An Architect’s Plea for a Lebanese Historic Recognition System

By: Ralph I. Hage / Arab America Contributing Writer

Arab America contributing writer, Ralph Hage, calls for the creation of a Lebanese Historic Recognition System to preserve Lebanon’s rich architectural heritage. Through his personal experience restoring the Daoud Corm house, Hage highlights the urgent need for a legal framework to protect Lebanon’s built heritage. By drawing comparisons with successful international models, Hage outlines how Lebanon can establish its own tailored system to safeguard its invaluable landmarks for future generations.

“Where’s the head?”

“Maybe on a shelf somewhere in one of these apartments nearby.” I leaned in a little closer. The only remnant of the bust was a stone base that read “Daoud Corm.”

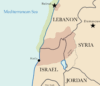

It was early spring of 2020, and I had surveyed and drawn maps of an ancient house in Bsous, Lebanon—a mountain town overlooking the Mediterranean, historically renowned for its apricots. The house was one of the few remaining traditional structures in an area increasingly dominated by the rise of apartment buildings.

The house had belonged to the renowned Lebanese painter Daoud Corm, often regarded as the father of Lebanese painting. He was a teacher and mentor to the young Khalil Gibran, author of The Prophet, as well as to artists Khalil Saleeby and Habib Srour.

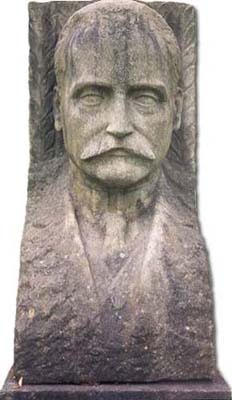

The bust was created by Youssef Howayek, a Lebanese painter, sculptor, and writer. Howayek befriended Khalil Gibran in France, where they both studied under Auguste Rodin—widely regarded as the founder of modern sculpture—between 1909 and 1910. Later, Howayek went on to design the first sculpture for Martyrs’ Square in downtown Beirut.

A two-story traditional Lebanese residence, built at the turn of the 20th century with mid-century concrete additions by architect Bahij Makdisi, was being documented by its owner. The goal was to clear the debris that had accumulated around it over the past century, add a red tile roof, and secure the openings to prevent theft. However, during the 1975–1990 Lebanese Civil War, the house was stripped down to its bare skin and bones.

Assessing the Structural Integrity of the Daoud Corm House

The first step was to assess the structural integrity of the house. To consult an expert, I reached out to Dr. Amer El Souri, a structural engineer and friend who had taught me at the American University of Beirut.

Dr. El Souri explained that there were essentially two schools of thought on the matter. The first assumed that the house had already fully settled structurally over its century-long history, a theory that could be confirmed through structural analysis. The second approach was more skeptical, presuming the house might not be structurally sound and requiring a more thorough investigation. This typically involves examining cracks in the walls, which can indicate the structure’s health, checking for changes in interior and exterior floor levels, and determining whether interventions like foundation repairs are necessary.

A Case for Historic Preservation

“This house should be a museum,” I thought to myself.

In terms of American painters, Corm’s stature is comparable to that of Benjamin West. Both studied in Italy and supported the careers of numerous artists who later achieved great success in their respective countries. West’s birthplace was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1965 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. It is now part of the Swarthmore College campus in Swarthmore, Delaware County, Pennsylvania.

Even if it were not to be transformed into a museum, the house possesses several features that make it an ideal candidate for adaptive reuse as a residence. These include historic preservation, sustainability, lower construction costs, and energy efficiency, to name just a few.

Some countries have creatively addressed this issue by offering renovators financial or tax incentives. For example, certain municipalities in Italy and Spain charge just one Euro for a dilapidated house, with the condition that the buyer renovates it within a fixed period. In the United States, the National Historic Landmark and National Register of Historic Places systems provide legal protection, historic building fee waivers, specific building codes, site plan reviews, and tax relief. The United Kingdom uses the blue plaque system, linking historical figures to present-day buildings and raising awareness of their significance. However, it does not provide legal protection for the property. Despite being one of the most historically significant countries in the world, Lebanon lacks such programs.

Legal Implications for the Protection of Built Heritage in Lebanon

Although Lebanon lacks overarching programs or legal frameworks specifically designed to protect built heritage, buildings deemed historic are currently governed by the Ancient Antiquities Law, which was originally issued in 1933 by Decree 166 and has not been revised since the French Mandate period (Dispensaire Juridique, 2021; AUB University Libraries, Library Guides). Article 1 of this law seeks to protect structures built before 1700 AD. Culturally significant buildings constructed after 1700 AD may also be considered “antiquities” and subject to this law if their preservation is deemed to serve the public interest from both artistic and historical perspectives and if they are recorded in the Historical Buildings General Inventory Registry List (Haroun and Abdul Massih, 2013).

