Arabic Influences in the English Language

By: Habeeb Salloum/Arab America Contributing Writer

Visitors from Britain or North America strolling through an Arab city and listening to the Arabic conversations of passersbys are usually unaware that the English language includes a good number of words derived from that strange tongue. Yet, if they are not students of linguistics, they cannot be blamed. Many of the Arabic words borrowed by English are so anglicized that, for the layman, it is difficult to identify their true origin.

My late colleague James Peters and I examined over 500,000 English words and found that, from these, there are some 3,000 basic words and 5,000 of their derivatives which have some connection with the language of the Qur’an. Upward to 500 of the basic words are common in the everyday language.

To tell the story of how these Arabic words entered the language of Shakespeare is a fascinating story. At the dawn of Islam in the 7th century, the Arabic language and Islam became inseparable. As the Muslim armies moved through North Africa, then through the Iberian Peninsula, the tongue of the Arabs as a part of the new religion, spread like wildfire. The masses of newly-converted Muslims, in many cases, took as their own the idiom of the conquering desert men. In a few decades, Arabic became the intellectual medium which united the new world of Islam.

Eastward, from the Arabian heartland, the Muslim armies occupied countries which had developed numerous civilizations and cultures. However, unlike a good number of conquerors before and after, they did not destroy but preserved the cultures they had overwhelmed. In the ensuing centuries, they absorbed the learning of these lands to produce an Arab-Islamic civilization that was to be mankind’s beacon for hundreds of years.

From the conquered lands, the Arabs borrowed thousands of scientific and technical words, greatly enriching their poetic tongue. Between the 8th and 12th centuries, this enhanced Arabic, with an endless vocabulary, became the intellectual and scientific language of the entire scholastic world.

The men of letters and scientists in both eastern and western lands had to know Arabic if they wished to produce works of art or science. During these centuries, Arab Andalusia by itself generated more books in Arabic than were produced in all the other languages of Europe. The Arabic libraries in Muslim Spain, some containing over half a million manuscripts, had no match in all the countries of Christendom.

Unlike the remainder of Europe where only the clergy were literate, the majority of people in Muslim Spain learned to read and write in the schools that were to be found in almost every town. European students from the northern Christian lands came to study in these institutions and when they returned, their vocabularies were enriched with many Arabic words and phrases.

At the same time, the Christians in the Iberian Peninsula living under Muslim rule became proficient in Arabic, in many cases preferring it to their own Romance languages. Hence, in both the written and spoken idioms, Arabic words that crept into the linguistic heritage of Spain and the other European languages were later adopted.

As they borrowed from the rich repository of Arabic scientific and technical words, the Christian languages were enhanced and stimulated. Added to this, the movement of Arabic words into the tongues of Europe was accelerated by the translation of Arabic books, mostly in Toledo – captured early in the Reconquista. Hundreds of Arabic words entered the European languages by way of these translations. Historians have asserted that the reproduction of Arabic works from the most advanced civilization in that age transformed European thinking and put the continent on the road to advancement and prosperity.

Besides the Iberian Peninsula, there were two other points from which Arab influences spread to Europe: Sicily, after its conquest and Arabization; and the Middle East by way of the Crusades.

As in Spain, the Sicilians borrowed many words from their conquerors and the ‘men of the cross’ brought back to the Europe of the Dark Ages many new products, ideas and words borrowed from Arabic. The European languages, among them English, were enriched, by the newly acquired vocabulary of these returning warriors, including a good number of Arabic words in all fields of human activity.

It was only natural that the West would borrow words from the Muslim East – the most advanced part of the world in that era. In the same fashion as in our times words from English – the language of industry and science – creep into foreign tongues, so it was with Arabic at the time of the Crusades.

In the ensuing years, on a continuing basis, Arabic words began to flow into English through intermediate languages like French and Portuguese. Later, from the 18th to the 20th century, when Britain expanded its Empire to the four corners of the world, a variety of Arabic words entered English by way of Africa, the Middle East and the Indian sub-continent. Even after colonialism disappeared, the inflow of Arabic words into English has continued until our times.

