Ancient Egyptian works to be published together in English for first time

Dalya Alberge

The Guardian

Ancient Egyptian texts written on rock faces and papyri are being brought together for the general reader for the first time after a Cambridge academic translated the hieroglyphic writings into modern English.

Until now few people beyond specialists have been able to read the texts, many of them inaccessible within tombs. While ancient Greek and Roman texts are widely accessible in modern editions, those from ancient Egypt have been largely overlooked, and the civilisation is most famous for its monuments.

The Great Pyramid and sphinx at Giza, the tombs in the Valley of the Kings and the rock-cut temples of Abu Simbel have shaped our image of the monumental pharaonic culture and its mysterious god-kings.

Carved text from pyramid. Photograph: Dalya Alberge

Toby Wilkinson said he had decided to begin work on the anthology because there was a missing dimension in how ancient Egypt was viewed: “The life of the mind, as expressed in the written word.”

The written tradition lasted nearly 3,500 years and writing is found on almost every tomb and temple wall. Yet there had been a temptation to see it as “mere decoration”, he said, with museums often displaying papyri as artefacts rather than texts.

The public were missing out on a rich literary tradition, Wilkinson said. “What will surprise people are the insights behind the well-known facade of ancient Egypt, behind the image that everyone has of the pharaohs, Tutankhamun’s mask and the pyramids.”

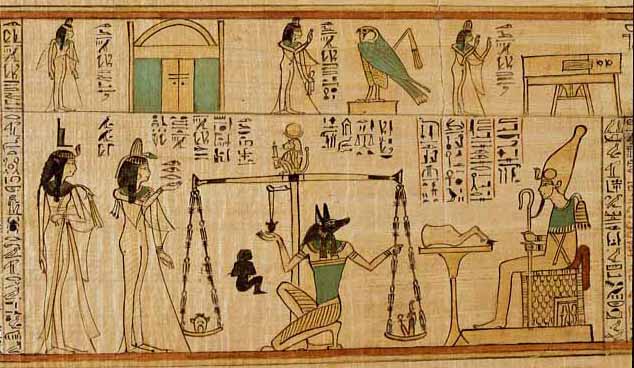

Hieroglyphs were pictures but they conveyed concepts in as sophisticated a manner as Greek or Latin script, he said. Filled with metaphor and symbolism, they reveal life through the eyes of the ancient Egyptians. Tales of shipwreck and wonder, first-hand descriptions of battles and natural disasters, songs and satires make up the anthology, titled Writings from Ancient Egypt.

Penguin Classics, which is releasing the book on Wednesday, described it as a groundbreaking publication because “these writings have never before been published together in an accessible collection”.

Wilkinson, a fellow of Clare College and author of other books on ancient Egypt, said some of the texts had not been translated for the best part of 100 years. “The English in which they are rendered – assuming they are in English – is very old-fashioned and impenetrable, and actually makes ancient Egypt seem an even more remote society,” he said.

In translating them, he said, he was struck by human emotions to which people could relate today.

The literary fiction includes The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor, a story of triumph over adversity that Wilkinson describes as “a miniature masterpiece”. It is about a magical island ruled by a giant snake – his body “fashioned in gold, his eyebrows in real lapis lazuli” – who shares his own tragedy in encouraging a shipwrecked sailor to face his predicament.

“I was here with my brothers and my children … we totalled 75 snakes … Then a star fell and they were consumed in flames … If you are brave and your heart is strong, you will embrace your children, you will kiss your wife and you will see your house,” it reads.

Letters written by a farmer called Heqanakht date from 1930BC but reflect modern concerns, from land management to grain quality. He writes to his steward: “Be extra dutiful in cultivating. Watch out that my barley-seed is guarded.”

Turning to domestic matters, he sends greetings to his son Sneferu, his “pride and joy, a thousand times, a million times”, and urges the steward to stop the housemaid bullying his wife: “You are the one who lets her do bad things to my wife … Enough of it!”

Other texts include the Tempest Stela. While official inscriptions generally portray an ideal view of society, this records a cataclysmic thunderstorm: “It was dark in the west and the sky was filled with storm clouds without [end and thunder] more than the noise of a crowd … The irrigated land had been deluged, the buildings cast down, the chapels destroyed … total destruction.”

The number of people who can read hieroglyphs is small and the language is particularly rich and subtle, often in ways that cannot be easily expressed in English.

Wilkinson writes: “Take, for example, the words ‘aa’ and ‘wer’, both conventionally translated as ‘great’. The Egyptians seem to have understood a distinction – hence a god is often described as ‘aa’ but seldom as ‘wer’ – but it is beyond our grasp.”

Words of wisdom in a text called The Teaching of Ani remain as true today as in the 16th century BC: “Man perishes; his corpse turns to dust; all his relatives pass away. But writings make him remembered in the mouth of the reader.”

Source: www.theguardian.com