Arab Spring is Over, Done! An Anatomy of Hope—Dashed by the Realities of Raw National Power Against the People

By: John Mason / Arab America Contributing Writer

Early film clips of pro-democracy protests in the Middle East and North Africa beginning in 2010 and 2011 gave some hope to Arabs for a different life. Tunisia and Egypt gave the most, initial hope when authoritarian regimes were toppled by the ‘street.’ The struggle was shared by Arabs across the region, who just wanted to eliminate corruption and obtain a better quality of life. With the recent arrest of Tunisia’s most prominent opposition leader, Rached Ghannouchi, the Arab World may have lost its last best hope.

Arab Spring’s pro-democratic protests against autocratic regimes—beginning of the end

When we saw early film clips of protests in the Middle East and North Africa beginning in 2010 and 2011, we might have thought, it impossible. We stayed glued to our cable screens, in the vague hope that, yes, maybe it is possible. ‘It’ was the wave of pro-democracy protests and uprisings occurring over the MENA region.

Tunisia and Egypt gave the most, initial hope. There, authoritarian regimes were actually toppled by the ‘street.’ While these protests seemed to be causally linked, as if part of a vast conspiracy, they were inspired by the effect of citizens’ grievances over their leaders’ political and economic repression. They were mostly met with ferocious crackdowns by national security forces.

Tunisia’s so-called ‘Jasmine Revolution’ in December 2010 was the first demonstration, according to Britannica, “catalyzed by the self-immolation of Mohammed Bouazizi, a 26-year-old street vendor protesting his treatment by local officials.” A street protest began in a central Tunisian town and the government used violence to try to squelch it. The Tunisia government also offered some political and economic concessions, to no avail.

The ’street’ prevailed, however, leading President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali to step down and flee. Over the next several years, Tunisians held a free election to draft a new constitution and democratically elect a president and prime minister. This process put Tunisia on the MENA map as “the first country of the Arab Spring protests to undergo a peaceful transfer of power from one democratically elected government to another.” We will check back on Tunisia later in the report to see how this all worked out.

The next moment of inspiration in the Arab Spring was Egypt’s January 25, 2011 revolution. Egypt had never had a rural, peasant revolution but this one, urban in character, organized by young Egyptians in Cairo and other urban centers across the country through social media, spread fast and furiously. Britannica reported, “After several days of massive demonstrations and clashes between protesters and security forces in Cairo and around the country, a turning point came at the end of the month when the Egyptian army announced that it would refuse to use force against protesters calling for the removal of President Hosni Mubarak.” Mubarak took the hint, resigned, and gave power to a council of senior military officers.

Yemen, Bahrain, Libya, and Syria may have taken their inspiration to revolt from Tunisia and Egypt. In these cases, however, the protests resulted in bloody struggles, some lasting for years. These struggles involved opposition groups fighting one another, in civil war, or against ruling regimes. We will not focus on these four countries experiences, except to mention that internal strife still affects them. And we shouldn’t leave out Algeria, Jordan, Morocco, and Oman, where leaders gave concessions to nascent pro-democracy protesters to cut off any widespread protest movements.

Perhaps ‘Arab Spring’ was the wrong label all along. As the annual season of regeneration and hope, spring is the natural culmination of the preceding seasons. But in the case of many, not all, Arab countries, they have been enduring winter for more centuries than they care to tell. Perhaps we’re being too literal about the seeming possibilities of Arab citizens taking over their own lives. For too long, the justification that ‘He who rules does so at the will of Allah!’ is a rationalization we should dispense with. Especially since there is no way on Earth to prove it.

The pro-democracy protest movements in the Arab World all represented a struggle shared by Arabs across the region who just wanted to try to eliminate corruption and give citizens a better quality of life. These protests have not completely ended, just because the Arab Spring really didn’t succeed. As we’ve seen, in many Arab countries, some of which are close to failed states, governments are incapable of managing major continuing crises. Whether something akin to another Arab Spring emerges is unknown, but if it did, it is unclear if it would have a better chance of success than the first one.

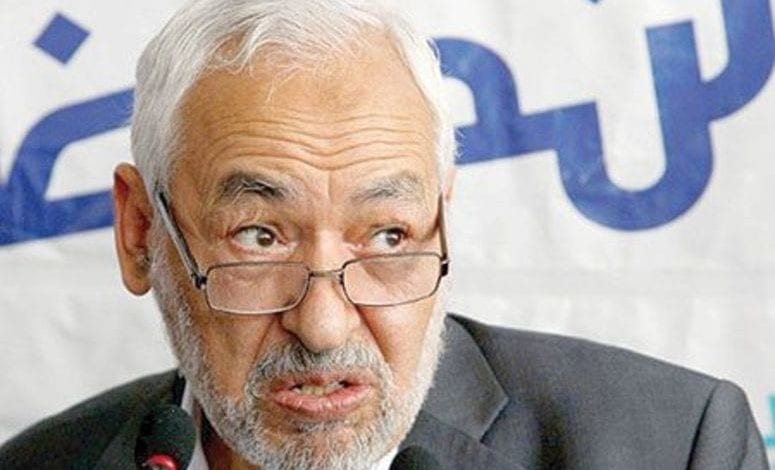

Tunisia—Nail in the coffin: the birthplace of the Arab Spring is now its graveyard