According to Article 21 of the law, the list includes stationary examples of historical, artistic, and public significance that may be owned by the state, individuals, localities, religious sects, or companies. Currently, adding buildings or places of historical significance to this list is at the discretion of the Lebanese Director General of Antiquities (Bou Aoun, 2020), and this remains the primary mechanism preventing their demolition.

The Ancient Antiquities Law outlines two steps for protecting historically significant buildings or places. The first step involves adding the site to the list, while the second requires official registration as historically significant, issued through a verdict from the Council of Ministers (Dispensaire Juridique, 2021). In 2017, a draft law (Decree Number 1936) was proposed to the Lebanese parliament regarding the protection of these historical sites, but it has yet to be passed.

Lebanon has ratified the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, as outlined in Law No. 19/1990. According to Article 4 of this law, the Lebanese government is obligated to ensure the identification, safeguarding, preservation, maintenance, and transmission of its cultural and natural heritage for future generations.

Article 5 of this law addresses its implementation. The Lebanese government is required to integrate the protection of its cultural and natural heritage into comprehensive planning programs. It must establish services for its protection and maintenance, conduct research to reverse any damage and adopt necessary measures to identify, protect, conserve, maintain, and rehabilitate these heritage sites.

Limitations of the Current Legal State of Affairs

The Ancient Antiquities Law has several flaws and ambiguities that undermine the effective protection of historic buildings and sites. One major issue is the lack of clear criteria for defining what qualifies as a historical example. This has led to numerous instances where property owners submit petitions to have their properties removed from the classification and registry list (Bou Aoun, 2020), enabling them to demolish these buildings and construct new ones for capital gains.

In addition to the Daoud Corm house, many other landmarks and sites in Lebanon lack proper recognition and protection. These range from biblical sites like the Sour Hippodrome and Baalbek to more modern landmarks, such as Martyrs’ Square, Horsh Beirut, the Hotel Palmyra in Baalbek—where the Declaration of Greater Lebanon was signed—and a dilapidated house in Zuqaq El Blat, where Fairuz, one of the most iconic singers in Arab history, spent her childhood.

Heritage Purgatory

Despite numerous national crises and considerable efforts, the Daoud Corm house was never renovated, and the missing bust was never recovered. However, Corm’s grandchildren own a bust, also created by Howayek, which they believe closely resembles the stolen one.

A sculpture of Daoud Corm created by Youssef Howayek (from the collection of Charles Corm’s family).

The Urgency of Creating a Lebanese Historic Recognition System

Creating and implementing a legal framework to ensure the sustainability of Lebanon’s built heritage is essential, as it plays a vital role in preserving the country’s shared identity and collective memory. This initiative should be carried out independently at the national level, without overly relying on external organizations such as UN-Habitat Lebanon, the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, or UNESCO. It is important to note that relying on the Ancient Antiquities Law, originally issued in 1933 by Decree 166, is insufficient. This law is vague, incomplete, and limited in scope, failing to provide a comprehensive legal framework for protecting Lebanon’s built heritage. By learning from successful models in other countries, Lebanon can develop its own tailored framework. Establishing systems like a Lebanese National Historic Landmark designation and a National Register of Historic Places could be a valuable starting point.

References

- Massih, Jeanine Abdul. “An Assessment of the Lebanese Heritage Law from the Twentieth to the Twenty-First Century.” Protecting the Cultural and Archaeological Heritage of the Mediterranean Region Legal Issues, 1 Jan. 2013

- Beirut’s Heritage Buildings. University Libraries: Library Guides. American University of Beirut.

- Bou Aoun, Cynthia. 2020. Heritage Buildings After the Beirut Explosion: Initiatives so that Solidere 2 is Not Repeated.سينتيا بوعون. 2020. الأبنية التراثيّة بعد انفجار بيروت: مبادرات كي لا تتكرّر سوليدير 2

- Bou Aoun, Cynthia. 2020. Protecting Heritage Buildings while Awaiting Law (2): Draft Law for the Protection of Heritage Buildings. [سينتيا بوعون.2020. حماية الأبنية التراثيّة في انتظار القانون (2): مشروع قانون حماية الأبنية التراثيّة]

Ralph Hage, a Lebanese American architect and writer, divides his time and work between Lebanon and the United States.

Check out our blog here!