A Day, a Life: When a Medic Was Killed in Gaza, Was It an Accident?

SOURCE: THE NEW YORK TIMES

BY: DAVID M. HALBFINGER

KHUZAA, Gaza Strip — A young medic in a head scarf runs into danger, her only protection a white lab coat. Through a haze of tear gas and black smoke, she tries to reach a man sprawled on the ground along the Gaza border. Israeli soldiers, their weapons leveled, watch warily from the other side.

Minutes later, a rifle shot rips through the din, and the Israeli-Palestinian drama has its newest tragic figure.

For a few days in June, the world took notice of the death of 20-year-old Rouzan al-Najjar, killed while treating the wounded at protests against Israel’s blockade of the Gaza Strip. Even as she was buried, she became a symbol of the conflict, with both sides staking out competing and mutually exclusive narratives.

To the Palestinians, she was an innocent martyr killed in cold blood, an example of Israel’s disregard for Palestinian life. To the Israelis, she was part of a violent protest aimed at destroying their country, to which lethal force is a legitimate response as a last resort.

Palestinian witnesses embellished their initial accounts, saying she was shot while raising her hands in the air. The Israeli military tweeted a tendentiously edited video that made it sound like she was offering herself as a human shield for terrorists.

In each version, Ms. Najjar was little more than a cardboard cutout.

An investigation by The New York Times found that Ms. Najjar, and what happened on the evening of June 1, were far more complicated than either narrative allowed. Charismatic and committed, she defied the expectations of both sides. Her death was a poignant illustration of the cost of Israel’s use of battlefield weapons to control the protests, a policy that has taken the lives of nearly 200 Palestinians.

It also shows how each side is locked into a seemingly unending and insolvable cycle of violence. The Palestinians trying to tear down the fence are risking their lives to make a point, knowing that the protests amount to little more than a public relations stunt for Hamas, the militant movement that rules Gaza. And Israel, the far stronger party, continues to focus on containment rather than finding a solution.

In life, Ms. Najjar was a natural leader whose uncommon bravery struck some peers as foolhardy. She was a capable young medic, but one who was largely self-taught and lied about her lack of education. She was a feminist, by Gaza standards, shattering traditional gender rules, but also a daughter who doted on her father, was particular about her appearance and was slowly assembling a trousseau. She inspired others with her outward jauntiness, while privately she was consumed with dread in her final days.

The bullet that killed her, The Times found, was fired by an Israeli sniper into a crowd that included white-coated medics in plain view. A detailed reconstruction, stitched together from hundreds of crowd-sourced videos and photographs, shows that neither the medics nor anyone around them posed any apparent threat of violence to Israeli personnel. Though Israel later admitted her killing was unintentional, the shooting appears to have been reckless at best, and possibly a war crime, for which no one has yet been punished.

3:45 a.m., Friday, June 1

The last day of her life begins well before sunrise. Ms. Najjar fries sambousek, small meat pies, to share with her father for the predawn meal before the Ramadan fast. She shows him a new suit she bought for her 5-year-old brother, Amir. They pray together before going back to sleep.

When he awakens that afternoon, she is gone.

Just around the corner from the Najjar home in Khuzaa, visible from their rooftop, is a barren field that has been turned into the stage for one of five protests along the Gaza-Israel border fence. Nearly every day for the past nine weeks, hundreds of Palestinians have flocked here for demonstrations. On Fridays, there can be thousands. The protests often culminate in rocks or firebombs thrown at the Israeli side, and Israeli tear gas and gunfire in response. The protesters’ stated goal is to break through the fence and return to their ancestral homes in what is now Israel. But the immediate focus is the 11-year-old Israeli blockade of Gaza. The blockade, which is also enforced by Egypt along Gaza’s southern border, has choked Gaza’s economy and left its 2 million residents feeling imprisoned.

Today, the medics are hoping for a low-key Friday. But around 5 p.m., the protest gains energy. A crowd surges toward the fence and the Israelis unleash a suffocating barrage of tear gas.

There has been no gunfire yet. It is still possible to kid around. “Let’s go get martyred together,” Ms. Najjar teases Mahmoud Abdelaty, a fellow medic. “Go on and get hit so I can take care of you.”