With the recent arrest of Tunisia’s most prominent opposition leader, Rached Ghannouchi, the Arab World may have lost its last best hope. According to The New Yorker Magazine, “This week, the police finally came for Rached Ghannouchi, the leader of Tunisia’s largest political party and the Arab world’s most influential thinker about the potential synthesis of liberal democracy and Islamic governance.” This act puts Tunisia on the map as the birthplace of the Arab Spring, the last place where it failed, and now the graveyard for this once aspirational idea.

Tunisia worked moderately well as a relatively free country, a democracy if you will, for about a decade. President Kais Saied then came along, seeing an opening to intrude himself, closed the parliament, and became a one-man show. The country’s constitution is authoritarian, as is Saied, as he puts his critics in jail. Ghannouchi is one of them. Ghannouchi is himself a study in the complexities and nuances of Arab political culture and Islam.

Ghannouchi, born in 1941, grew up poor in southern Tunisia, a region often neglected by national authorities. He traveled and worked outside the country for several years, returning to Tunis in 1971. This was a period when the Muslim Brotherhood was gaining momentum in the face of autocratic forms of government. In and out of jail over decades, Ghannouchi could not find refuge in a fellow Arab country and fled to London.

In England, Ghannouchi found a way to marry the idea of Britain’s liberal democracy with an Islamic way of life. He wrote about his idea, averring “A true Islamic state must be founded on ‘freedom of conscience’ for Muslim and non-Muslim alike. Quoting a revered twelfth-century scholar, Ghannouchi urged Islamists to learn from Western democracy—to benefit “from the best of human experiments regardless of their religious origins…”

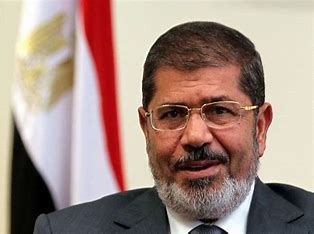

When he returned to Tunisia, in 2011, in the midst of the protests, Ghannouchi was instrumental in making “the country’s political transition the most liberal in the region, and he did his best to salvage the prospects for democracy elsewhere.” He traveled to Egypt to aid Mohamed Morsi, Egypt’s first and now only democratically elected President. Ghannouchi advised Morsi to offer a softer version of the Muslim Brotherhood’s approach to governing, especially regarding Egypt’s large Coptic Christian population. Morsi disagreed and protests against his leadership intensified. Whether he’d have had a chance to reason with the protesters, “We’ll never know on July 3, 2013, General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi—now President Sisi, possibly for life—ousted Morsi from power, ending Egypt’s thirty-month experiment with democracy and freedom.”

Back in Tunisia, Ghannouchi found an important niche for his Islamist party, called Ennahdha, meaning ‘the renaissance.’ He also decided to become a politician, running for and winning the speakership of the parliament. The new president, Saied, follows an Islamic platform: the state “will work to achieve the objectives of pure Islam.” He has reared the ugly head of gays as deviants and sub-Saharan African immigrants fulfilling the ‘replacement theory’—sound familiar?

Ghannouchi is clearly too much of a threat to Saied. Hence, the President put Ghannouchi under arrest. The New Yorker suggests that “the imprisonment of a leader as singular as Ghannouchi is also a setback to the wider world. For Islamists who espouse violence, his imprisonment is a vindication—new evidence of the futility of the ballot box. And the silencing of his voice is a loss to the West, too.”

Without putting too fine a point on it, Tunisia is now back in the column of autocracy opposite the column of liberalism and democratic governance. More important, however, is the loss of the chance to marry Islam to liberal democratic principles. Ghannouchi is not convinced, even while he is detained, saying “Trust in the principles of your revolution, and that democracy is not a passing thing in Tunis.” We shall see.

Sources:

–“Arab Spring: pro-democracy protests,” Britannica, 4/6/2023 (last update)

–“Tunisia Arrests Its Most Prominent Opposition Leader: Rached Ghannouchi has been a voice for democracy in his nation and across the Muslim world,” New Yorker Magazine, 4/23/2023.

John Mason, PhD., who focuses on Arab culture, society, and history, is the author of LEFT-HANDED IN AN ISLAMIC WORLD: An Anthropologist’s Journey into the Middle East, New Academia Publishing, 2017. He has taught at the University of Libya, Benghazi, Rennselaer Polytechnic Institute in New York, and the American University in Cairo; John served with the United Nations in Tripoli, Libya, and consulted extensively on socioeconomic and political development for USAID and the World Bank in 65 countries.

Check out our Blog here!