By Abigail Hauslohner

The Washington Post

Farooq Mitha’s friends, seated in a tight circle at a mosque here on a recent evening, told it to him straight.

“This would be the easiest election to take Muslims for granted,” said Mohammad Mubarak, a lawyer, as several of the other Muslim American political activists nodded.

The prospect of a Donald Trump presidency may frighten plenty of Muslim voters, the group told Mitha, but Hillary Clinton isn’t particularly popular, either. In the Democratic primary, many Muslim voters backed Sen. Bernie Sanders (Vt.). Clinton was too hawkish for them — and may still be even if she earns their votes.

And then there are voters such as Oz Sultan, a counterterrorism analyst and commentator in New York who calls himself “a lifelong conservative.”

“I don’t think Hillary Clinton has the ability to keep our country safe,” he said Wednesday from his home in Harlem, after watching Trump speak at a national security forum. Sultan’s biggest concern is the Islamic State, and Clinton “has gone on a destabilizing spree,” he said, noting the Obama administration’s military offensive in Libya.

Registered Muslim American voters are a starkly diverse and growing constituency, and Mitha, 34, who was named Clinton’s Muslim outreach director last month, is trying to woo them all.

Back in this Gulf Coast city where he grew up, he expected a tough crowd. He already had held roundtable discussions in Michigan, Ohio and Virginia, and he knew that some Muslims in his hometown viewed Clinton as too right-wing or centrist on issues of domestic spying and Middle East policy.

His counter: “I don’t think a presidential campaign has ever hired anyone to do Muslim outreach,” Mitha told his friends. The campaign has looked at the numbers and embarked on an unprecedented outreach to a voting bloc that has the potential to decide elections in several swing states, where support for Clinton has been ticking downward since the Democratic National Convention.

Take Florida, where Clinton remains locked in a tight race with Trump. In a state where the 2000 presidential election was decided by a 537-vote margin for George W. Bush, there are about 180,000 registered voters who are Muslim, Arab and South Asian, the civic nonprofit Emerge USA estimates.

Two years ago, Muslims made up just under 1 percent of the U.S. population, according to the Pew Research Center’s 2014 Religious Landscape Study. But the population is growing; Emerge USA, which collects data on Muslim voters and has a political action committee to support candidates, puts the number at closer to 2 percent of the population.

Florida, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Virginia “alone add up to almost 1 million Muslim voters,” said Khurrum Wahid, a Miami-based lawyer and the organization’s founder. “With a decent voter turnout in those states, Muslims will be the swing vote in both the presidential and many close House races.”

Most Muslim Americans now lean Democratic, according to the Pew study. In past decades, many were fiscally conservative, pro-family and eager to see their cities get tough on crime. Surveys conducted by the Council on American-Islamic Relations (CAIR) and the American Muslim Alliance in the aftermath of Bush’s 2000 election found that between 72 percent and 80 percent of Muslims polled said that they had voted for him. But after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and Bush’s rhetoric on religion and decision to invade Iraq and Afghanistan, the majority began voting Democratic.

At the same time, Muslims are generally less politically active than the larger American population; only 62 percent of those who were U.S. citizens were certain that they were registered to vote, compared with 74 percent of adult U.S. citizens overall, according to Pew.

To reach those voters, the Clinton campaign has appointed two state-level Muslim outreach coordinators to work with Mitha, and the campaign also has dispatched Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minn.), the first Muslim elected to Congress, and Huma Abedin, Clinton’s close adviser and deputy campaign manager, to key swing states across the country.