“Are you scared of death?” she asks Mahmoud Qedayeh, another member of their team of volunteers. “You only die once.”

‘Everybody Knew Her’

For the Israel Defense Forces, she was a nightmare of a victim: a photogenic symbol of nationhood, youth and compassion.

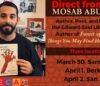

On March 30, the protests’ first day, Ms. Najjar became the youngest of three volunteers tending to the wounded, and the only woman.

To the young men in skinny jeans and T-shirts hurling rocks at Israeli soldiers, she seemed to appear beside them almost as fast as they fell, bandaging burns, splinting fractures, stanching gunshot wounds, offering encouragement, sometimes hearing last words.

Journalists noticed. Practically overnight, she became a fixture of news reports, with a growing social-media following. “Everybody knew her,” said another medic, Lamiaa Abu Moustafa.

Over the next nine weeks, shrapnel pelted Ms. Najjar’s legs, a flaming tire burned her, a tear-gas grenade fractured her arm. She cut off her cast the same day and went back to the protest.

Others cowered when Israeli soldiers fired at them. Not Ms. Najjar. “The gunshots we hear will not harm us,” she told a colleague. The implication: You won’t hear the one that kills you.

She inspired other women to become medics, despite social conventions in this deeply conservative Muslim territory that reserve dangerous work for men. “I wanted to become like Rouzan, brave and strong and helping everybody,” said Najwa Abu Abdo, a 17-year-old neighbor, explaining her decision to volunteer.

Unmarried and uninterested in marriage for the time being, Ms. Najjar remained very much the star of her own drama. She sent affectionate texts to peers who each believed they were her closest friend. She lied about her credentials, pretending to be a college student. She obsessed over backbiting and jealousy within her social circle.

Yet she had more on her mind.

For Ms. Najjar, the protests were not just an opportunity to vent at the barbed wire that made Gaza feel like an open-air cage. They were an opportunity to gain medical experience, to make a name for herself and perhaps, by making an impression, to further her goal of making nursing school affordable.

By late May, she seemed well on her way.

5:30 p.m.

Tear gas is everywhere. The Israelis have not yet fired live ammunition, but the acrid fumes are overwhelming. “Like a dense fog,” says Fares al-Qedra, another medic.

It’s a giant dance: Protesters run toward the fence, soldiers launch gas grenades, the protesters back off. Repeat.

Ms. Najjar, noticeable in her white coat and red lipstick, scurries around spraying saline solution in people’s eyes to wash away the gas. So many need her help that she cannot keep up.

A 54-year-old man is hit in the forehead by a gas grenade. Ms. Najjar rushes to him, bandages the gash, then runs alongside as he is carried to an ambulance.

A Flimsy Fence

Gaza had not always been locked up behind barbed wire, sensors and bunkers.

Before 2005, Gaza residents could work in Israel. But rocket attacks and bombings after the Second Intifada erupted in 2000 prompted Israel to cordon off the strip and eventually abandon its settlements there. When Hamas seized power from the Palestinian Authority after a weeklong civil war in 2007, Israel imposed a punishing blockade, severely restricting travel and trade.

By 2017, after three wars with Israel, Gaza’s economy was a shambles and the authority’s president, Mahmoud Abbas, was determined to finish off Hamas. He laid off thousands of Gaza workers and cut electricity to a few hours at a time.

Just as support for Hamas was cratering, young Gazans called for a mass protest against the blockade. Hamas jumped at the chance to redirect popular anger against Israel. Officials promised nonviolence but nonetheless encouraged protesters to try to break through the fence.

With imams urging people to attend and Hamas chartering buses, crowds grew quickly. The protests became a kind of nationalist circus. Mothers brought children, vendors hawked falafel and families slept in tents. Nearer the fence, young men burned tires, crept up with wire cutters or improvised firebombs — and presented Israeli snipers with easy targets.

Bloodshed served Hamas’s public-relations purposes, winning international attention and sympathy. The Israelis obliged.

For Israel, the protests touched a nerve: The border was demarcated by a fence, not a wall — a relatively flimsy contraption designed to detect intrusion, not prevent it. Technically, it was not even a recognized border, only the armistice line drawn in 1949, after the Israeli-Arab war.

