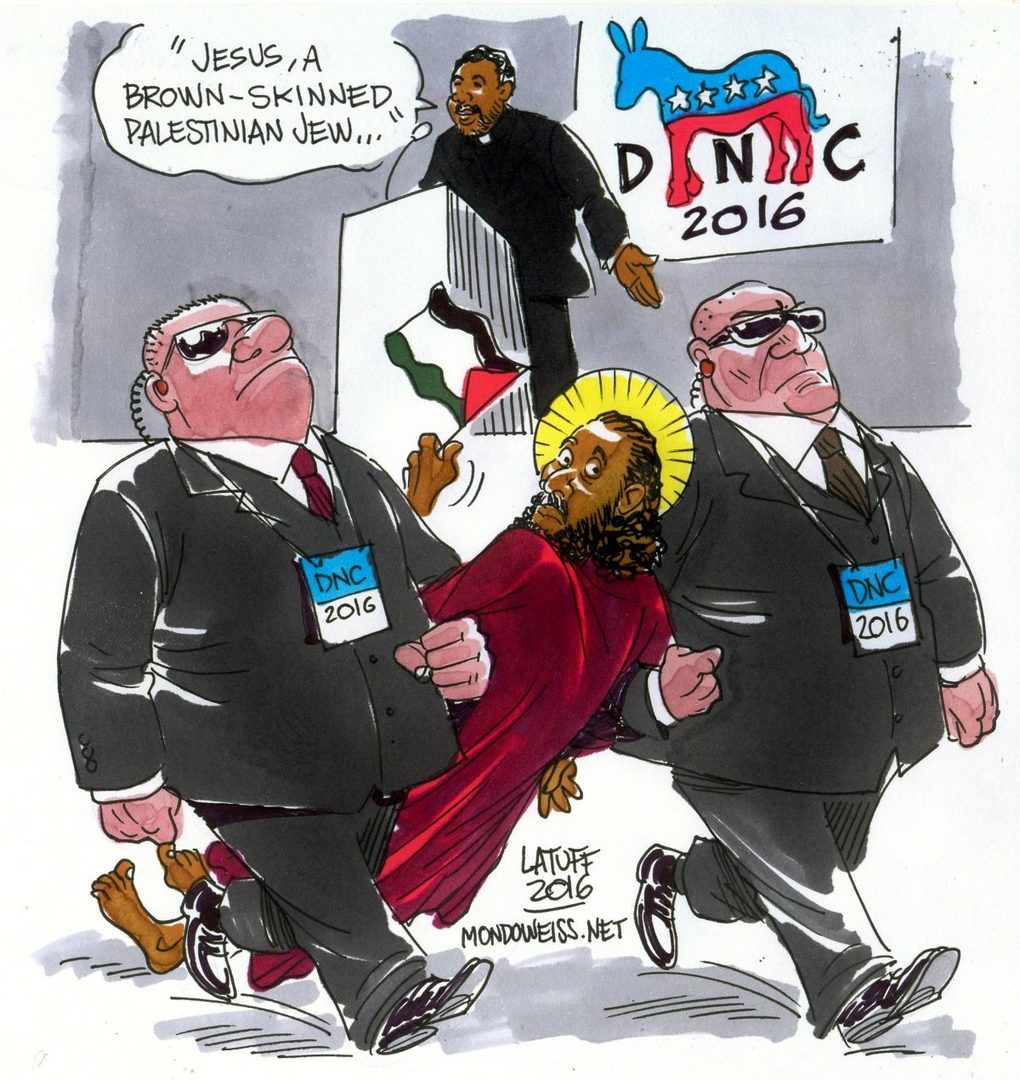

On Monday in Philadelphia, the Democrats ratified what Hillary Clinton’s website touted as “the most progressive platform in party history.” On several issues—the minimum wage and trade, for example—the platform took positions closer to those espoused by Clinton’s erstwhile primary rival, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders. On a few issues, though, Clinton’s campaign dictated a platform that took more moderate positions. One was the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: the document doesn’t mention Israel’s occupation or its settlements. That was in line with Clinton’s position: Throughout the Democratic primary, she has made a point of trying to mend fences with right-wing Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu by eschewing any criticisms of Israel whatsoever.

Arriving at the final platform was a long journey, during which Clinton’s delegates had to beat back challenges on her pro-Israel orthodoxies over and over again. During the past two months Democrats gathered three times to set the platform, first to hear testimony from witnesses chosen by the campaigns, then twice to flesh out the platform before passing a draft on to this week’s Democratic National Committee. At the second session, in late June in St. Louis, a month before the convention, the platform committee sat through a series of lengthy debates. It was past one in the morning before Israel came up and the last proposed amendment—to the language about the Mideast conflict—was read aloud.