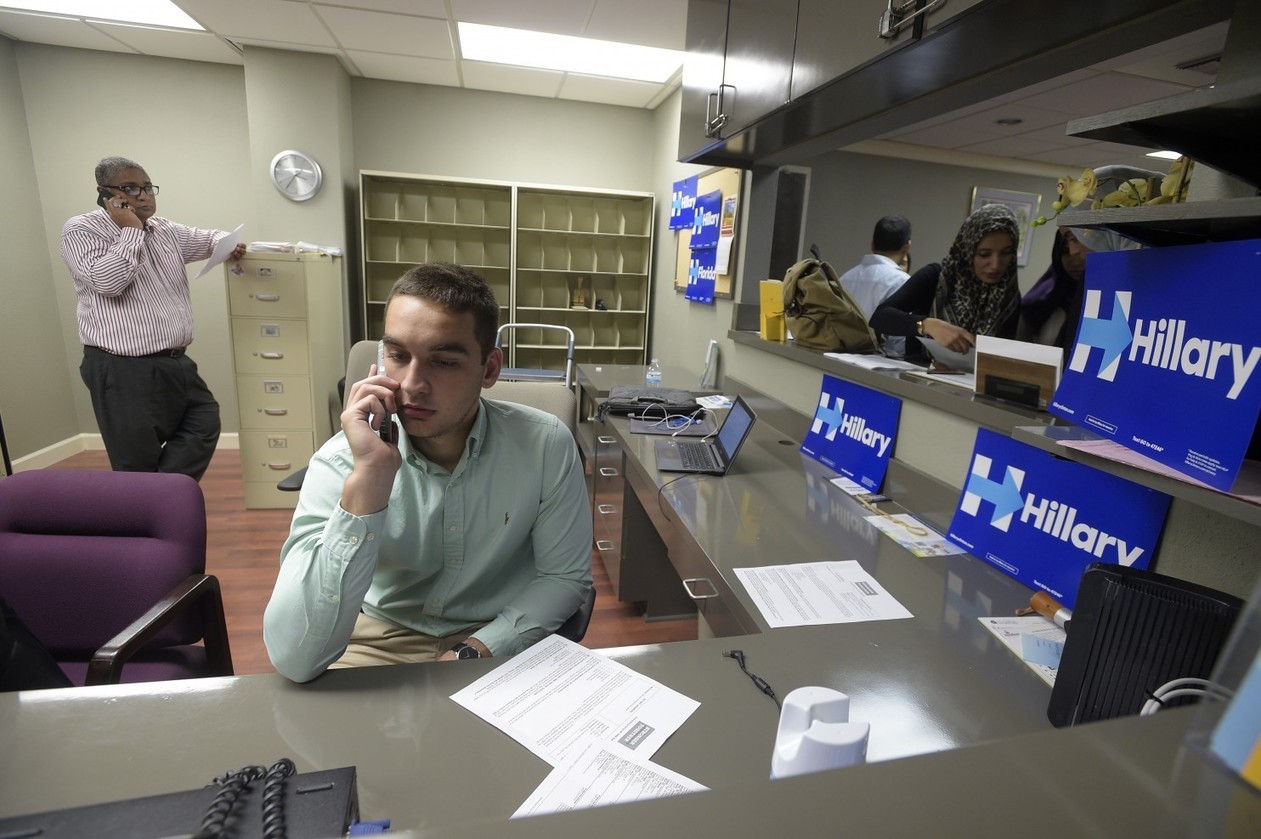

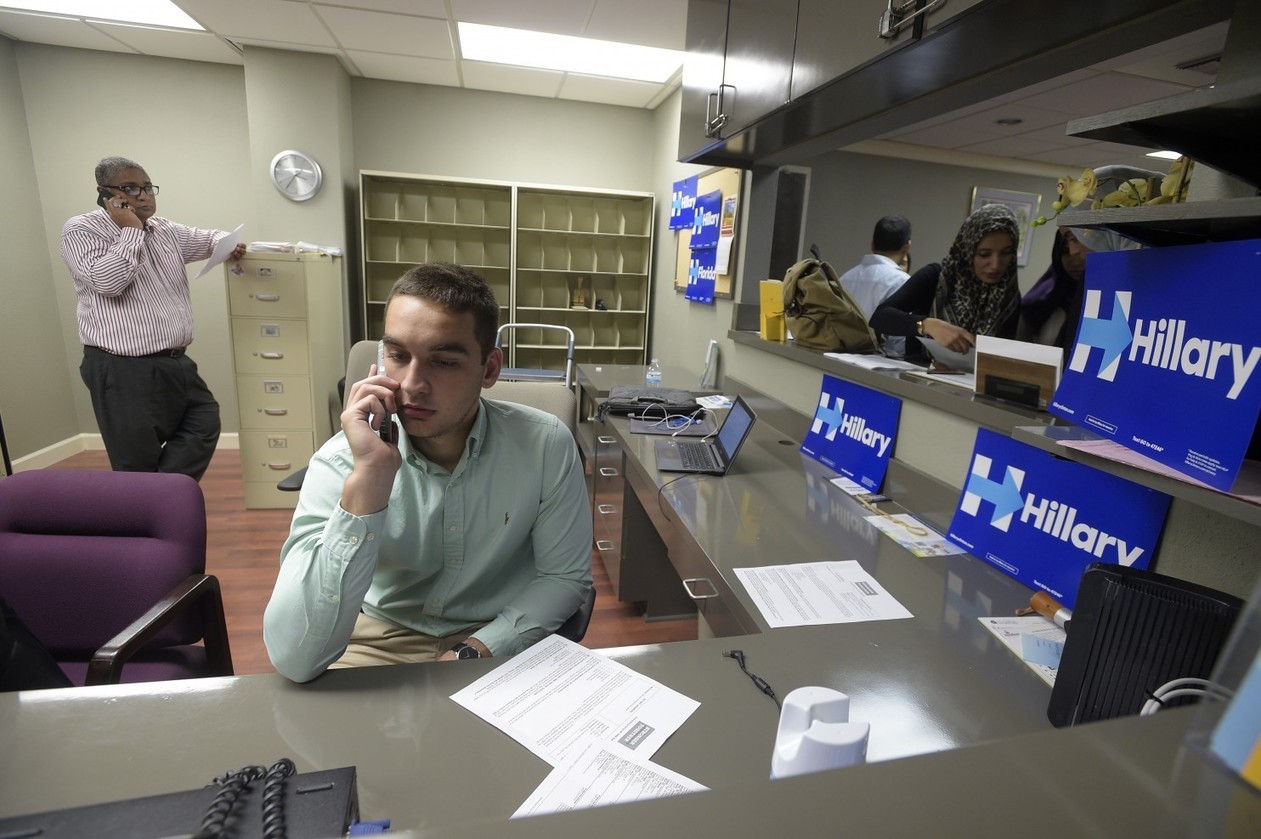

Ellison estimates that he has met with at least 10 Muslim groups since the July convention. One recent Monday morning, he showed up in a tiny Orlando doctor’s office where the campaign was holding its kickoff phone bank for Muslim volunteers and rattled off reasons Muslims should vote for Clinton.

She has fought for children’s rights, he said. She stood up for Abedin when the Trump campaign attacked her. And she has gone out of her way to meet with Muslims, Ellison said, stopping in his home district of Minneapolis to meet with Somali American community leaders.

“The Clinton campaign is more inclusive of the Muslim community than any presidential campaign that I’ve ever seen,” he told the group of phone bank volunteers that included doctors, lawyers, college students, Palestinian Americans, Guyanese Americans, Kenyan Americans and others.

The sheer diversity

One of Clinton’s challenges is the population’s sheer diversity. Nearly a third of all Muslim Americans are black, according to Pew, some of them with deep roots in the distinctly American sect the Nation of Islam. Others — about eight in 10 — are immigrants or the children of immigrants. Muslim Americans come from different ethnic, linguistic and cultural backgrounds; span the economic spectrum; and have policy opinions and priorities that can be just as divergent, community leaders say.