Fearing an onrush of thousands, the army warned Gaza residents that anyone coming close to the fence would be shot.

Later, Israeli officials explained that military policy permitted deadly force only as a last resort, against an imminent threat of violence, and after exhausting lesser options like verbal warnings, tear gas and warning shots. Spokesmen insisted that commanders had to approve each shot and, in one subsequently deleted Twitter post, that “We know where every bullet landed.”

But the first day of protests alone left more than 20 dead and hundreds wounded. Since then, one Israeli soldier has been killed by sniper fire. The Palestinian death toll has reached 185.

The victims include two women and 32 children. Journalists. A double-amputee in a wheelchair. A young man who had a tire in his arms and was running away from the fence when he was shot in the back.

And medics.

6:13 p.m.

A new friction point has opened up: A few dozen protesters have drifted about 200 yards north along the fence, past the point where a bunker on the Israeli side had loosely marked the protest’s northern boundary.

Some of the protesters begin tearing at the barbed-wire coils about 40 yards in front of the fence.

Israeli soldiers quickly drive up and take defensive positions on the other side. They’ve shot people for less. For now, they fire only a warning shot and more tear gas.

Like a Prisoner

Except for a visit to Egypt in 1997, at three days old, Ms. Najjar spent her life confined to the cramped Gaza Strip, mainly in Khuzaa, a tiny border village where nearly everyone is a Najjar — descended from refugees who fled in 1948 from Salamah, near Jaffa.

Rouzan was precocious, entering kindergarten at 2, picking up English words and reciting poetry. And happy: Her mother, Sabreen, given to melancholy, recorded her laughing. “She would move worlds when she saw me sad,” she said.

But Rouzan was a daddy’s girl. Her father, a lanky entrepreneur named Ashraf al-Najjar, spoiled her, when that was still possible. He worked in Israel for months at a stretch, buying appliances or furniture to sell in Gaza at four times what he paid. There was meat for dinner.

“To be honest, I long for those days,” he said.

As a little girl, Rouzan reached for toy stethoscopes. Her father expected to send her overseas to study medicine someday.

But then came the rockets, the blockade, the wars. No longer able to work in Israel, Mr. Najjar opened a motorcycle-repair shop. It was bulldozed by the Israeli army during the 2014 invasion. He went bankrupt and took handouts from siblings. Rouzan skipped school field trips to scrimp.

Khuzaa was largely reduced to rubble in the war. Two of Rouzan’s best friends were killed, one of them along with more than 20 of her relatives. She saw a cousin’s body torn apart. The Najjars’ home was damaged, the recordings of her laughter lost. When they returned from shelter, the dead and dying lay in the streets.

Rouzan said she wanted to learn how to help.

Opposite the Israeli bunker, Ms. Najjar rushes toward the fence to help a teenager, as Israeli soldiers look on. Someone behind her throws a rock at them, using her as cover.

Two protesters are trapped near the barbed wire, lying on the ground.

She and several other medics — among them her friends Rasha Qudeih and Rami Abo Jazar — make their way forward again to try to help. They raise their hands to show the Israelis they mean no harm.

Two shots ring out overhead. Ms. Najjar waves at the soldiers, who are only about 50 yards away, not to shoot. But as she edges closer, another shot, much closer, kicks up the sand.

A soldier emerges from behind a jeep, leveling his rifle. “The sniper is aiming at us!” Ms. Qudeih yells.

The medics turn and run, as a fresh barrage of tear gas descends on them. Ms. Najjar is the slowest to retreat.

Fearless at 15

Nearly everyone who saw Ms. Najjar at the protests was struck by her readiness to place herself in harm’s way. Again and again, there she was in video clips: the first to those in trouble, the last to safety.

“She was reckless,” said Eslam Okal, a trauma nurse from Rafah who volunteered at the Khuzaa protests after hearing about Ms. Najjar. “I told her, ‘Your first priority is safety.’ We had many arguments over this. But her bravery won out.”

In high school, she was the alpha of a clique of mildly rebellious teenagers who bridled at the dress code of their all-girls school: white scarf and hijab, dark trousers. Ms. Najjar wore bright colors and accepted the scoldings that followed.