In the two paragraphs of the platform dealing with Israel, the document called for supporting Israel and pushing for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. James Zogby, the head of the Arab American Institute and a longtime party activist, read aloud a proposed amendment in an unmistakably Midwest accent. Zogby wanted to add language that would explicitly mention Israel’s occupation and strip out the platform’s condemnation of the movement to boycott, divest from, and sanction Israel (BDS).

“We didn’t recognize a Palestinian state in our platform until 2004, after George Bush did it,” Zogby said during the debate. “We have an opportunity here to send a message to the world, to the Arab world, to the Israeli people, to the Palestinian people, and to all of America: that America hears the cries of both sides, that America wants to actually move people toward a real peace.”

“The term ‘occupation’ shouldn’t be controversial,” Zogby, a Lebanese-American, added. “If our policy says it’s an occupation and settlements are wrong and they inhibit peace, why can’t our politics say it? It doesn’t make sense!”

Zogby mentioned several times that the proposed changes had come from Bernie Sanders himself. Sanders began his campaign avoiding foreign policy altogether, but eventually became more outspoken on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, taking Netanyahu to task not only for the Israeli settlement project and continued occupation but also for Israel’s conduct of the 2014 war against the besieged Gaza Strip.

The move was a natural one for Sanders. These days, criticisms of Israel are issued among not only from the left-wing of the Democratic Party, but much of its base. American liberals have become disenchanted with Israel as its occupation becomes more permanent. Then the Israeli government led a fight against the Obama administration’s Iran nuclear deal with a misinformation campaign that saw denunciations of Netanyahu among Democratic members of Congress—once a stronghold of unconditional support for Israel. As a result, Pew polls show a consistent trend of liberal Democrats shedding their unquestioning support for the Jewish state.

Like on the minimum wage, Sanders stood at the vanguard of a widespread emerging progressive sentiment. Now his delegates to the platform committee would be doing battle—civil, though it was—with Clinton’s delegates over one of Washington’s most contentious issues. In the end, it would be Sanders who would make decisions of how hard to press the debate. Party activists and progressive Democrats wondered if the candidate would take the fight all the way to the convention floor.

* * *

Stirrings of a debate over Israel-Palestine in the platform had become apparent as Sanders and Clinton each announced their delegates to the committee; Sanders got five positions and Clinton six. Among Sanders’s picks were Zogby, with his long record of advocating for pro-Palestinian causes, and Cornel West, the loquacious left-wing academic who has advocated for the controversial BDS movement. On Clinton’s side, a medley of more establishment delegates—among them Ambassador Wendy Sherman, a former undersecretary of state and Clinton campaign surrogate, and Neera Tanden, the president of the Center for American Progress (where I used to work), which has played a role in Clinton’s play to mend fences with Netanyahu and Israel.

The Clinton campaign’s delegates to the platform committee and its witness to the hearings held firm on this stance. Asked by West, Robert Wexler, a former congressman called to testify before the committee before the platform’s drafting, said the document should not refer to “what you refer to as occupation”—let alone settlements.

At the drafting hearing, the issue would reemerge. Zogby read aloud the initial plank calling for a two-state solution. “Here we add our language,” he said, proposing his amendment to insert a call for “an end to occupation and illegal settlements.”

BDS also came up. Initially dismissed by pro-Israel forces, now that BDS is a burgeoning grassroots movement, pro-Israel advocates speak of it in apocalyptic terms—often equating the peaceful activism with the violent terrorism faced by Israelis. Sanders hasn’t endorsed the BDS movement, nor has he condemned it. Clinton, on the other hand, has made a point to attack the movement: in a letter to her top funder, the Israeli-American businessman and philanthropist Haim Saban, Clinton proclaimed BDS “counterproductive” and vowed to advocate against it. The promise was fulfilled in the platform draft. The Democratic Party committed itself to “oppose any effort to delegitimize Israel, including at the United Nations or through the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement.”

Zogby’s amendment sought to strip the language out. “They were pretty damn insistent on it,” he told The Nation of the Clinton campaign’s efforts to keep the plank. “It was gratuitous, is what it was. You wanna say we oppose efforts to delegitimize Israel? Go ahead and say it. I personally think Netanyahu does more to delegitimize Israel than anybody, but go ahead.”

At the drafting hearing, the Clinton campaign defended the inclusion of the anti-BDS plank. “I think the drafters were very careful here not to say outright we oppose BDS, but basically to say if, in fact, there is a delegitimization of Israel through BDS,” said Sherman at the hearing, “this is not a good thing for anyone.”

