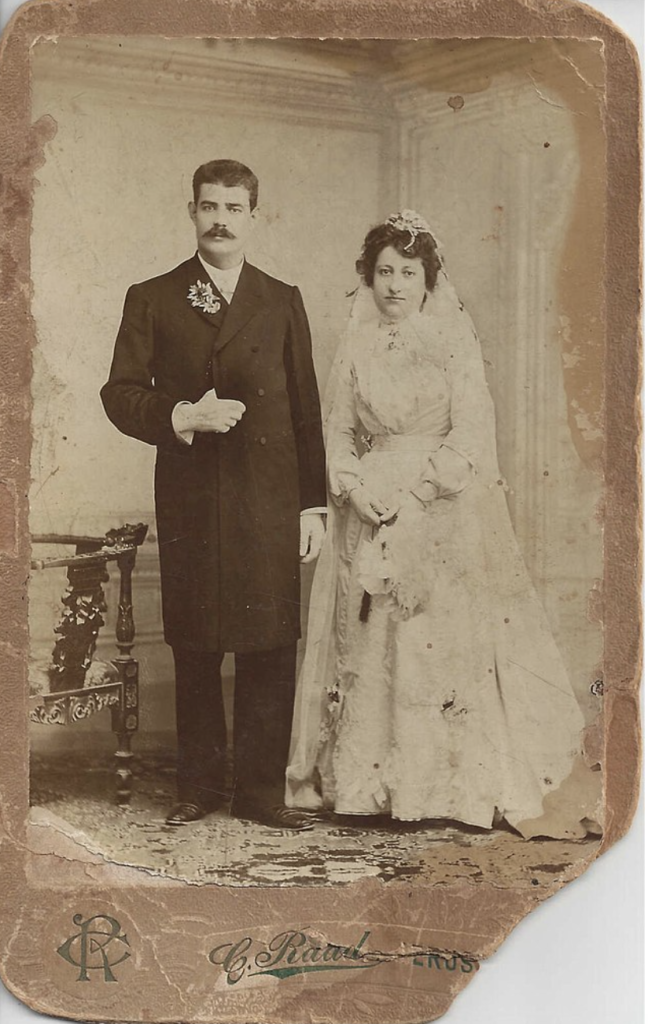

A Glimpse into 19th-Century Syrian Christian Weddings

By: Arwa Almasaari / Arab America Contributing Writer

Weddings are more than just ceremonies—they are monumental events in one’s life. Have you ever wondered how Arabs celebrated their weddings in the nineteenth century? In his autobiography, A Far Journey, Abraham Rihbany provides a unique and detailed firsthand account of Syrian Christian weddings in Greater Syria. Through detailed descriptions, Rihbany brings to life the customs and traditions that make these ceremonies memorable.

Abraham Rihbany, born in 1869, emigrated to the United States in 1891. His autobiography, published in 1914, details daily life in his birthplace, El Shweir (Dhour El Choueir/Dhour Shweir), and the town of Betater (Btater). Over six pages, Rihbany provides an in-depth portrayal of his relatives’ wedding ceremonies. He emphasizes that in nineteenth-century Syrian Christian culture, weddings hold unparalleled significance, with marriage seen as one of the most crucial milestones in a person’s life.

A Day of Unparalleled Significance

Rihbany asserts that marriage is more than a sacred ceremony for Syrians; it represents the highest ideal. He notes that the greatest compliment a guest can offer at the end of a meal is, “May we eat again within this house at the wedding of the dear grooms [i.e., sons].” From a young age, boys are reminded of this ideal, and any service they provide is often met with, “May we serve at your wedding.”

Guests arrive in large groups, often numbering “hundreds and fifties,” representing various clans and households. As they approach the bridegroom’s house, they begin singing in separate groups, each with its own melody. A large group from the groom’s family rushes out to welcome them with cheerful songs and joyful shouts. When the two groups merge, their combined voices create a loud, chaotic “joyful noise” that transforms into a thunderous roar. The guests are welcomed inside the house with the same enthusiasm.

Once inside, the singing subsides, and the bridegroom’s relatives form a straight line with him at the center, facing their guests, who also line up. In unison, the guests offer their blessings: “Blessed, O bridegroom, be your enterprise; May Allah bless you with many sons and a long life; Our joy this day is supreme.” The bridegroom’s relatives then respond: “May Allah bless your lives; May such events happen in your homes; May all your sons who are needy [of marriage] be so blessed and made happy. You have honored us by your coming!” Rihbany finds this part of the wedding the “most thrilling,” as it conveys a powerful sense of strength and beauty.

The Bridal Procession

Sunday marks the final and most significant day of the wedding celebrations, as the marriage is officially formalized. The entire town gathers for this grand occasion. If the ceremony is held at the bridegroom’s house, the bride is brought there, much like how “Rebekah was brought to Isaac’s house.” If the ceremony takes place at the church, which is more common, both the bride and groom are escorted by large groups.

Bride and Groom Performance

Rihbany recalls, as a child, being captivated by “the bringing of the bride” from her father’s house. In this event, selected men are sent to “bring the bride,” reflecting an ancient custom where strong men would forcefully take the bride from her family. Throughout the festivities, the bridegroom maintains a solemn demeanor while the bride refrains from speaking. She is trained to keep her eyes gently closed, opening them only occasionally, with her eyelids drooping gracefully, just barely touching the fringes. These “drooping eyelids” are often celebrated in poetry as symbols of a bride’s bewitching loveliness.

Rihbany was also puzzled by the sudden transformation in the bridegroom and bride during the wedding. How did they suddenly acquire such unapproachable dignity? He was amazed when, just a few days after the wedding, he saw them behaving like ordinary people again. The bridegroom no longer appeared awe-inspiring, and the bride’s eyes were wide open as she spoke freely.

After the escorting party arrives and is served wine and confections, Rihbany notes that the bride is slowly led from her seat by the women attendants and the bridegroom’s closest male friends. Following tradition, she takes her time leaving her father’s house, with the walk to the door sometimes taking up to half an hour. At the door, strong men lift her onto a decorated horse or mule while another mule carries her belongings. The procession then slowly moves toward the sanctuary amid joyful celebrations, with a large crowd accompanying the bridegroom.

Nighttime Splendor

When the ceremony is held at night, it turns into a stunning spectacle. Sword players, singers, musicians, torchbearers, and other entertainers surround the bridegroom and join the procession. Spectators on rooftops, mostly women and children, shower the crowd with rose water, flower water, wheat (symbolizing fertility), and confections. Waves of zelagheet (zagharit/ululation) float over the crowd. The procession continues with flashing swords, flaring lamps, and a lively din of music and song while the call, “Behold the bridegroom cometh! Go ye out to meet him,” rings out.

At the altar, the bride and groom are united in a moving ceremony. Afterward, the crowd accompanies the couple to the bridegroom’s house for a grand feast. An abundant feast is provided for all, with guests from every walk of life filling the house to its capacity. During the summer, the feast is often held on the rooftop. In winter, when most weddings occur, guests crowd indoors to enjoy the warm “Syrian hospitality.” The festivities end with this grand feast.

Reference:

Rihbany, Abraham Mitrie. A Far Journey. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914.

Arwa Almasaari is a scholar, writer, and editor with a Ph.D. in English, specializing in Arab American studies. She often writes about inspirational figures, children’s literature, and celebrating diversity. You can contact her at arwa_phd@outlook.com

Check out our blog here!