Celebrating National Baklawa Day

By Mehdi El Merini / Arab America Contributing Writer

Celebrated annually on November 17, national Baklawa Day honors one of the world’s most beloved pastries. Baklawa’s delicate, flaky layers and rich filling of nuts, sweet syrup, and fragrant rose water make it a dessert treasured across cultures. Although commonly associated with Turkish and Greek cuisine today, baklawa’s origins can be traced back to the medieval Arab world. This beloved dessert is more than just a treat—it’s a testament to the culinary artistry and cultural heritage of the Arab world, whose methods and flavors influenced how this dessert is made and enjoyed today.

The Origins of Baklawa in Medieval Arab Cuisine

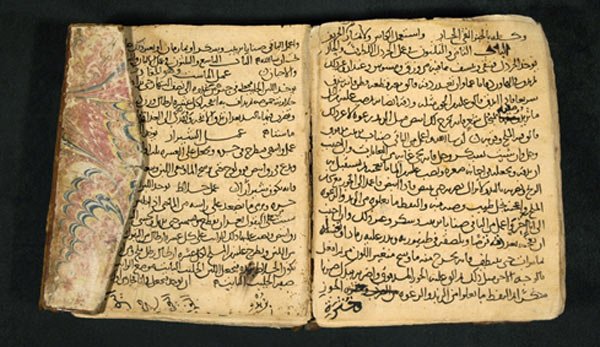

Baklawa’s exact origins are still being debated today, with claims emerging from both Greek and Ottoman history. However, it appears that its early roots lie in the ninth century, during the Islamic Golden Age, when culinary experimentation and refinement flourished. References to an early form of baklawa can be found in ancient Arabic texts, particularly in the Kitaab Al-Tabikh, or “The Book of Dishes,” written by the ninth-century scribe Ibn Sayyar Al-Warraq. One of the recipes described a pastry known as “kunafa,” but this was far from the kunafa widely known today. Instead, kunafa referred to the paper-thin dough sheets stuffed with or topped with nuts, sugar, and fragrant rose water. This kunafa, in texture and ingredients, was a predecessor of modern baklawa, showcasing how Arabs were already experimenting with thin dough sheets and sweet, nut-filled layers.

The Art of Making Kunafa Dough: The Foundation of Baklawa

Medieval Arab bakers were skilled in the intricate art of dough-making, creating exceptionally thin layers known as “yufka” or “warqa” in Arabic, meaning paper-thin sheets. The meticulous process involved kneading, stretching, and shaping the dough into almost transparent layers, a technique that required patience and mastery. The term “kunafa” described not the cheese-filled dessert popular today, but rather these thin, delicate sheets of dough. These sheets were then layered and stuffed with a blend of chopped nuts, spices, sugar, and rose water to create a delightful harmony of textures and flavors.

Arab bakers would often dust their dough with finely chopped almonds or pistachios, sweetened with honey or sugar syrup, and add a hint of rose or orange blossom water. The final result was both fragrant and flavorful, capturing the essence of Arab desserts: a careful balance of richness and sweetness, with a light floral undertone. These early iterations of this dessert were typically reserved for special occasions, symbolizing hospitality, generosity, and abundance.

An Umayyad Caliph’s Passion for Kunafa

The popularity of kunafa (baklawa dough) as a luxury dessert is evident in historical accounts, including stories involving Umayyad Caliphs who indulged in this sweet treat. One of the caliphs, particularly known for his fondness for kunafa, reportedly consumed it in such quantities that it became legendary. According to various historical sources, he would sometimes eat entire platters of kunafa in a single sitting, reveling in its rich texture and sweetness. His enthusiasm helped elevate kunafa’s status in the royal courts, encouraging bakers to refine their techniques and create increasingly elaborate versions of the dish.

This royal endorsement made kunafa and its variations popular among the elite, and it soon spread throughout the Arab Empire. Bakers in cities like Damascus, Baghdad, and Cairo began crafting their own versions, incorporating local flavors and ingredients. The art of creating paper-thin dough sheets with decadent fillings became a culinary standard, inspiring bakers across the region and setting the foundation for baklawa as we know it.

Potential Greek and Turkish Contributions to Baklawa

While baklawa has strong roots in Arab culinary history, it is also essential to acknowledge the contributions of both Turkish and Greek cultures to its evolution. As the Ottoman Empire expanded into the Eastern Mediterranean and the Balkans, they encountered and adopted many local culinary techniques, including desserts like baklawa. In Turkey, the dessert became a staple in Ottoman palaces, where bakers perfected layering techniques, experimenting with pistachios and other local ingredients, to create intricate, multi-layered pastries. Turkish chefs also made baklawa more widely accessible, spreading its popularity throughout the empire and, eventually, to Europe.

Greek baklawa, meanwhile, reflects its own regional nuances. Greeks commonly use honey in place of rose water, providing a unique depth of sweetness. Greek versions of baklawa also incorporate walnuts, adding a heartier flavor and texture to the dessert. In Greece, baklawa is typically associated with special occasions and religious celebrations, where it serves as a symbol of tradition and community. Greek baklawa often includes cinnamon and cloves, giving it a distinctive taste that contrasts with the floral notes of Arab baklawa.

These Greek and Turkish influences have led to distinct variations that enrich the tapestry of baklawa’s history. While each culture claims a unique relationship with baklawa, the shared enjoyment of this dessert illustrates the interconnectedness of the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern culinary landscapes. These adaptations, rather than detracting from baklawa’s origins, highlight the enduring appeal and adaptability of a dessert that transcends borders.

How Baklawa Became a Symbol of Arab Heritage

The spread of Arab culinary traditions across the Mediterranean and Central Asia introduced baklawa to various cultures. When the Seljuk and later Ottoman empires expanded, they encountered Arab desserts like kunafa, and these early forms of baklawa were adopted and adapted by Turkish chefs. Over time, the term “baklawa” itself became associated with this dessert, reflecting linguistic and culinary exchanges across empires. Although the Ottomans are often credited with popularizing baklawa in Europe and beyond, the early Arab influence on the dish’s development is undeniable.

By the 16th century, baklawa had become a common dessert in Ottoman palaces, with specialized bakers in Constantinople creating multiple layers of yufka dough and using local Turkish ingredients like pistachios and walnuts. The Ottomans refined and popularized the dessert, leading to its association with Turkish cuisine. However, the essence of baklawa—the thin, buttery layers filled with nuts and infused with floral syrups—remains deeply rooted in Arab culinary heritage.

Modern Baklawa: A Shared Delight with Ancient Roots

Today, baklawa is enjoyed across the Arab world, from Lebanon and Syria to Morocco and Egypt, each region adding its unique twist to the recipe. Arab baklawa tends to be lighter, often using fewer layers of dough and more fragrant syrups made from rose water or orange blossom. This variation reflects the historical Arab preference for subtle sweetness and delicate flavors, honoring the dessert’s roots in medieval Arab cuisine.

International Baklawa Day celebrates the global appeal of this dessert, inviting people from different backgrounds to appreciate the shared heritage behind this dessert. While it has traveled far from its origins, baklawa’s journey from medieval Arab kitchens to the world’s tables is a reminder of the cultural exchanges that have enriched our culinary traditions.

As you indulge in a piece of baklawa this national Baklawa Day, take a moment to savor not only its taste but also its rich history—a sweet legacy that continues to connect cultures and generations through the universal love of good food.

Check out our blog here!