What was supposed to be a 16-minute debate about Zogby’s amended language turned into more than a half an hour of back and forth. Committee members stated their support for and opposition to the amendment as Representative Elijah Cummings, the committee chair, allocated minutes.

As the debate went on, Zogby brought up 1988—when he had also tussled with Wendy Sherman, who worked for the Dukakis campaign. “I remember being in this same situation with Wendy Sherman in 1988,” he told the committee, “when we called for mutual recognition, territorial compromise and self-determination for both people.”

Sherman acknowledged the shared history: “Jim is right,” she said. “He and I haven’t grown any older since 1988 when we tread this same territory.”

* * *

The Democrats’ 1988 debate over the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in fact tread a very different territory. In 1987, Palestinians had risen up in the First Intifada, overwhelming peaceful organizing against the occupation that was met by Israel’s overwhelming military force. As the 1988 conventions approached, consciousness of the Palestinians’ plight was growing among Americans. Thanks to a campaign organized by, among others, Zogby’s Arab American Institute, seven state Democratic Parties endorsed Palestinian self-determination. The moves became a source of worry for pro-Israel lobbyists. “We’re deeply troubled,” an American Jewish Committee official said at the time, “by any outcropping of the kinds of views we are seeing in some of these states. But I am confident they do not reflect American opinion in general, nor the mainstream of the Democratic Party.”

In 1988, Zogby was acting as a delegate for another progressive primary insurgent, Jesse Jackson. By the time of the convention, Jackson’s campaign had long since lost its race for the nomination, but his supporters and delegates sought to infuse the Democratic Party with the left-leaning vigor that spurred Jackson’s unprecedented run. Zogby, who then as now served on the platform committee, wanted to have the Democratic Party recognize the Palestinians as a people with basic rights. At the time, even such a basic proclamation was controversial, and inserting the language into the party platform would be an uphill battle.

Some party elites bristled at the notion that the Jackson campaign would seek to introduce a pro-Palestinian plank. “Although such a proposal would have no chance of being included in the platform,” reported The Chicago Tribune, “the mere possibility that it might be discussed disturbs many Democrats. ‘It would be bad,’ said a party leader. ‘Rhetoric would be unleashed which Republicans would like to dine out on.’”

As the platform committee met, Zogby fought to include language endorsing “self-determination” for the Palestinians. It was to be a call for a two-state solution: mutual recognition between Israelis and Palestinians. But the effort faltered: the plank was “debated by the committee and defeated without rancor,” reported The Chicago Tribune. Zogby and his allies in the Jackson campaign were determined to press on: they gathered enough signatures to introduce a minority plank to the platform at the convention in Atlanta later that summer. “That was the main platform fight in ‘88, the Israeli issue,” said Gov. Bill Richardson, who served on the platform committee. “You want to avoid a platform floor fight as much as possible,” he added, because independent voters and media pay closer attention once the conventions roll around.

Zogby suspected he had many Democratic delegates behind him. According to a Los Angeles Times/CNN survey released in July 1988, nearly two-thirds of Dukakis’s delegates supported “giving the Palestinians a homeland in the occupied territories of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.” Of Jackson delegates, 90 percent supported the notion. But the results were inconsistent: An Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll of delegates found that a narrow majority opposed endorsing a Palestinian State. What’s more, anonymous survey results don’t always transfer over to votes made in public.

Those who wanted to amend the platform feared that even some Jackson delegates might not end up voting for the plank. A compromise was brokered: Jackson gave Zogby his blessing to introduce the language and have it debated on the floor, but the amendment would be withdrawn before a vote was taken.

Though there would be no vote, a spirited debate ensued. Zogby read aloud his plank and was met by vociferous opposition. New York Senator Chuck Schumer, then in the House, condemned the plank. Daniel Inouye, a senator from Hawaii known for strong pro-Israel views, called it “a vicious kick in the teeth of America’s interests in that part of the world.” Both Schumer and Inouye were booed by convention delegates.

“The tensions were very high about Middle East policy,” Jesse Jackson told The Nation, recalling the fight in a June interview. “We felt it was the peoples both fighting for a state. And we had to go from a ‘no talk’ policy to a ‘let’s talk’ policy.”

The conversation over Palestinian self-determination had broken new ground for the party. “[O]nly a few years ago, even to discuss an idea so contrary to U.S. policy and to Israel’s view of security would have been unimaginable,” a New York Times editorial proclaimed. Zogby, remarking on the convention floor, said, “The deadly silence that submerged the issue of Palestinian rights has been shattered.”