Some, like Sultan, are even likely to vote for Trump, who has called for a ban on Muslim immigrants and surveillance of mosques.

“I know, personally, three doctors” who are voting for him, Azhar Subedar, an Islamic scholar, told Mitha in Tampa.

The Trump campaign did not respond to questions about whether it is also trying to attract Muslim voters or considers the constituency a potential tipping point in any swing states.

This cycle, get-out-the-vote efforts are surging in Muslim communities. The Clinton campaign, Emerge USA, the Washington-based Arab American Institute, CAIR and a range of smaller, local organizations, including mosques, have held voter registration drives, candidate forums and phone banks.

The most common arguments for Clinton offered by her Muslim advocates tend to revolve around Trump.

“Obviously, this election has a sense of urgency that we haven’t felt before,” said Muna Jondy, a Syrian American activist and lawyer from Flint, Mich. “Because it’s not just an option between a Republican and a Democrat. It’s between a fascist and another person.”

“Never before in the history of America has a major party had someone who was screaming bigotry into a megaphone,” Ellison told the phone bank volunteers in Orlando. “No Muslim can sit around and let this happen.”

The Trump factor “doesn’t work with everyone,” said James Zogby, the president of the Arab American Institute, who served as a campaign adviser to Sanders.

Support for Sanders among Muslim voters was “huge,” said Ellison, who also backed Sanders. A Muslims for Bernie 2016 Facebook page, with 7,465 likes, still exists. A Muslims for Hillary 2016 Facebook group has 820 members. Muslims for Trump has 428.

Sanders’s supporters say that, unlike Clinton, the senator from Vermont spoke out about key Muslim voter concerns, such as the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territory.

“It was an issue that always existed in our community,” said Nuren Haider, 31, who is running for Orange County commissioner in Florida. “But he brought it to the limelight,” said Mohammad Shair, a 23-year-old Florida law student who now plans to vote for Green Party candidate Jill Stein.

Ellison tries to remind the disenfranchised Muslims who supported Sanders that Clinton has done a lot of good. He tells them that she regrets her vote in favor of the Iraq War — and that there are congressional votes he regrets, too.

“I also tell them: ‘There’s going to be a president, and it’s not going to be one of these third-party candidates. It’s going to be the Democrat or the Republican. . . . So understand the clear and present danger presented by the alternative,’ ” he said.

That binary choice makes some Muslim voters “feel like they have no choice,” Amina Spahic, the Tampa Bay regional director for Emerge, told Mitha and the others who gathered at the mosque in Tampa.

Mubarak, the Tampa lawyer, said he regretted his votes for President Obama and what he considers the administration’s hawkish drone policy and increased federal surveillance of Muslims. He wants to believe that Clinton would be different. But “the problem is we’ve been burned before so many times,” he said, “and frankly we’re tired of it.”

To those voters, Clinton’s statements on the issues provide little reassurance.

The campaign website’s explanation of her stance on combating terrorism starts with the words “radical jihadists” — a term that some Muslim activists say stigmatizes Islam. Her national security page makes prominent reference to “protecting Israel” but no similar reference to Palestinians and Syrians, which some voters say they’d like to see. In a March speech to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, a lobbying group that aligns with the Israeli right and is opposed by many liberal American Jews, she twice referred to “Palestinian terrorists.”

Ghazala Salam, a Clinton delegate at the Democratic National Convention in July who chairs the American Muslim Democratic Caucus in Florida, said the former secretary of state is simply the most qualified to do the job. Whether you like all of her policies or not, Salam said, she knows how to deal with the outside world.

Skeptical Muslim voters are “coming around,” she said, and what they do next will be critical to the future of Muslim participation in U.S. politics.

Had Muslims been more politically engaged before the 2016 campaign, “we would have not really heard a person like Trump come out and say openly the things he did about Muslims,” Salam said. “For it not to happen again, we have to have proactive engagement in every level of government.”

Source: www.washingtonpost.com