Other girls were quiet in class. But Ms. Najjar interrupted the teachers with questions, stood her ground when chastised and talked back constantly, though usually through a smile.

How she became so fearless and outspoken is impossible to pin down, but several people who were close to her cited a traumatic experience when she was 15.

During 10th-grade finals, Rouzan returned home to a tense situation in her family’s four-story building. Her aunt, Nawal Qedayeh, whom Rouzan adored and who was seven months pregnant, was being treated like a pariah by Rouzan’s paternal aunts and grandmother, who refused to let her use the communal kitchen. When Ms. Qedayeh was caught scrubbing pots there, a fight broke out, and Rouzan watched as her grandmother pushed Ms. Qedayeh down the stairs. Both she and the fetus she was carrying were killed.

Rouzan, the only eyewitness, had a choice: She could stay silent, forgoing justice for her aunt’s killing and following the social expectation for a young woman to leave weighty legal matters to the men. Or she could tell the truth and potentially send her grandmother to prison.

Rouzan testified. Her grandmother was convicted of accidental manslaughter and spent more than a year in prison.

Nisreen Abu Ishaq, Rouzan’s high school religion teacher, said the ordeal made her “stronger and more daring.” After that, said Suzan Mahdi al-Reqeb, a school administrator, “nothing stood in her way.”

Money did. Knowing she couldn’t afford college dejected her. She had also failed part of the entrance exams. Yet she scarcely gave up.

“On the contrary,” her mother said. “She stomped her feet and said, ‘I’m not going to waste years waiting for things to get better — I’ll find another way.’”

She began taking basic first aid courses and discovered that she could simply “forget” to pay the fees: “Don’t be an idiot,” she told a friend who almost paid $5 in tuition.

She hung around emergency rooms, running errands, observing surgery, pretending to belong until the staff realized she didn’t. When Seif Abdel Ghafour rushed his dying uncle to Nasser Hospital, he was bewildered by the place until Ms. Najjar led them where they needed to go. “She didn’t know us,” he said. “But she treated us like we were her brothers.”

The protests would let her test her skills. When the Health Ministry made about 200 volunteer medics take a written exam, Ms. Najjar scored 91, the highest in her group. She was given an identification card, lab coat and white-and-pink paramedic’s vest.

She wore them like armor.

6:20 p.m.

To the north, past the bunker, at least two protesters throw homemade firebombs at the Israelis. No damage is done, but it’s a significant escalation from slinging rocks.

Ms. Najjar is recovering from the tear gas she inhaled. Nearby, protesters start cutting away a new section of barbed wire.

Suddenly, there’s a rifle shot. A young man in the group to the north is hit in the leg.

That is where Israeli forces are instructed to aim, a tactic, Israeli officials say, intended to minimize fatalities. But they fire a heavy battlefield round, one meant for targets hundreds of yards away. At 100 yards, ballistics experts say, a missed shot could bounce like a skimming stone.

“If I missed, and it will hit a rock, I don’t know where the bullet will go,” a senior Israeli commander says.

‘A Daughter of Men’

Nearly every protester in Khuzaa has at least one story of Ms. Najjar coming to his rescue. Some have many.

When Mahmoud Abu Shab, 26, a kafiyeh-wearing rock thrower, was shot through the hand in March, she stanched the bleeding. One day in April, when he failed to get out of the way of a stretch of barbed wire being dragged from the fence, she bandaged his wounds.

He didn’t know that she had bought the medical supplies herself. She was collecting a shekel a day from a group of supportive young women. She even sold off a gold ring to buy supplies.

“She wanted to always be at the fence, to be a daughter of men,” said Nada al-Laham, another volunteer, using an expression for a woman driven by a strong sense of national identity.

Her father said he urged her to take a day off: “She’d say, ‘No, Baba, there are people who need me.’”

Her mother visited the protests, but said their chats ended abruptly: “Suddenly there would be a wounded protester, and she’d just stop talking and say, ‘I have to go, there’s someone I need to save.’”