Though no pro-Palestinian plank would end up on the platform, Jackson’s policy of “let’s talk” would soon become official American policy—and even led to a breakthrough. Though to this day no Palestinian state exists and Israel’s occupation has become more entrenched, a peace process toward a two-state solution was begun just three years after the 1988 fight when, at the Madrid Conference, Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization began unofficial talks. A year later, following a round of secret talks between Israel and the Palestinians, Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat shook hands on the White House lawn, presided over by Bill Clinton, to mark the Oslo Accords—a peace deal that yielded, if not a state, the mutual recognition between the two people Jackson’s delegates had called for.

Bill Richardson said Jackson delegates like Zogby helped bring the party along to the two-state solution. “I think they launched a useful effort that led to that historic handshake,” recalled Richardson, who along with Zogby and other figures in the 1988 fight was on the White House lawn that day.

“I didn’t feel vindicated,” Jackson said, recalling the Oslo Accords. “What happened that day could have happened years before.”

* * *

In St. Louis last month, as the early hours of Saturday morning ticked away, Elijah Cummings finally called a vote on Zogby’s Israel amendment. “It was pretty clear how it was going to go down,” one committee member recalled to The Nation. Throughout the long day, string of lopsided vote tallies had beaten back progressive efforts to get planks in the platform that took aggressive stances on trade, wages and climate change.

The amendment fell by an eight-to-five vote. “It stung,” the committee member said.

In Orlando on July 9, as the full 187-member platform committee gathered to make the additional changes to and approve the 2016 Democratic platform, party activists took another shot. Maya Berry, the executive director of the Arab American Institute, introduced two amendments to the platform that followed on the same changes Zogby had tried to make in St. Louis: one calling for an end to settlements and occupation and another calling for rebuilding the Gaza Strip. Berry and Cornel West gave impassioned speeches, followed by Clinton supporters opposing the additions. Neither amendment passed.

Still, Zogby is not entirely despondent. “Last time we were just trying to get Palestinians recognized as an entity,” Zogby told The Nation. “They wouldn’t let me use the ‘P-word’”—Palestinian—“in the platform. This time we were talking about occupation and settlements and the suffering of people in Gaza. It was a much richer discussion than we had last time.”

The draft language in the 2016 platform, for the first time, spoke of a Palestinian self-determination not just for the sake of Israel’s security, calling for a solution that provides the Palestinians with “independence, sovereignty, and dignity.” Some members of the platform committee lauded the addition. “The language in the platform is different from what it was on 2012, a little more balanced,” a second committee member said. “My view is that it sets us in a more progressive direction than four years ago.”

Other figures from the 1988 fight, however, were less sanguine. Asked whether he thought the Democratic Party had changed on Israel-Palestine issues, Jesse Jackson demurred. “Not very much. Not very much,” he said. “There’s no winners until there’s a resolution.” Jackson went on, “There’s no other nation in the world that could play the broker role. But we’re not inclined to play it. The very term ‘fair’ was put off limits.”

As it was when, 28 years ago, he introduced a minority plank that would never get voted on, Zogby understood his odds were more than long. “I knew we wouldn’t win, so there’s no ‘disheartening’ to it,” he responded when asked if he was upset at the loss. Like many amendments to the draft platform introduced by Sanders delegates, Zogby went into the platform debate without the votes to carry the day. Other similarities with the 1988 fight persisted: “The intensity, the nervousness of the other side was about the same. They didn’t want it debated then, they don’t want it debated now.”

When he was pushing for Palestinian rights in 1988, Zogby sought and received permission from Jackson to push the minority plank at the platform on the convention floor. In the runup to the convention in Philadelphia, Democratic and pro-Palestinian activists spoke of the possibility of pressing forward against Clinton’s mealy-mouthed platform. But on July 11, Sanders endorsed Clinton, ending his run for the Democratic nomination, and his campaign from there forward sought to avoid a confrontation. “It is not easy to introduce a minority plank without the campaign’s blessing,” Zogby told The Nation. “But then Bernie decided not to go forward.”

“I would have preferred to continue the debate as a minority plank,” Zogby went on, “both because it gives the issue much deserved exposure and would provide Bernie with greater leverage enabling him to press for structural reforms. At the same time, I’m going to respect that Bernie didn’t want to continue. I can only imagine the pressure to which he was subjected and the exhaustion he must feel.”

Clinton’s moderate tack on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict had finally prevailed among her party. With the Clinton’s Democratic Party shying away from so much as mild criticisms of Israel—even avoiding basic truths about the conflict—liberals who focus on the Middle East are left wondering whether, if she can prevail over Donald Trump in the general election, Clinton will stand up for liberal values and Palestinian rights.

Source: www.thenation.com