If one leafs through the modern English dictionaries, words of Arabic origin are to be found under every letter of the alphabet. It will surprise many to know that in a study made of the Skeats Etymological Dictionary it was found that Arabic is the seventh on the list of languages that has contributed to the enrichment of English. Only Greek, Latin, French, German, Scandinavian and the Celtic group of languages have contributed more than Arabic to the tongue of Shakespeare.

These Arabic loan words indicate that the Arabs contributed to almost all areas of western life. In architecture; food and drink; geography and navigation; home and daily life; music and song; personal adornment; cultivation of plants; the sciences; the domain of the heavens; sports; trade and commerce; the theatre of the macabre; the abode of animals and birds; the clothing and fabric trade; and in the fields of chemicals, colour and minerals, one finds Arabic words and Arab transmitted words from other languages into the European languages.

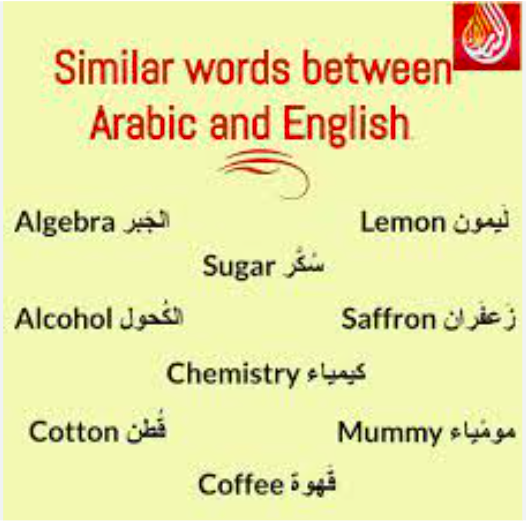

One can see the immense Arab contribution to English if we examine only one of these areas – food and drink. Alcohol is derived from the Arabic al-kuhl; apricot – al-barquq; artichoke – al-khurshuf; arrack – ‘araq; banana – banan; candy qand; cane – qanah; caramel – qanah; caraway – karawya; carob – kharrub; coffee and cafe – qahwah; cumin – kammun; jasmine – yasmin; julep – julab; kabab or kabob – kabab; lemon, lemonade and lime – laymun; mocha – mukha (port city in Yemen); orange – naranj; saffron – za’faran; salep – tha’lab; sesame – simsim; sherbet – sharbah; sherry – Sherish (the Arab name of the city of Jerez de la Frontera in Andalusia); spinach – isbanakh; sugar – sukkar; sumach – summaq; syrup – sharab; tamarind – tamr hindi; tangerine – Tanjah (Arab name for Tangiers, Morocco); tarragon – tarkhun; tumeric – kurkum; and tuna – tun are a number of these words which have become as English as Yorkshire pudding.

Even in our times, the Arabic contribution has not stopped. As in most other fields, in the domain of food and drink the flow of Arabic words into English continues. During the 20th century the words: burghul or bulgar, from the Arabic burghul; couscous – kuskus; falafel – filafil; halvah – halawa; hummus – hummu; kibbe or kibbeh – kubbah; leban – laban; shish kebab – shish kabab; and taboula – tabbulah are now to be found in most dictionaries as English words.

This sample of Arabic words in only one area of the English language makes it clear that the language of the Qur’an has contributed and is continuing to give enrichment to today’s most widespread tongue on the globe. In today’s world, Arabic is the only language in which an ordinary Arabic speaking person can pick up a 1,500-year-old Arabic book and understands its contents. All European languages, including English, did not exist at that time. The older languages such as Greek, Persian and Chinese are, in our time, much different and the older versions of these tongues, and only understood by scholars.

With such a venerable history, there is no doubt that Arabic, which the Arabs and, in fact all Muslims, consider to be ‘the language of paradise’, will continue its worldly role.