Ms. Najjar saw her role as part of the Palestinian struggle as much as those burning tires or wielding wire cutters. She became a practiced spokeswoman, never refusing an interview request, not always waiting to be asked.

“We want to send our message to the world: I’m an army to myself, and the sword to my army,” she told The Times on May 7. “We have one goal, and that’s to rescue and evacuate, and to send a message to the world, that we — without weapons — we can do anything.”

Her Facebook posts could be florid. She once wrote that her bloodstained uniform carried the “sweetest perfume.”

The protests became Gaza’s biggest social event. Matches were made, engagements announced almost every day. Young men and their parents paraded through the Najjars’ home seeking betrothal to the now-famous Rouzan. “Ten or 12 just during Ramadan,” her father said.

She turned them all down, he said: “She had her own goals in mind.”

After the protests ended, she planned to retake and ace the college-admission tests. Somehow, she would find her way to nursing school.

6:29 p.m.

Ms. Najjar is back on her feet beside her colleague, Ms. Abu Moustafa, her closest friend among the medics. Protesters tugging at the barbed wire scramble by them toward the south, hoisting their long rope over the women’s heads.

Ms. Abu Moustafa is concerned. The Israelis often shoot at the rope pullers, she says. She urges Ms. Najjar to leave.

The rope pullers finally make off with a small coil of barbed wire. Much of the crowd follows. The clamor around the two women subsides.

Air of Mortality

As the protests took on a sense of permanence, Ms. Najjar’s bravado became alloyed with increasingly frequent allusions to her possible demise.

“When my life finishes, make me a sweet memory for those who know me,” she wrote on Facebook on May 5.

“They said to me, ‘Bend a little, as the bullet is on its way to you,’” she wrote later. “I said to them, ‘The bullet chose me because I do not know how to bend, so why should I change my way?’”

She texted one friend an apology in case one of them was martyred.

“Say a nice prayer for my memory,” she told another on May 24.

Her parents said such morbid talk was uncharacteristic. While many in Gaza speak of death as preferable to the here-and-now, Ms. Najjar “clung to life,” her mother said. “She never wanted to be a martyr. She loved life.”

One of her happiest days ever, friends said, was Tuesday, May 29. She cashed a $100 check — a one-time gift to each member of her team of medics, the Palestine Medical Rescue Service, from its overseers in the West Bank — and joined colleagues on a small boat that left the Gaza City marina, hoping to catch up to a flotilla that was challenging the blockade.

They were on the water nearly three hours under the brilliant Mediterranean sun before being turned back by an Israeli gunboat.

“I said I hoped we wouldn’t get hit,” said Mr. Abdel Ghafour, the man she had helped at the hospital and who had since befriended her. “She said, ‘So be it! We die as friends.’”

6:31 p.m.

Sunset is coming and with it, the end of the fast. Things seem to be quieting down at the fence.

An Israeli soldier looking across at where Ms. Najjar stands now might see a man waving a Palestinian flag aloft, a few straggling protesters ambling around, and a cluster of medics helping a protester on the ground recover from tear gas. No one in the area is doing anything menacing. The tear gas is doing what it is meant to: making the use of lethal force unnecessary.

Suddenly, there is another gunshot.

Mohammed Shafee, a medic, sees things “fly into my body.” He’s sprayed in the chest by small bullet fragments.

Mr. Abo Jazar perceives an explosion on the ground, then screams in pain. He’s grazed in the thigh.

Behind them, Ms. Najjar reaches for her back, then crumples.

As Ms. Abu Moustafa looks on in shock, Ms. Najjar is picked up by protesters she had treated just a few minutes ago. As they carry her off, blood pours from her chest.

To Shoot or Not to Shoot

Three medics down, all from one bullet. It seemed improbable.

But The Times’s reconstruction confirmed it: The bullet hit the ground in front of the medics, then fragmented, part of it ricocheting upward and piercing Ms. Najjar’s chest.

It was fired from a sand berm used by Israeli snipers at least 120 yards from where the medics fell.

The Israeli military’s rules of engagement are classified. But a spokesman, Lt. Col. Jonathan Conricus, said that snipers may shoot only at people posing a violent threat, like “cutting the fence, throwing grenades.”

