Alia Malek Tells Family's History in Syria in New Book 'The Home That Was Our Country'

Christina Tkacik

The Baltimore Sun

It was the spring of 2011 when Alia Malek told her younger sister Rana the news: She was moving to Damascus. The Syrian uprising had just begun. People would be fleeing en masse. Yet Malek — a journalist, author and lawyer — would be flying in.

The prospect was worrisome. What if Malek was killed by a bomb? Or kidnapped, and held for ransom? The U.S. wasn’t paying ransoms.

But Malek, now 42, had made up her mind.

“I wanted to be there to witness it,” she said. And to write about it. Having spent her life on the margins of American life, she firmly believed that the people experiencing an event needed to be the ones writing about it.

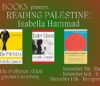

For her new memoir, “The Home That Was Our Country,” Malek, a Baltimore native, retraced her family’s roots to the Ottoman Empire, telling their story in the context of Syria’s tumultuous history. She’ll be speaking about the book on April 15 at Bird in Hand.

The memoir references the sense of charisma, or shakhsiyeh in Arabic, possessed by relatives such as her great-grandfather (“Abdeljawwad” in the book), her grandmother (“Salma”) or her own father.

It’s a trait she herself shares.

“She is the energy in a room when she’s in it,” said Rana Malek, a physician in Baltimore. When Rana has introduced her to longtime friends, “She will be with them for 10 minutes, and the next day she’ll say something to me like, ‘Did you know so-and-so did x, y and z?’ ‘No, I’ve known so-and-so five years. How did you find that out in 10 minutes?'”

Drawing out the locked-up past is a skill Malek has put to use first as a lawyer, and now as a journalist.

“I think her work is just brilliant,” said fellow writer Susan Muaddi Darraj, an Arab-American author who lives in Phoenix, Baltimore County. “She has the integrity of a journalist and the research skills of a journalist, and she combines that with the lyricism of a creative writer.”

Malek grew up in Baltimore and Towson, to Syrian parents who came to the U.S. in the ’70s. The children spoke in Arabic with their mother. They ate Arabic food and on weekends spent time with friends from the local Syrian church.

At school, it was different. In the 1980s, Syria wasn’t on anyone’s radar. In a speech last year Malek remembered a bully asking: “If you’re from Syria, does that mean you eat a lot of cereal?'” She brushed it off. “I felt bad for him. I was like, ‘That’s all you got?'”

She recalls perusing shops for personalized key chains, searching for her own name. There might be an Alex, or Alice, but “I could never find an ‘Alia.'”

Looking back, Malek sees she was informed by a feeling of apartness from a young age. Her parents recently came across an essay she wrote in the third grade —1982 — comparing the Israeli invasion of Lebanon to the Civil Rights movement in the United States. “So already back then I was kind of like connecting that there are people out there who are ‘other.'”

Malek attended the Johns Hopkins University and then Georgetown Law before becoming a trial lawyer with the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division. She eventually earned a master’s from the Columbia School of Journalism and, in 2010, published “A Country Called Amreeka,” telling the history of the United States through Arab-Americans.

“As a writer, I’m stepping back and I’m trying to actually change what it is that we know about a people as a way to maybe pre-empt the prejudice and discrimination,” she said. “I know what it was like to be Arab-American, and to have one concept and understanding of who Arabs were and then to sort of see what pop culture and the media and politicians told me Arabs were.”

Anne Barnard, Beirut bureau chief of The New York Times, recalls first encountering “A Country Called Amreeka.” ”It was a much-needed book in the years after 9/11, deeply personal but also deeply reported,” Barnard wrote in an email to The Sun. “Later I got to know her and her beautiful writing about Syria, which is the same way. Voices like hers, fully American and fully Arab, are needed even more today.”

In 2011, the time seemed right for a book Malek had long wanted to write: about her own family in Syria.

Malek moved to the center of Damascus, to her grandmother’s old apartment. Compared to war-ravaged Homs or Aleppo, Syria’s capital has remained relatively safe from bombardment. Yet there were threats. She could be kidnapped by rebels. Should Malek run afoul of the Assad regime, it could mean detention, or worse.

Amid these dangers, Malek researched, mining the memories of relatives and friends to verify family lore.

“The Home That Was Our Country” opens in a Syrian village where her great-grandfather was born a subject of the Ottoman Empire in 1889. Malek probes some of the complexities of “Abdeljawwad,” a wealthy landowner who gave money to help fund anti-French revolts after World War I. Were these nationalistic heroes, as her family had often claimed? Or opportunistic moneymakers? Both?

“You have to be willing to let go of the family story,” Malek said. At times that meant being open to historical interpretations that cast family heroes in a less favorable light. “I think readers can accept a nuanced reality.”

While she researched, she restored her grandmother’s home — a process she documents in the book, drawing parallels between the building and the nation at large. She devoured books: on the East German Stasi, on North Korea, trying to better understand the insidious impact of the Syrian state. She freelanced stories for outlets like The Nation — without a byline, since the Assad regime was monitoring journalists to control the flow of information from the country.

There were Skype calls back home, to family, to Rana. The sisters never talked about politics; a knack for self-censorship they learned as children and teens traveling to the country, alert to the secret police, or mukhabarat.

Lest she forget, in the book, Malek recalls the warning of her mother, who met her in Damascus in 2011: “Be careful what you say and keep your thoughts to yourself.”

There was one recurring question, said Rana: “When are you coming home?”

In 2013, Malek began to fear that her presence might endanger family members in Syria. A family member in the U.S. was ill. It was time to return.

Alia Malek’s great-grandmother (center of back row) with her children, around 1928. Malek’s grandmother is front row, middle. (Courtesy of Alia Malek/HANDOUT)

“The Home That Was Our Country” seems to ache for all that has been lost in the conflict, now six years running. But Malek shuns nostalgia. Of her childhood trips to Syria, she writes “My memories of our visits were sketched mostly in sensations: The smell of diesel, jasmine, and roasting coffee beans.” The image she creates is never too perfect.

She saves her harshest critique for the Assad regime, expounding on the lies and toxic impact of the state, its brutal suppression of dissent. The 2011 uprising, Malek writes, began after a group of boys scrawled revolutionary graffiti, and were then tortured by the regime, their bodies burned and their fingernails pulled out.

Malek isn’t afraid to air the proverbial dirty laundry for the world to see, said Mauddi Darraj.

“She’s like a bridge between these two worlds, and she writes about the region in a way that is helpful and explanatory, but not sentimental,” said Muaddi Darraj. “I really admire that as a writer.”

While she was on deadline to finish “The Home That Was Our Country” Malek also edited “Europa,” a guide for refugees and migrants headed for the continent. “(I)t felt like the convergence of everything I’ve been working on. I was in the middle of a book about Syria, so I was steeped in the context that gave rise to their migration.” And of course, she’d lived her own Syrian immigration experience in the United States.

Rana Malek picked up her sister’s book at Barnes & Noble a few days after it came out last month; it’s hard for her to read. There are chapters that detail dangers Rana didn’t realize Malek was in at the time. A woman Malek had interviewed, in the book known as “Carnations,” was arrested a day after she and Malek met. Relatives had spread rumors Malek was a spy, according to the book.

“Had any of us known, we would’ve gotten someone to put her in a FedEx box and send her back to us,” Rana said.

But Malek is quick to point out that she had a document that made her safer than the average Syrian: a U.S. passport.

Still, “I would go back in a heartbeat. I don’t know if I’m welcome.” Should it catch the attention of the Assad regime, her new book may sever her even more from the country she once called home.