Are Japanese and Arabs More Alike Than We Think?

By: Arwa Almasaari / Arab America Contributing Writer

The Arab world encompasses twenty-two nations, spanning from West Asia to North Africa. Japan, on the other hand, is an island nation composed of over two hundred inhabited islands in the Far East. Despite their vast geographical distances, linguistic differences, and distinct ethnic identities, Japanese and Arabs have a lot in common. For instance, Arabs call attentive care for guests “thiafah,” while the Japanese call it “omotenashi,” with both terms reflecting a cultural value for hospitality. Arwa Almasaari, Arab America contributing writer, highlights the common cultural practices that celebrate our shared values in an increasingly diverse world.

Table Manners

When it comes to dining, both Arab and Japanese cultures emphasize respect and politeness at the table. They begin and end meals with expressions of gratitude. Arabs say “bismillah” (In the name of God) before eating, while the Japanese say “itadakimasu” (I humbly receive), to express their appreciation for the food. After the meal, Arabs express their thanks with “Alhamdulillah” (Praise be to God), whereas the Japanese say “Gochisousama” (It was a feast), honoring the effort that went into the meal preparation.

Both cultures discourage disruptive table manners such as blowing your nose, burping or talking with your mouth full. However, a notable difference is found in the custom of slurping noodles. In Japan, it is considered a sign of enjoyment, while in most Arab communities, it is deemed impolite.

Drinking soup directly from the bowl is acceptable in Japan, but in Arab cultures, this practice is generally seen as improper in formal settings. It may be more acceptable in casual situations. In both cultures, spoons are typically used to consume solid ingredients in soup.

Hospitality

Hospitality is a cornerstone of both Arab and Japanese societies. Hosts go above and beyond to anticipate the needs of their guests. This thoughtful care is referred to as “omotenashi” in Japan and “thiafah” in Arab cultures. In both traditions, it is customary for the host to greet guests at the door and walk them out when they leave as a sign of respect. Japanese hosts often invite guests in with “Dōzo o-hairi kudasai,” while Arabs might use phrases like “Ahlan wa Sahlan” or “Hayiakum Allah.”

It’s also common for hosts to take care of guests’ belongings, such as coats or hats, and return them at the end of the visit. In both cultures, shoes are typically removed at the entrance. This is especially important when stepping on tatami mats in Japan or rugs in Arab households. However, this practice is gradually becoming less common in some Arab communities.

Expressing gratitude is central to both cultures. After a meal, it is customary to praise the food and thank the host. When offering something to a guest, Japanese hosts say “dōzo,” while Arabs use tafaddal (for males), tafaddali (for females), or tafaddalu (for plural guests).

Guests also play a role in hospitality by bringing gifts. In Japan, these gifts can vary widely, while Arabs often bring food items. Both cultures have a tradition of seating the most important guests in the place of honor, farthest from the entrance. In Japan, the host typically occupies the least important seat as a gesture of humbleness. With the exception of the host being an elder or a prominent figure, hosts in Arab communities often opt for the least important seat. This gesture indicates their readiness to serve their guests.

In formal settings, Japanese hosts refill drinks like sake, checking and replenishing each other’s cups. Similarly, Arab hosts refill small coffee or tea cups throughout the visit. In Japan, leaving a little liquid in the cup indicates that you don’t want more. Similarly, Arabs may use gestures like covering the cup with their hand to politely decline additional servings.

General Social Etiquette

In Japan, tipping is generally not practiced because it is believed that the price of a service reflects its quality. In the Gulf region, tipping is also considered optional and is typically reserved for exceptional service. However, the Arab world is diverse, and tipping practices can vary significantly from one country to another. In contrast to Japan and the Gulf region, countries like Egypt and Morocco have more established tipping customs, where gratuities are more commonly given.

Names and titles also reveal important cultural similarities. Japanese people typically avoid using first names, opting instead for honorific suffixes like “-san” attached to the last name. Similarly, in Arab culture, individuals are often addressed by their titles or with terms like “Abu” (father of) or “Um” (mother of), followed by the name of their eldest child. These practices underscore the importance of respect in both societies.

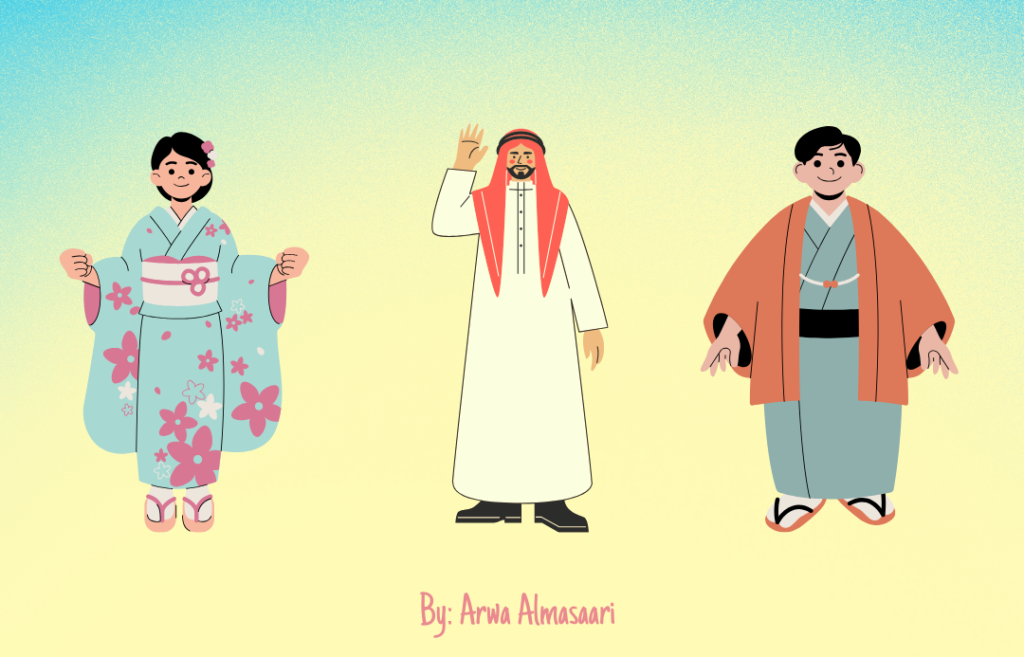

Modesty

Modesty is a valued trait in both Japan and the Arab world, though specific standards can vary across regions. In Japan, women are generally expected to cover their cleavage, shoulders, and sometimes upper arms. Similarly, modesty norms in the Arab world differ between countries and urban or rural areas, but they largely align with those of Japan. This emphasis on modesty is reflected in traditional clothing. Japanese men wear the kimono, while Arab men wear the thobe—both long, loose-fitting garments that extend to the ankles. While the women’s kimono is typically more form-fitting at the waist compared to traditional Arab women’s attire, such as the jallabiya or kaftan, both styles maintain long sleeves and ankle-length hemlines. Both kimonos and jallabiyas feature intricate embroidery that signifies cultural importance and social status in their respective regions.

The Takeaway

Ultimately, examining cultural values reveals that cultures often share more than we realize. Recognizing the parallels between Arab and Japanese traditions enriches our understanding of both cultures and fosters a sense of global community.

Arwa Almasaari is a scholar, writer, and editor with a Ph.D. in English, specializing in Arab American studies. She often writes about inspirational figures, children’s literature, and celebrating diversity. You can contact her at arwa_phd@outlook.com

Check out our blog here!