To deliberately shoot a medic, or any civilian, is a war crime. Israel quickly conceded that Ms. Najjar’s killing was unintended.

“She was not the target,” Colonel Conricus said. “None of the medical personnel are ever a target.”

But no Israeli soldiers reported accidental shootings. After-action reports said snipers aimed at four men that day and hit them all, the army said.

The Times found the first, third and fourth of those protesters, each shot in the leg exactly when and how the army said they were. But The Times could not corroborate the army’s description of the second person it said was shot, which matched the time Ms. Najjar was killed.

The army said it was a man in a yellow shirt who was throwing stones and pulling at the fence. But the only man in a yellow shirt anywhere near the line of fire was not doing that or much of anything else, The Times found. He stood about 120 yards from the fence and posed no threat.

Even if the man was a legitimate target, there remains the question of the medics standing behind him.

Former Israeli and American snipers said it would be reckless to shoot if anyone who was not a legitimate target could be put at risk. Reckless killing can also be a war crime.

Prof. Ryan Goodman, a New York University expert on the laws of war, who was a special counsel to the Pentagon on war crimes and targeting rules, said the key to whether a war crime was committed was whether the sniper was aware of a high risk that civilians would be harmed.

“The laws of war would not want any military personnel to deliberately fire in the direction of the medics,” Mr. Goodman said. “I’m not saying it’s close to the line. I’m saying it crosses the line.”

Mistakes Add Up

A senior Israeli commander told The Times in August that 60 to 70 other Gaza protesters had been killed unintentionally, around half the total killed at that point.

Yet the Israeli army’s rules of engagement remain unchanged, the military says.

That alone may constitute a separate violation of international humanitarian law, experts say: After enough civilians have died, commanders have a duty to make changes to ensure that they aren’t needlessly targeted.

“You lose the right to say, ‘Oops,’” said Noam Lubell, a professor of the law of armed conflict at the University of Essex.

The large number of accidental killings, and Israel’s failure to adjust the rules of engagement in response, raise the question of whether they were a bug or a feature of its policy.

Colonel Conricus said that not all those killed unintentionally had been shot unintentionally. Sometimes soldiers had aimed at the legs of people they considered to be legitimate targets, he said, but killed them instead of wounding them.

Israel considers members of Hamas fair game whether they are armed or not, an interpretation of international law that is not universally accepted.

Colonel Conricus also said the rules of engagement were merely an upper limit on the use of force, and that the army was doing other things, such as training troops when they are first assigned to the fence, to curb civilian casualties.

Israeli military lawyers conceded there had been some misconduct but said that no soldiers were suspected of intentionally killing anyone they knew they shouldn’t have.

On Oct. 29, nearly five months after she was killed, Israel’s military advocate general began a criminal investigation of Ms. Najjar’s death.

But the senior commander told The Times in August that no recordings of the shooting from the Israeli side existed. He had no idea exactly when Ms. Najjar had been shot. He learned that from The Times.

Israel seems content to say that protecting its border is a messy business. “Unfortunately, yes,” said Colonel Conricus, “in a situation like that, accidents happen, and unintended results happen.”

6:37 p.m.

An ambulance races Ms. Najjar to a triage tent, where she is deposited in the “red zone” for trauma cases.

She had wanted so badly to belong here that she used to visit the tent often, even when she was not escorting patients. Now, the professionals crowd around frantically trying to save her. The doctor who intubates her is the same one who administered the Health Ministry exam she aced back in April.

Three people record the scene on smartphones, a reminder of her celebrity.

Ms. Najjar takes her last breath even before she is rushed to a nearby hospital, where she is pronounced dead at 7:10 p.m.

“Why kill her?” cries her shattered father. “She was an angel of mercy.”

Ms. Najjar has joined the ranks of those lionized as Gaza’s martyrs. Her smiling portrait will beam from walls and billboards across the territory. She has become a symbol, perhaps not of what either side had hoped, but of a hopeless, endless conflict and the lives it wastes.

Reporting was contributed by Yousur Al-Hlou, Malachy Browne, Iyad Abuheweila and Neil Collier from Khuzaa; Ibrahim El-Mughrabi from Gaza City, and John Woo from New York.